Born in Guelph in 1838, John Belmer (J.B.) Armstrong was the eldest son of Robert and Janet Armstrong, recent immigrants from Scotland. Robert was a blacksmith who had set up a smithy on Macdonell street east in 1834, where he specialized in making wagons and axes. John later boasted that his father had made the first axe in Ontario (Globe, 10 Sep 1886), though this claim may be open to dispute.

Disaster struck when Robert died in 1848, after which his widow ran the business (Mercury, 12 Dec 1892). Adding to the family's woes, the smithy burned down the next year. However, it was rebuilt and leased to Mr. Thomas Anderson, who resumed the manufacture of carriages. It was under Mr. Anderson's tutelage that young John learned the blacksmith's trade.

Subsequently, J.B. decided to seek his fortune south of the border, working for a time in New Jersey and then in Eddyville, Kentucky. There, when the American Civil War broke out in 1861, the carriage trade was disrupted and J.B. returned to his hometown.

Back in Guelph, J.B. entered into a partnership with his brother William at the family factory, going under the name of The Armstrong Bros. The business seems to have gone under a number of names in subsquent years. By 1866, the smithy was styled the "Excelsior Works," then apparently a common name for a foundry looking to gin up a reputation for excellence. By around 1870, the business was also known as the Guelph Carriage Company or J.B. Armstrong & Co. In 1876, J.B. entered into partnership with Thomas Scarff (William having left some years previously), to form the J.B. Armstrong Manufacturing Company, which finally stuck.

The new company had some impressive new digs. In 1875, J.B. had a new structure erected where his foundry stood at what is now 92–98 Macdonell street, named the "Armstrong Block" in his honour. The new edifice was described fulsomely in the Mercury (21 July 1917):

... J.B. Armstrong has erected a block of stone stores three storeys in height, which are second to none in the town for elegance of design and substantial appearance. The stores have a frontage of 70 feet. The most westerly has a depth of 70 feet and the other part is 40 feet in depth. Besides this the old shop fronting on the street has been raised. Two thirds of the ground floor of the new building is to be used as a show room. The additional accommodation in the two flats above the old shop is to be used for trimming room, etc. Entrance to the yards and shops in rear is obtained through an archway between the new building and the shop.Although much altered inside by the Cooperators in the 1990s (which added an attic storey), the facade constructed by renowned Guelph masons Matthew Bell & Son was kept and graces the streetscape to this day, as can be seen in the image below:

J.B.'s plans for his works were ambitious. Besides making carriages and other vehicles, the company began to make carriage parts to sell to other manufacturers. Among the most sought out was the patented Armstrong Carriage Spring, sold across North America and the United Kingdom, as described breathlessly in the Guelph Herald (22 May 1878):

The principle of tempering adopted in this establishment is in use by no other manufacturer in the Dominion, and is the result of many years close study and observation by Mr. Armstrong. Suffice it to say that the process is patented in Canada, the United States and Great Britain, and the effect of its working is such as to command the admiration of those competent to judge such matters.Another section of the works produced some of the toughest buggy seats then to be found on Earth:

As an instance of the great strength of the patent iron seats for buggies it is only necessary to say that though their weight is no more than if made of wood they are so strong that a two hundred pound biped recently stood with a foot on each end of the seat, and though he exerted his whole strength was unable to warp it out of shape.Beyond carriage parts, the company also diversified into parts for agricultural implements, such as rake teeth, cultivator springs, harrow teeth, and so on (Globe, 6 Aug 1892).

One of the ways that J.B. decided to advertise his wares was by postcard. These cards from the early 1880s were very similar to the earliest ones adopted in Canada, which featured an address on the front and a message on the back, without any picture.

Compare this card sent to J. Sheldrick of Hagersville on 8 July 1882 with the postcard sent by Guelph lawyer William Merritt ten years earlier:

The only notable difference is that the address of the British American Bank Note Co. is now simply "Montreal" instead of "Montreal & Ottawa."However, the back of this card is quite different. Instead of a hand-written message, it contains a pre-printed advertisement for the wares of the Guelph Carriage Goods Co.

The carriage step depicted look as though it could support the weight of a very substantial biped!The back of this card is reminiscent of the trade cards that were then popular with stores that sold consumer goods. Concerns such as the Bell Organ & Piano Co. would distribute cards with pictures on one side and advertisements on the other for giving away to potential consumers. Stores would give cards to people who walked in the door, hoping to increase their chances of a sale.

In this case, the Guelph Carriage Goods Company has used an illustrated postcard to entice another business to purchase their carriage parts. Mr. Sheldrick must have been a likely prospect, as he was sent several similar cards in the weeks following the one above:

This card is a little less interesting as it does not depict the Adze eye nail hammers on offer.In any event, Mr. Sheldrick was favored with at least two more advertising postcards:

At this point, you may be wondering if Mr. Sheldrick was "sold." As it happens, a later postcard appears to confirm that he was. This sort of card is known as the "scroll style" for the obvious reason that the "Canada Post Card" label is now contained within a fancy scroll. (The "stamp" has also been changed to have an oval frame.) The scroll style was introduced in 1882, and Mr. Sheldrick was sent this card on March 5 of the next year.The back of the card contains a hand-written message recorded within a form for business correspondence:

The message on the back reads:Mar 5th, 1883 // J. Sheldrick Esq // Hagersville // Dear Sir // In reply to your favor of 2 inst[ant]. // we will carry out your instructions // about orders but have received none // from you since our Traveller was // with you[.] // Yours truly // Guelph Carriage Goods Co.So, it appears that Mr. Sheldrick's interest was piqued by the advertising cards, to which he responded, prompting a visit by a traveling representative of the Guelph Carriage Goods Co., as was standard practice. Follow-up postcards, in the new style, were sent the following year.

J.B. Armstrong & Co. continued to send interesting pictures through the mail. Below, for example, is the back of another scroll-style postcard sent to Messrs M.A. Stephens & Sons of Glencairn, Ontario in 1894. It contains both a form letter acknowledging receipt of an order and a lovely drawing of the Armstrong "Peerless" road wagon:

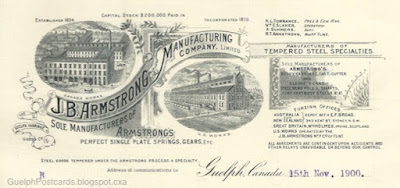

Along with many other going concerns, the Company also had drawings of its factories printed on its letterhead. Here is an example sent to a potential supplier in 1900: J.B. Amstrong & Co. are the picture of prosperity, showing off its works in Guelph (upper left) and in Flint, Michigan, (right, established in 1889). Information on the right-hand side indicates that the Company had offices in Great Britain and Australia as well.The prowess of the Company had not gone unnoticed and was the subject of a glowing review in the Toronto Globe (6 Aug 1892). Besides relating the breadth and reach of the company's lineup, the article provided some interesting pictures. The first was a (somewhat murky) photograph of the works taken from the Bell Organ Co. building across Macdonell street:

(Courtesy of Wellington County Museum and Archives, A1985.110.)The second was a nice drawing of the man himself:

(Courtesy of Wellington County Museum and Archives, A1985.110.)The last was a picture of J.B.'s bolt hole at 85 Queen street, built by his brother-in-law James Massie, which J.B. named "Gilnockie" after the residence of a Scottish ancestor:

Gilnockie can still be glimpsed from Queen street.The extent of the Guelph Carriage Works can be seen in the map below, in which the plan of the Works from the Fire Insurance Map of 1892 is superimposed on a Google Maps satellite image of the north side of Macdonell street.

As noted in the Mercury, the Works extended all the way from the Armstrong Block on Macdonell street to Quebec street at the rear (upper right corner of the inset), now covered by the Quebec Street Mall.Just as J.B. Amstrong had ascended to the pinnacle of success in the vehicle trade, he was carried away by death (as was a common expresison at the time), dying on 11 December 1892, at the age of 54, following a period of ill health. He was buried in what is now the Woodlawn Cemetery.

The J.B. Armstrong Manufacturing Company continued the trade for a number of years but was wound up in 1913.

J.B. Armstrong was a model of the industrialization of Guelph in the Victorian period and left behind a substantial legacy. The Armstrong Block remains in place along Macdonell street and the Blacksmith Fountain is now located in Priory Square, next to the former Guelph Carriage Works.

(The Blacksmith Fountain in Priory Square, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)J.B.'s personal legacy is also suggestive. The importance that he attached to the trade, and to control of it, is indicated by some of the terms of his will:

... in his will in 1888, he stipulated that his son, Bertie, would not receive his full inheritance, at age 25, if he had not proved himself to be industrious and frugal or if his mother did not approve of his marriage.How Bertie felt about these terms, I don't know.

In addition, although the postcards sent by the Guelph Carriage Goods company are ephemeral, they provide us with an instructive reminder of the conditions in which J.B. did business. When I, for one, think about horse-drawn buggies and sleighs, my impression is of the quaintness of the Victorian era and how romantic it might have been to travel the streets of the Royal City in them.

This may have been the case but the cards also remind us of the centrality of horse-drawn transportation to contemporary life. As Tarr (1971) points out, cities depended on horsepower not only for personal transportation but for shipping. Adoption of steam railways meant that tons of goods from long distances could be delivered to cities in a short period. These arrived at centralized locations, such as warehouses at the edge of town, and were then delivered by horse-drawn vehicles. The expansion of railway networks reinforced this trend.

As a result, the working horse population in the United States became quite substantial:

[In 1900,] Chicago had 83,330, Detroit 12,000, and Columbus 5,000. Overall, there were probably between three and three and a half million horses in American cities as the century opened, compared with about seventeen million living in more bucolic environments.The situation was similar in Canada.

To be put to work, millions of carriages and carriage parts were needed, which the Guelph Carriage Goods Company helped to supply. For the business to work, reliable and affordable communciations were needed to coordinate activity, which the postcards shown above helped to provide. (Not coincidentally, J.B. was one of the first Guelphites to have a private telephone line installed in his house in 1879.) For J.B. Armstrong and his contemporaries, there was nothing quaint about the carriage trade or the means of carrying it out.

For fun, here are some representations of the vehicles made by the Guelph Carriage Goods Company as depicted in their ads. (Evening Mercury, 25 July 1869.) (Toronto Globe, 27 November 1886.) (Guelph City Directory, 1892.) ("The Armstrong Standard Buggy," ca. 1896. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Musems, 2002.88.2.)