When you examine the scene below, what do you see?

One of the pleasures of looking at old postcard views, such as this one printed for the druggist A.B. Petrie & Son, is they can be enjoyed in many ways. They can be enjoyed simply for their aesthetic value. They can be enjoyed for the glimpses that they afford into the people and things depicted in them. They can also be enjoyed as puzzles, challenging viewers to figure out what is happening and when. What you see depends on what you are looking for.

Of course, the image in the postcard above is of St. George's Square, an image that was reproduced in several Edwardian postcards and that I have discussed in a previous post.

In aesthetic terms, the image is nicely layered. In the foreground is a woman with a parasoal strolling away from the camera, off on some unknown errand. In the middle ground is a two-wheeled cart. Although such an item would draw attention in the middle of the road today, no one is paying it any mind in the image. In fact, it is a sanitation cart, whose purpose was removal of horse droppings from the streets. In an era before motor vehicles, the sanitation cart was a familiar, unremarkable sight, as was its cargo.

Nearby is a wagon being drawn by two horses. The driver is speaking to someone on the street, who may well be the custodian of the sanitation cart. The errand of the wagon driver is not clear, although the sign on the side of the tank on the wagon is suggestive: "Gasoline." Why is a tank of gasoline being pulled down Wyndham Street on a wagon? Perhaps that is what the custodian wants to know.

In the middle of the Square is the Blacksmith Fountain, a symbol of "industry" and the industrial aspirations of the Royal City.

In the background stands the old Post Office/Customs House. The structure projects both forwards and upwards, presiding over the Square as a reminder of the authority of the Canadian state that it and the city belong to. Curiously, the clock face that one would expect in the circle at the top of the tower is missing. This little puzzle is easily resolved: Although the clock tower was added to the old Post Office in 1903, the clock itself was not installed until late in 1906—not an unusual sort of occurrence at the time. This fact also helps to date this image to that interval.

Although the image is largely static, there is one dynamic element, namely the streetcars approaching down Wyndham Street to the left. These cars were the small open ones (no windows) that were bought for the system when it began operations in 1895. A closeup of the front of the nearest car shows that it was carrying a sign on its fender:

The sign reads, "Dolly Varden // Opera House // To-Night." This little detail dates the image to exactly one day, since Dolly Varden played in Guelph on 19 Sep. 1906 only (Mercury):

As the ad states, Dolly Varden was a "dainty comic opera," that is, a musical comedy with a marriageable woman in the lead role. In fact, the character Dolly Varden has an interesting history of its own.

"Dolly Varden" was a character from Charles Dickens's Barnaby Rudge, a beautiful coquette distinguished by her colourful manner of dress. The character proved to be a popualar one and inspired a whole style of Victorian ladies' dress that was named the "Dolly Varden" after her. It was a Victorian reintepretation of the fashions of the 1780s, when Barnaby Rudge was set. Clothing stores advertised Dolly Varden dresses, hats, and shoes. Women could wear such outfits to costume parties, where they were sure to be recognized as a "Dolly Varden."

("

Music sheet cover depicting women wearing Dolly Varden costumes." Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

With the commercial potential of this character in mind, it is no surpise that Dolly finally got her own day in the sun. Around 1900, writer Stanislaus Stange and composer Julian Edwards wrote a comic opera with her as the main character. The plot has little to do with Barnaby Rudge, beyond being set in the 1780s and featuring the gaily-dressed Miss Varden. In the opera, Dolly Varden is an very pretty, assertive, but somewhat unsophisticated orphan girl set to inherit a tidy fortune. She visits London with her jealous guardian, Jack Fairfax, who desires to have her to himself. However, she manages to outfox him and marry her true love, the dashing army officer Dick Belleville. Not only that, Dolly prevents her friend Letitia from marrying the inappropriate fop Lord Gayspark, instead setting her up with the manly Captain Harcourt.

Naturally, this sort of action called for a great deal of singing. The opera was packed with comic and romantic ditties including:

- For the knot there's no untying;

- An aural misunderstanding;

- Song of the sword;

- The girl you love;

- The lay of the jay;

- My ship's the girl for me;

- Dolly Varden (of course);

- We met in Lover's Lane; and

- A cannibal maid!

Sheet music for the opera sold well and "We met in Lover's Lane" became a number one seller.

You can hear this hit single, sung by William F. Hooley in 1902 (courtesy of the Library of Congress):

The piece was cast and rehearsed in New York but opened in Toronto on 23 Sep. 1901. In brief, it was a smash. The review in the Globe gushed (24 Sep 1901):

A crowded house last night at the Princess Theatre gave an enthusiastic reception to the new comic opera, “Dolly Varden,” which was presented for the first time on any stage by the Lulu Glaser Opera Company. So emphatic was the success with the audience of the “premiere” that the composer, Mr. Julian Edwards, who conducted for this occasion only, the librettist, Mr. Stanislaus Stange, and the star, Miss Glaser, were repeatedly called before the curtain on the close of the first act, and Mr. Stange had to make a little speech on behalf of himself and colleagues, in acknowledgment.

The lush costumes and rich settings were praised to the roof. The music was praised as "bright and tuneful" and Sullivanesque.

The songs were well recieved, with the audience demanding encores and sometimes double encores on many occasions. The composition was ambitious and demanding, and much praise was heaped on how effectively it was presented:

The ensemble finale of this act is a clever bit of work. The composer has contrived to work up the volume of sound by simple means to a grandeur approaching the effect of grand opera, and here the excellent material he had at command in the number of leading voices, showed to advantage. In the second act, in addition to a taking dance and chorus at the opening, and a pretty minuet, with a flavor of an Offenbachian Tylorienne, there may be mentioned a double quintette of fine tonal effects and light and shade, and an octette that won instant approval. The quartette of leading women’s voices also showed to advantage in this act.

Naturally, the leading lady, Miss Lulu Glaser, won particular admiration:

The star of the company, Miss Lulu Glaser, is too well known as a clever and attractive comedienne to need much comment upon her performance. Vivacious and bright, with a superabundance of spirit, and possessing a voice of good quality, she held the stage whenever she had anything to do, and as the sprightly Dolly Varden, she was well suited with the role.

The show stayed in Toronto for a week before hitting the rails. As a big hit, and seeking to be worthy of the New York stage, it stuck to the big cities and did not visit Guelph, though Guelphites must have heard of it.

Certainly, it was a big breakthrough for its leading lady, Lulu Glaser. She featured prominently in promotional material, like this picture of what must be a key scene (Hamilton Times, 26 Sep. 1903):

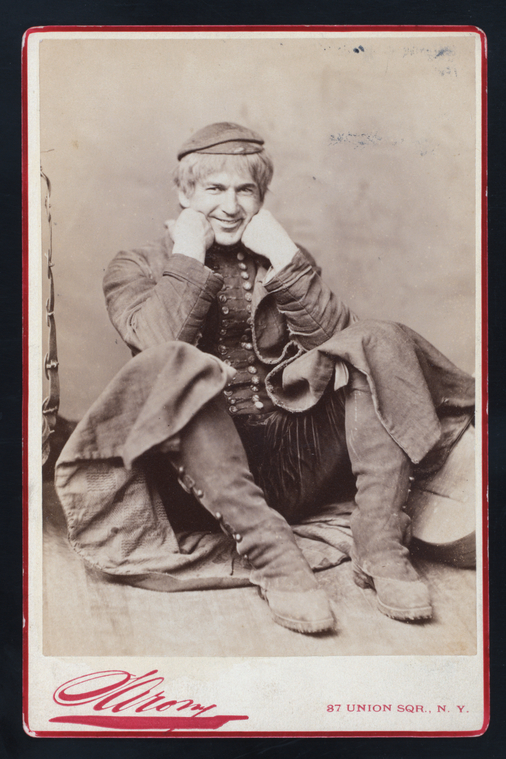

Miss Glaser's image, in costume, appeared in the promotional postcard below:

("

Lulu Glaser." Courtesy of the New York Public Library.)

A similar picture appeared on the cover of The Billboard trade magazine in 1902.

The show toured the continent twice. A company was formed to present it in Britain as well. It also achieved its highest aspiration, a lengthy run in New York. In fact, it was staged in Herald Square, New York City, for the entire summer of 1902. This was no small feat since theatres normally closed between May and September. In the days before air conditioning, it was simply not feasible to pack hundreds of people into a dark and poorly ventilated auditorium for hours while the mercury ascended the thermometer to sweltering heights. (Nor was it healthy for the performers.) The Billboard (17 May 1902) noted that the theatre was specially modified for the occasion:

Eight big noiseless fans are being set in different parts of the house and a large hole is being cut in the top of the dome of the auditorium, in which is being placed a “suck fan,” through which the hot air will be removed. New summer costumes for the whole cast are promised for Decoration Day.

Of course, all good things must come to an end and Lulu Glaser left "Dolly Varden" after the 1903–04 season. The show ran for one more season with Maud Hollins, who was Miss Glaser's understudy (I think).

There the matter may have rested, and Guelph deprived of this musical spectacular, but for the intervention of the Aborn Operatic Company. Milton and Sargent Aborn were on the lookout for a vehicle for a potential star they had picked out, Miss Lillian Spencer. She had attracted their attention after graduating suddenly from the chorus to the lead in the musical comedy "Florodora" along with her subsequent work. They felt that she would be a good fit for the lead role in "Dolly Varden" and so purchased the rights to stage another run of the show.

("The Aborn Company presents Dolly Varden;" ca. 1906. Courtesy of

the Library of Congress.)

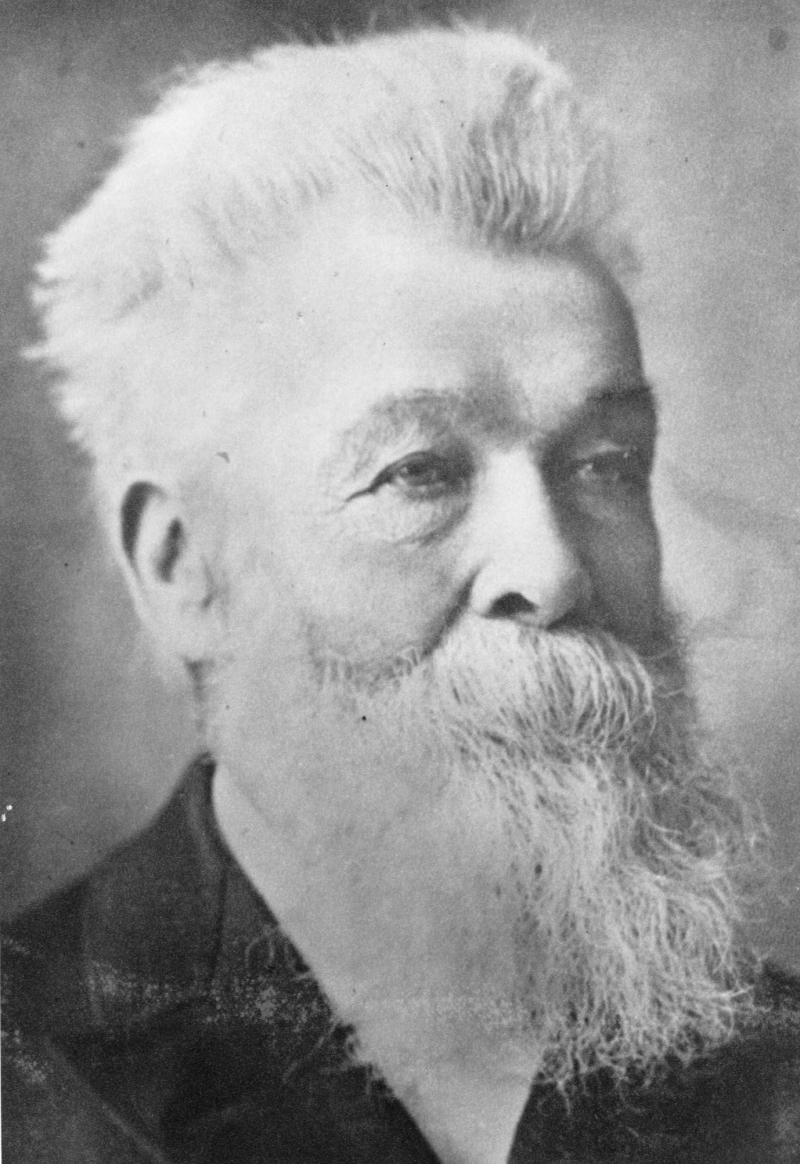

They had good reason for this judgement. Although only 21 years old, Lillian Spencer had a long history in showbusiness, particularly in comedy. At the tender age of three years, she trod the boards with American-German actor Joseph "Fritz" Emmet. Mr. Emmet cut his teeth in the post Civil War era in a minstrel troupe, where his claim to fame was singing songs in German while in blackface. He graduated to ethnic comedy, speaking and singing in a stagey German accent while yodelling and performing spectacular dance numbers.

He was most noted for his roles in the character of "Fritz," a German who experienced misadventures in various locales, while singing, dancing, and playing the guitar. The first "Fritz" show involved the character's arrival in America, with later reditions set in Ireland, Australia, etc. The plot and details of each play made little sense but that was of no consequence: The audience always wanted the same dances, the "Cuckoo song," and whatnot.

("

Joseph K. Emmett in the stage production Fritz, Our Cousin German, 1869." Courtesy of the New York Public Library.)

Part of his act was interacting with children: searching for missing ones, singing them lullabies, and so on. So it was that a three-year-old Lillian Spencer tumbled out of a prop suitcase on stage in 1888, probably during a production of "Uncle Joe; or, Fritz in a Madhouse." Audiences took to the little waif immediately and she became a professional, child actor.

Why Lillian Spencer entered the theatre at such a young age is unclear. However, the 1900 US Census shows her living in a boarding house in Manhattan along with a Jessie Spencer, age 35, whose occupation is also listed as "actress." Her marital status is listed as divorced. Although records are sparse, it seems that Jessie was Lillian's mother and may have put her on stage as a way of earning a living while being a single mother, although that is speculation.

In her early career, she was often billed simply as "Baby Spencer" and made her way as an actor and a model (The Labor World, 1 Dec. 1906):

For a number of years, she played children’s parts, and at the same time, became noted as an artist’s model. Her piquant style of childish beauty made her much sought after for idealistic paintings, and her likeness was used by many famous artists.

It would be interesting to track down some of those images.

In any event, "Dolly Varden" returned to the rails for the 1906–07 season. It played in many of the same cities as the earlier runs, such as Toronto and Hamilton. However, although the show had been revised for its new rendition, some of the novelty had worn off and it played one-night stands in smaller cities that were bypassed in previous years. And so it was that "Dolly Varden" arrived in Guelph, where, as in many other small cities, advertisements that hung on streetcars carried with them Miss Lillian Spencer's hopes for a career as a mature performer.

(The Opera House Guelph—now the site of the Guelph Community Health Centre at Wyndham and Woolwich streets— printed by the Pugh Mfg. Co. of Toronto, ca. 1910.)

The Mercury did not review the show, so it is hard to say exactly what sort of reception it got. However, the publicity stills below, published in the Sep. 12 and 14 Chatham Daily Planet provide some idea of what audiences saw.

("Lillian Spencer with 'Dolly Varden.'" Miss Spencer appears to have a flower in her teeth and is covered in straw.)

("Lillian Spencer and Huntington May in 'Dolly Varden.'" Mr. May played Jack Fairfax.)

In lieu of a report from Guelph, this short review from the performance in Duluth, Minn. (26 Sep 1906) provides an idea of the show's reception:

“Dolly Varden” was very prettily produced at the Lyceum theater last evening. The production is worthy of its title of comic opera success. Its music is a delight, and the stage pictures and costumes are charming. When first in Duluth, with Lulu Glaser in the title role, it met with great public favor, and last night this success was repeated, although Miss Glaser is no longer with the company. For some reason or other the audience was a small one, but what there was of it was enthusiastically appreciative.

Lillian Spencer is the present Dolly Varden. She is a small, very active person, graceful and light of foot, with a piquant air and a contagious laugh. Her singing was well received, and her acting full of spirit. Her support was quite satisfactory.

Piquant to Miss Glaser's sprightly, it sounds as though Miss Spencer succeeded in putting her own impression on the role. We may assume that Guelphites gave it their approval also.

To my knowledge, Miss Spencer never returned to Guelph. Her encounter with the Royal City was fun but largely inconsequential to both. Even so, the incident is illustrative of the life of small cities of Ontario in the Edwardian era, and how they were connected to the larger world. In matters of popular entertainment, Guelphites relied on the theatrical circuits centered on the metropolises of the day, as also illustrated in the case of the play Officer 666. The entertainment world has changed substantially in the meantime but we may enjoy a glimpse back in time through media like old postcards, if we are willing to look for it.

Although "Dolly Varden" did not catapult Lillian Spencer to stardom, it does seem to have provided her with a lasting career separate from her early stint as Baby Spencer. She remained in New York and featured in many productions, although not usually as the star. In 1917, she joined the

Charles Coburn company, which prompted the following review of her career up to that point (

Sun, 27 Jan 1917):

A newcomer in the company now presenting “The yellow jacket” with Mr. and Mrs. Coburn at the Harris Theatre is Lillian Spencer, who plays the roles of Duc Jung Fah and See Quoc Fah (Fuchsia Flower and Four Season Flour). Miss Spencer’s interpretation of the role of the Second wife is a sprightly contribution to the performance and a somewhat intimate rendering of a part to which full justice has not heretofore been done. Miss Spencer may lay claim to the irregularly expressed but nevertheless clearly understood title of “natural born actress.” She has been on the stage since she was 5 years old. She was known as the youngest star in the theater when she appeared in the title role of “Dolly Varden” under the management of Milton Aborn. She has played important parts with Maude Adams in “What every woman knows,” “Chantacler” and “Jeanne d’Arc,” and although she never actually publicly appeared in place of Miss Adams, she was that eminent actress’s understudy and substituted for her at most of the rehearsals of these plays. Miss Spencer has appeared also in the support of Fritz Scheff, Blanche Ring and Julian Eltinge. More recently she enacted the role of the Lisping Girl in “The Girl who smiles” at the Longacre Theatre, and also impersonated one of the matrimonial chances offered to the hero of “Seven Chances” played originally at the Cohan Theatre.

The final record that I have found about her is a notice in Variety (

17 Nov 1926) stating that she had a role in the Coburn production, "Ole Bill, M.P.".

If any reader has further information about her, please leave it in the comments below!

Pictures of Miss Lillian Spencer are not exactly common. Besides the publicity images shown above, there is a set of photographs taken in the 1910–1915 period by photographer

Arnold Genthe, who was particulary known for his images of notable persons of the day. I will show a few here; the rest are accessible at

the Library of Congress website.

A photo from Theatre Magazine (Jan 1918) shows Miss Lillian Spencer luxuriating in a Balch Price motor coat made of finest Australian opossum. She looks warm! Perhaps she continued to do modeling work in addition to acting.