Zavitz Hall began as the Field Husbandry Building at the Ontario Agricultural College (O.A.C.), then just outside of Guelph. The term field husbandry—or agronomy—refers to the study and improvement of crop agriculture. It was a natural field of study for the O.A.C. Research in field husbandry there began in 1874, although it was not until 1904 that an academic unit for it was organized within the Department of Agriculture (Lawrie; OAC Review, v. 47, n. 6, p. 348).

The College took some time in erecting a building for the unit. Lawrie remarks that the original, wood-frame field husbandry building on campus burned down as a result of celebrations that marked the end of the Second Boer War in 1902. Finally, in 1913, the College began the design and construction of a new building for this research, aptly to be called the Field Husbandry Building. It was officially opened on 12 January 1914.

This postcard was published by the Valentine & Sons United Publishing Co., Ltd., Toronto, from a photo taken sometime around 1920. It seems to have been taken in the early spring, before leaves had emerged on the vines covering the walls of the structure.

Here is a similar vantage point of Zavitz Hall today. Trust me, it is there!

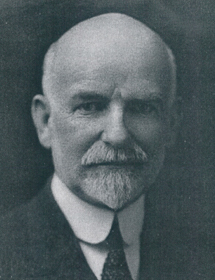

Charles Zavitz took a leading hand in design of the structure. He had graduated from the O.A.C. program in 1886 and joined the faculty as a junior chemist (Moore, "Historic Guelph" 2013). Zavitz quickly rose through the ranks and assumed leadership of the Field Husbandry unit when it was formed. He and Professor William J. Squirrel helped to draw up plans for the building (Globe & Mail; 28 June 1937). It was a picturesque building, designed in the English Cottage style, though quite a large cottage at 146 by 64 feet (ca. 45 by 20m) and three storeys high. The rural look was undoubtedly considered appropriate for a rural college. The main floor was clad in brick, with the top floor in rough cast. The attic was covered with "Asbestolate" a confection of asbestos and Portland cement, in order to help make the structure fireproof. The fire concern arose because the attic contained a dark room and was used for drying grain, which was inflammable.

Inside, the first floor housed offices, a seed laboratory, and a 120-student classroom. The second floor featured a 300-student classroom and an agronomy museum. The basement was used for grain and seed storage, and the building was heated from the O.A.C.'s central heating plant ("Recognition Banquet", 14 Apr. 1980; RE 1 OAC A0228).

As with any picturesque building, its siting was crucial, as explained by Ross Irwin (At Guelph, 4 Jan. 1989):

Charlie Zavitz was an important person on the OAC campus as superintendent of experiments and head of field husbandry. He lived in the stone cottage, built in 1882 for the college farmer, that is now Raithby House—named after its last resident.The building must have looked impressive in its largely rural setting.

The present Winegard Walk was originally a well-worn pathway from College Avenue to a row of pine trees that acted as a screen for the Zavitz house; the remnants of the screen still exist. The walkway veered west around the screen to near the front door of the University Centre, where it turned south to meet the old dairy lane.

The field husbandry building, now Zavitz Hall, was built in 1913 and opened in January 1914. It was sited to be in line with the old Horticulture Building on the McLaughlin building site and this old pathway.

Charlie Zavitz had much to say about the design and location of Zavitz Hall. One of his decisions involved the location of the south door [on the left in the postcard image], which was the entry to his office. It was surveyed to be in a direct line with the front door of his stone cottage.

Charles Zavitz enjoyed a stellar career with the O.A.C. As an academic, he was a careful and meticulous researcher who developed many new crop varieties. As an agriculturalist, Zavitz pursued research with an eye on practical benefits for farmers. He valued rural life and developed a rapport with the province's farming community. As a result, he was highly successful in directing the Experimental Union, an association of Ontario farmers—largely former students of his—who participated in crop trials under his direction.

Perhaps the best-known crop that Zavitz developed was a high-yielding barley variety labelled O.A.C. 21, which became the main barley variety grown in the province from about 1910–1950. Interestingly, O.A.C. 21 was well adapted to malting and was thus favored in beer production. The Canadian Brewers Association decided to give Zavitz an award for his service to their industry. However, as a Quaker, Zavitz was opposed to alcoholic beverages. The award was quietly delivered to him in the mail.

The association between Zavitz and the Field Husbandry Building that he helped to design remained strong. At its dedication, the Federal Minister of Agriculture, Martin Burrell, remarked that (Mercury; 13 Jan. 1914):

This building ... was erected as a tribute to the sterling worth and loyal service of Professor Zavitz, who is still with us though he has had for many years flattering invitations to leave and go across the line [i.e., to the United States]. He is here, and here I hope he will remain.Indeed he did. Charles Zavitz retired from the O.A.C. after an eminent career in 1927. Ten years later, the O.A.C. named the building after him during a ceremony featuring 500 alumni and graduates and a bronze plaque (Globe & Mail, 28 June 1937).

The rechristened Zavitz Hall seems to have remained more-or-less the same until the formation of the University of Guelph in 1964. The transition from agricultural college to independent university brought with it a major change to ideas about the campus and its buildings. For Zavitz Hall, three significant changes on the use of the campus were (Kaars Sijpesteijn 1987):

- The new University of Guelph saw itself as an urban—not a rural—institution. Thus, the new look of the campus would be that of a small city rather than a rural farm.

- The focal point for the new campus was to be Branion Plaza, south of Johnston Green, the former focus of the O.A.C.

- The University of Guelph devised a master plan for its building project but did not develop a policy for its heritage buildings.

In the absence of a heritage buildings policy, Zavitz Hall seemed to be doomed. However, events conspired to delay its demolition. Zavitz Hall provided crucial space for the new Wellington College of Arts and Sciences while the new structures were being put up (Colbert 1989). By 1970, with no room available in the new buildings—and no immediate prospect of more construction—the Fine Art Department remained in Zavitz Hall.

In 1986, a study group led by Al Brown, Director of Physical Resources, issued a report on renewal of the UoG campus. In line with 1964 master plan, the report concluded that at least $60 million would be required to deal with the University's older buildings, either for demolition or repair (At Guelph, 23 Jan. 1986). Zavitz Hall had been allowed to run down somewhat, on the assumption that it was going to be demolished anyway. It had, for example, no viable, mechanical ventilation system and the attic had been abandoned to pigeons and student frolics. It was no surprise, then, that the report called for its removal.

Controversy swiftly ensued. An editorial in The Ontarion expressed disappointment among some UoG students (Jan Sheltinga, 28 Jan. 1986):

Is it possible to put a price tag on atmosphere? Zavitz Hall may become a test case at the university of Guelph to determine whether the almighty dollar is more important than a sense of history and student opinion. ... However the potential demolition of these buildings are not as near and dear to the students collective heart as Zavitz Hall is. Although it is mostly used by Fine Art students, it is prominently located on the quadrangle of Branion Plaza formed by the concrete monsters of the Library, the University Center and the McKinnon building. It hides the sterile ugliness of the Physical Sciences building—indeed, Zavitz Hall could be considered as an obstruction to the clean, cold lines of modern architecture (or lack of it). No one can dispute the fact that Zavitz Hall embodies atmosphere. The building feels different from the other classrooms or seminar rooms on campus. It makes the student want to create, to relax, to think, to realize that the world need not be hostile and fast-paced and gray. It’s façade is not imposing and “modern”; granted, it may be a bit breezy in the chill of winter, and its staircases and ceilings are bent under the weight of old age, but it feels like home. Fine Art students seem to unanimously agree that Zavitz Hall's atmosphere is conducive to the creation of art. Although the general sentiment is that certain repairs are vital, most indicate that its demolition would be an abomination. For once, students and professors agree on something: Dr. George Todd, chairman of the department of Fine Art says, “you’d be hard pressed to find any faculty members here who want Zavitz to be demolished.” He indicates that additional space is still required, but does not think that a wrecking ball is the solution.Several important themes emerge in this response. First, the small scale and homeliness of Zavitz Hall recommended it to its occupants, in distinction to the larger scale and institutional design of its new neighbours. The matter of Zavitz Hall was a focus of tension between clashing visions for the character of the UoG campus.

Second, Zavitz Hall was central to the dignity of the Fine Art Department. The Fine Art Department had been set up by Gordon Couling and Kenneth Chamberlain from the Macdonald Institute on the formation of Wellington College in 1964 (Colbert 1989). In the ensuing years, the department developed both studio work and art historical scholarship, acquired an excellent art collection, and grew to national prominence. It also proved attractive to students, with over 300 Fine Art majors enrolled at the time. The suggestion that the department should be turned out to an as-yet undetermined location was seen as a denial of its accomplishments and importance to the University.

Third, the practical rationale for removal of Zavitz Hall remained unclear. The report included no cost estimates for repair versus replacement. Instead, the argument was based largely on the view that Zavitz was simply obsolete:

... although the building is structurally sound, the final recommendation to demolish it is based on economical and administrative whims: “It would be difficult and costly to modify the building to comply with current fire safety regulations and to make it readily accessible to the handicapped; provision of a ventilation system required to improve conditions in the studio areas would be costly”. Furthermore, the study suggests that Zavitz Hall must be demolished in order to allow completion of the central quadrangle, namely Branion Plaza, which would reduce vehicular traffic in the area.In other words, the Physical Resources department remained committed to the 1964 master plan, which mandated an enlarged Branion Plaza, and which would help to separate pedestrian from vehicular traffic.

In the absence of any concrete plan to replace the space provided by Zavitz Hall, the issue lingered. Members of the Students Administrative Arts Council (SAAC), the association for College of Arts students, appealed for Zavitz Hall to be officially designated as an historic site. The Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee, which advised City Council on such matters, was receptive and ultimately recommended the move (Mercury, 20 March 1987). (The designation was never made.) Historical designation would not prevent the University from razing the building but would make it more difficult.

In addition, the SAAC sponsored a referendum on the fate of Zavitz Hall. Nearly 80% of students who voted expressed support for retention of it (The Ontarion; 31 March 1987).

Also, University administrators began to reconsider. Initially, the "save Zavitz" movement met with resistance. Charles Ferguson, Vice-President Administration of the University of Guelph, sent a letter to City Council strongly opposing historical designation (The Ontarion, 31 March 1987). He noted the incongruity of Zavitz to its more modern neighbours and the way that it contributed to conflicting pedestrian and vehicular traffic flows.

However, Brian Segal, new President of the University in 1988, was more sympathetic. He described Zavitz Hall as a "gem" that provided an important link to the University's past (Mercury; 26 Nov. 1988). Furthermore, he felt that the option of renovation had not been adequately considered (At Guelph, 30 Nov. 1988):

The project needs “fresh eyes,” he said. “I don’t think we have begun to conceive what we can do with the building because we aren’t architects.” The university should “go down the road” to determine if it can make this building functional and beautiful, he said. Academic vice president Jack MacDonald added that the University has determined the Department of Fine Art to be an area of strongest academic need on campus. Its students and faculty are working in “deplorable conditions,” he said.In other words, renovation should be considered not only out of respect for Zavitz Hall but also for its current occupants. A committee was struck to study the matter, including director of Physical resources Al Brown, Dean of Arts David Murray, Fine Art chair Ron Shuebrook and Fine Art professors Walter Bachinski and Chandler Kirwin.

In March 1989, a feasibility study on renovation of Zavitz Hall was issued by Lett/Smith, an architecture firm with much experience in renovating and repurposing of heritage structures ("Feasibility Study", 1989). In brief, the report concluded that Zavitz Hall's external structure was sound and that its interior could be renovated to suit the Fine Art Department and meet the Ontario Building Code. Concerns about vehicular traffic could be addressed by locating a service area at the northwest corner of the building, away from most pedestrian travel. The estimated cost of renovations was pegged at $4.6 million, a considerable sum but about half the cost of erecting a new building that would re-house the Fine Art Department.

On 25 May 1989, the University of Guelph Board of Governors approved the proposal and the expenditure (At Guelph; 31 May 1989). Renovations began in 1990 and were completed in 1991. Sculpture studios were located in the basement so that heavy objects there could be adequately supported. The first floor held department offices, printmaking facilities and a collections room. The second floor housed a library, seminar rooms, faculty offices, drawing studios and galleries. The attic was finished for drawing and painting studios, taking advantage of the opportunity for having skylights there. The main entrance, facing the University Centre, served as a showroom for student artwork. A two-storey glass enclosure facing Branion Plaza gave passers by an opportunity to observe art work in progress.

On 11 November 1991, the new Zavitz Hall was officially opened with a special ceremony including students and faculty of the Fine Art Department, President Brian Segal, and other dignitaries (At Guelph, 20 Nov. 1991). A postcard featuring a drawing of the renovated Hall was sent as an invitation.

(Illustration by D.R. Montgomery/Courtesy of Ron Shuebrook)The renovated Zavitz Hall continues today as headquarters of the School of Fine Art and Music.

How can the survival of Zavitz Hall be explained? The odds initially seemed to be stacked against the building, since it was labelled as obsolete in the University of Guelph master plan and enjoyed no protection as a heritage building. Several factors emerge from the story recounted above:

- Occupation: Despite having no place in the new master plan, Zavitz Hall continued to be occupied. It served as the home of Wellington College and, later, the College of Arts. The initial growth spurt that came with the University of Guelph meant that, for many years, the University could not do without the space and facilities offered by Zavitz Hall.

- Progress: The University's master plan called for the removal of Zavitz Hall from Branion Plaza as part of its vision to become an urban and modern institution, as distinct from its predecessors. Nevertheless, a significant group of people still saw Zavitz Hall as part of a coherent vision of the University's future. Some proponents felt that the building was a "gem" that contributed to the look and feel of the Plaza. Some felt that the Hall served as a reminder of the institution's significant past achievements, a tradition that should be kept in view.

- Respect: The initiative to raze the building was a blow to the Fine Art Department, for which no alternative housing had been secured. In view of the success of the Department, the notion of evicting it, perhaps to rented quarters in town, seemed unfair.

- Politics: The University administration was initially unwilling to seriously consider renovation of Zavitz Hall. Its own Physical Resources department saw the Hall only as a derelict. The arrival of Brian Segal as President changed matters. As an outsider, Segal was not committed to demolition of the building. He was also sympathetic to the position of the Fine Art Department. The Department then had room to flesh out and gain support for the renovation option.

- Luck: The history of Zavitz Hall reveals more than a little good fortune for its supporters. Until the Board of Governors' decision in 1989, its survival was not assured.

Since its inception in 1914, Zavitz Hall has been a tribute to Charles Zavitz and his work. And so it remains today.

Thanks to Ron Shuebrook, who began as chair of the Fine Art Department in the middle of this controversy, for his insights into its history. Ron's experience with building preservation while at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design played a significant role in motivating work on the option of renovating Zavitz Hall.

Thanks also the staff of the University of Guelph archives for their assistance in locating source materials.

NB. Charles Zavitz is sometimes confused with Edmund Zavitz, a relative, who was also an O.A.C. professor and taught in the Forestry Department. Edmund Zavitz was an important promoter of reforestation in Ontario.