It being Farmers' Day at the Exhibition, the main events concerned agriculture. Judges examined specimens from across the province in several categories, including breeds of cattle, sheep, and pigs. Also scrutinized were varieties of honey, sugar, bacon, apples, plums, peaches, grapes and other fruit, not to mention domestic wines and numerous dairy products. A contest among agricultural implements of all descriptions was also held. Besides these events, there was an essay contest and what might now be called a battle of the bands.

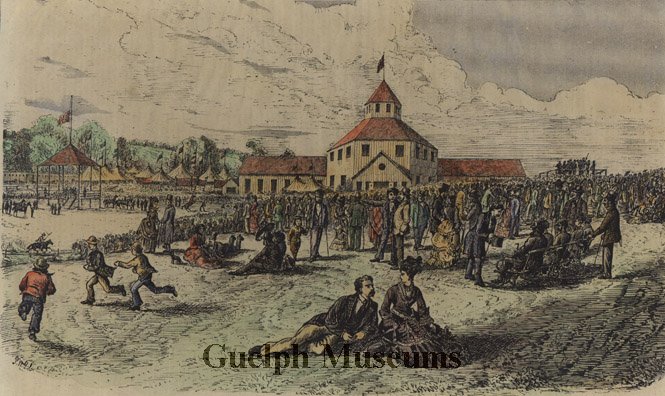

("Bird's eye view of the Guelph Exhibition Buildings and Grounds," ca. 1875. Kathleen Street is in the foreground. A legend enumerates many other buildings and features. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums.)One feature of holding the show in Guelph was that farmers could make a short trip and inspect the Ontario Agricultural College on the hill south of town, where their sons might go to learn the latest in the agricultural arts.

("Detail of aerial plan of Guelph by H. Brosius, 1872." Rows of pens and stables can be seen right (north) of the Palace and along Exhibition Street (bottom) and Kathleen Street (top). The gatehouse at the corner of London Road and Exhibition Street can be seen near the left edge, with the horse-judging ring and stand just above. Courtesy of Wellington County Museum and Archives, A1985.110.)Although every corner of the Exhibition grounds was full and the space contained many buildings and structures, arguably the most remarkable one there was the rotunda, sometimes referred to as "the Palace." It was a large, two-storey, octagonal wooden structure featuring four wings (later reduced to two). It had several functions during events like the Provincial Exhibition, such as to hold exhibits of items including stuffed birds, clothing, crockery, butter, and whatever else the occasion demanded. In addition, it could provide office space for event organizers, and the open central area could be used as a dance floor!

(The Main Building (Palace), stalls, and wicket of the old Exhibition Park. From Allan, D. (1939) "About Guelph: It's early days and later." Notice how drawings of the Palace tend to squash its central section; compare with photographs below.)To understand the Palace, it helps to go back to the beginning of Exhibition Park itself. The initial layout of Guelph included a large Market Square in the middle of town. Its founder, John Galt, expected that Guelph would be the central point of an agricultural region and thus made this provision for market space. The Market Square, where the VIA station, City Hall, and Armory now stand, fulfilled that function but became too constrained by construction and the arrival of the Grand Trunk Railway right through the middle of the area to meet expanding demands for more exhibition space.

(Map of the Exhibition Grounds from the Illustrated Atlas of the County of Wellington, 1878, superimposed on a Google Maps image of the area as it is currently laid out. The Palace stood astride what is now the footpath across the park at Mont Street, roughly where the lavatories are today.)As a result, exhibition organizers looked at properties outside of the central city for more room, and their eyes settled on the Catholic Glebe north of London Road. The glebe was a plot of land that was granted to the Catholic Church in Guelph in order to support it through development, leasing, sale and so on. In 1870, the committee for the Central Exhibition negotiated the purchase of this property from the church for $5000. Funding was supplied by the Town of Guelph, the South Wellington Agricultural Society, and a loan from the Imperial Loan Society of Toronto. Guelph now had its own Exhibition Grounds.

The question then was how to develop it. Of course, organizers needed structures and facilities to hold regional exhibitions. However, organizers also had their eye on hosting the Provincial Exhibition, a grand affair organized annually by the Agricultural Association of Ontario. The Association had a policy of limiting this Exhibition to big centres—Toronto, Kingston, London, Hamilton, and Ottawa—where facilities and population would (hopefully) support a big show and a good turnout.

To join this club, Guelph's organizers would need some substantial buildings. These would include plentiful stables, pens, and sheds, as well as halls able to house big exhibitions and office spaces. Primary among these would be main building capacious enough for multiple uses as well as tasteful enough to impress officials with the provincial organization. Construction, if not design, of the main building was entrusted to local builder Bernard McTague.

("Crystal Palace (Provincial Exhibition Building), London, Ontario," from the Canadian Illustrated News, 30 October 1875. Courtesy of Ivey Family London Room, London Public Library, London, Ontario, Canada; PG F70.)There is no record explaining the reasoning behind the Palace's octagonal plan. Octagonal buildings were unusual (and remain so), the main example in the neighbourhood being the Speedside Church. In all likelihood, the organizers simply instructed McTague to imitate the Palace in the Exhibition grounds in London, Ontario, which had been built on an octagonal plan for London's Provincial Exhibition in 1861.

("Exterior view of the Crystal Palace after the building was relocated to Sydenham, South London, following the exhibition of 1851." Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)The reason that the building was called "the Palace" is not hard to guess. The Great Exhibition of London in 1851 featured a main building known as "the Crystal Palace" because it was essentially a giant greenhouse with an all-glass exterior. This structure set the precedent for subsequent exhibitions across the British empire, so that exhibition buildings in Toronto, Hamilton, London (Ontario) and so on were all referred to in this way. No exhibition worth its salt could be without one.

(This association also suggests that perhaps, like the Crystal Palace in London, the Palace in Exhibition Park had no foundation. Instead, it may simply have rested on a board pad, though no record I have makes any mention of this aspect of its design.)

("Guelph, Ont.—The Central Exhibition: Interior of the Rotunda.—By P.W. Canning." From the Canadian Illustrated News v. 10, n. 4, p. 213; 3 October 1874.)The central portion of the Palace was 84 feet (25.6m) across while the four wings were each 40 by 60 feet (12 x 18m). The upper storey in the main portion provided an interior gallery, where people could walk around the inside of the building and take in some more refined exhibits, such as arts and Ladies' work. The City Directory for 1873 mentions that this building cost a substantial $9000 to put up!

Naturally, many other structures were required to house such large exhibitions. The Palace was initially accompanied by three smaller ones, one for agricultural implements, one for grains and roots, and a third for poultry. Besides these, a row of horse stables (600 feet/183m), a row of cattle pens (900 feet/275m), and a row of sheep and pig pens (500 feet/152m) were laid out. In addition, a fenced ring about 400 feet (122m) in diameter was constructed in front of the horse stalls, complete with a central judges stand, for exhibiting draft and carriage horses.

Other buildings were added (or repaired) over the years as required, including many for the Provincial Exhibition of 1883.

The entire park was enclosed in a board fence and an entrance built at the corner of London Road and Exhibition Street, where admission could be charged.

("Guelph.—Agricultural machinery at the Central Exhibition.—From a sketch by F.M. Bell Smith. Canadian Illustrated News, v. 6, n. 18, p. 285; 2 November 1872.Exhibitions were held in the fall of 1871 and 1872. In his "Annals of the Town of Guelph," Burrows (1877) notes that both were a big success. The 1871 edition was held on October 10 through 12 and attracted 7000 entries from across Ontario. About 15,000 people attended each day and $8000 in prizes awarded altogether. The 1872 edition was held on October 1 through 4, and was a "magnificent success." Lt.-Governor Sir William Pearce Howland attended and gave an address that was received with enthusiasm.

Once the success of these home-grown exhibitions established the exhibition grounds in the local culture, serious thought was given to formalizing additional uses. In 1873, the Town Council adopted a bylaw setting out the rules. First, the name "the Central Exhibition Park" was adopted as the official moniker for the property. After some warm debate, the Council adopted a rule that the Park could be rented out for other uses, such as festivals, bazaars, or picnics, at their discretion. Fees were set at $20/day for the park plus buildings or $10/day for the buildings alone. Lessees were limited to charging 25 cents admission for events when the whole grounds were let. The grounds would remain open the general public as usual when only the buildings were let. Open hours for public use were set at 6 a.m. to 9 p.m. from 1 May to 30 September, and from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. from 15 October to 30 April. Provision was made for a caretaker to police these regulations.

A motion was made to forbid the selling of alcohol on premises. However, the motion was voted down. Temperance would not be the rule at Guelph's Exhibition grounds.

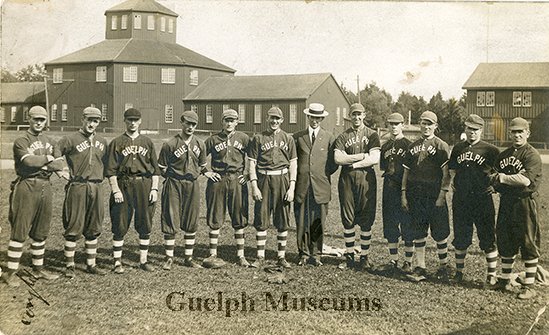

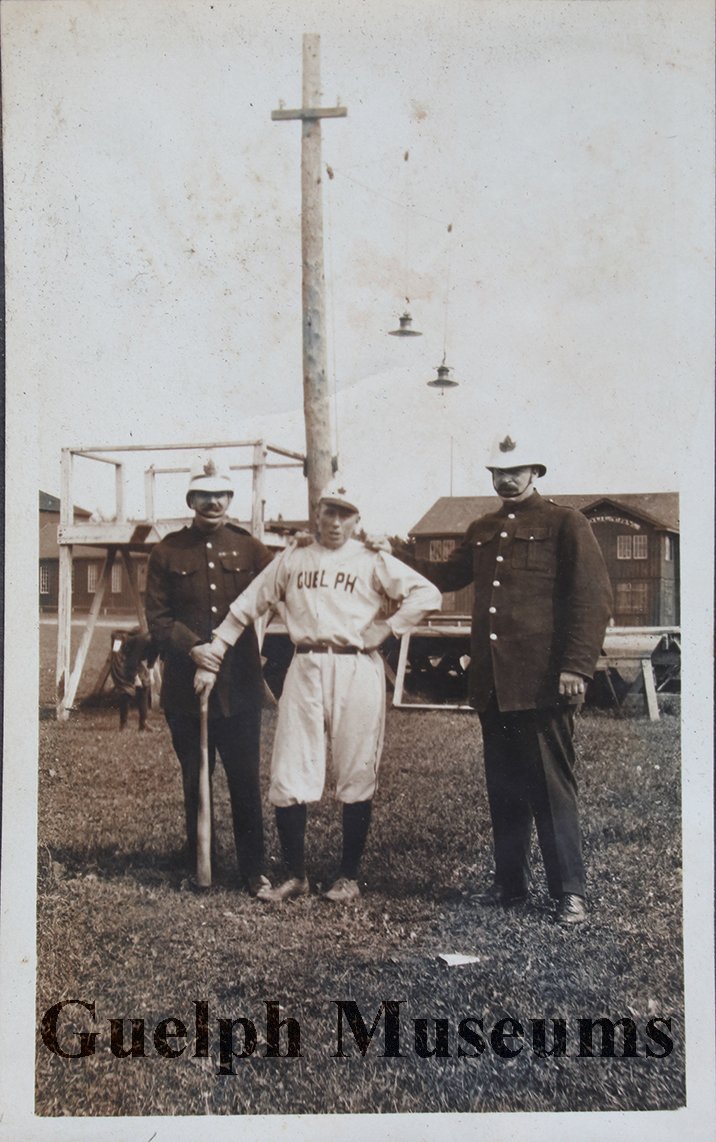

("Postcard, William A. Mahoney with Guelph Ball Club, 1912-1913." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2014.84.351.)It took little time for community organizations to take advantage of the opportunities afforded by the new park. On 24 June 1874, for example, the St. Joseph's Hospital held a "Grand Charity pic-nic" on behalf of the Aged and Orphans in their care. Many games were on tap, including ten-pin bowling, foot ball, croquet, quoits, swings, merry-go-rounds, and many more. Naturally, the sporting centrepiece was a base ball game between the "world-champion" Maple Leafs and some selected locals. In the Palace, there would be a Grand Bazaar and an exciting Wheel of Fortune, where valuable prizes would be given to lucky winners.

("Exhibition Park, Guelph, Can." ca. 1910, featuring the park's bandstand. Postcard published by the International Stationary Company; from the author's collection.)Musical entertainment would be provided by Lawrence’s Silver Cornet Band starting at noon.

("Horse racing in exhibition Park. There are two jockeys in buggies being pulled around a track. In the background are the large playing fields of Exhibition Park. There are some kids playing baseball on the field." ca. 1903. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 2007.21.1, p. 11).Perhaps the most interesting affair (after baseball) would be the horse races. It appears that a half-mile track had just been built around the central area of the park, permitting races to be held. On tap were (1) running, single dash, for horses that have never won public money, (2) trotting to harness, best two out of three heats, open to all horses, and (3) running, single dash, consolation stakes, $5, for horses beaten in first race. The entry fee was one dollar for each horse, with prizes of $10 for a first place finish, $7 for second, and $3 for third. For reasons of propriety, no betting was allowed.

("Exhibition grounds, Guelph, Can." Postcard published by the International Stationary Company, probably on the occasion of Old Home Week, 1913. Note the grandstand and race track on the right, parallel to Kathleen Street, the Poultry Building in the middle background, and the Palace to the left. From the author's collection.)Countless other events were organized by community organizations. To mention just one more, an association of ex-Guelphites from Toronto visited their old haunts on 28 August 1893, foreshadowing the Old Home Week celebrations of the twentieth century. A train laden with eight cars of former residents arrived in the city, where they related tales of the good old days when wolves howled outside of people's doors and the like. After a warm reception at the C.P.R. station, the group made their way to Exhibition Park to celebrate in style. The weather turned rainy, so games were cancelled and the multitude made for the Palace. There a concert was given by the 30th Batallion Band until the time came for supper. At that point, 500 people were seated around seven large tables set out on the ground floor. A meal was served and devoured, toasts and speeches made, and then the visitors made their way back to the station to return to the Big Smoke.

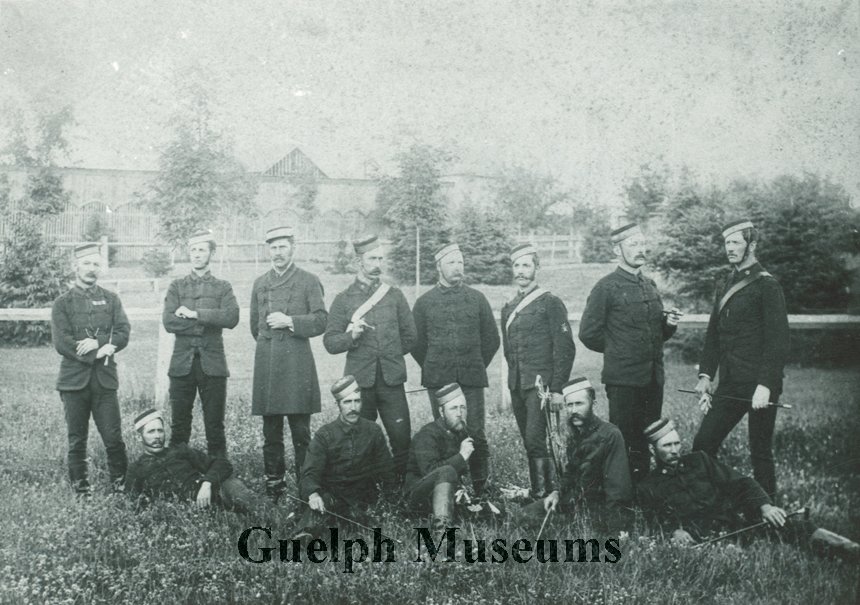

("Artillery camp at Exhibition Grounds, fifty years ago," ca. 1875. Tents appear to be pitched inside the horse-judging ring. From the Guelph Evening Mercury Centennial Edition, 20 July 1927.)Mention of the 30th Battalion band also points to the frequent use of the Park by local military units. In October 1873, for example, the 30th Battalion camped in the Park to hold its annual inspection there, under the watchful gaze of Col. French. On the first of October, they showed their stuff to the Colonel, performing artillery maneuvers in the horse ring. Their movements were disciplined and precise: Each gun was drawn by six horses and and followed by an ammunition wagon drawn by four more, so it would have been easy to get fowled up.

In the following year, the Battalion camped in the park once again and was joined by Battalions from Bruce and Perth Counties. Altogether, there were about 1200 personnel camped in the Park, along with all their artillery, gear and animals! Their disposition is described as follows (Mercury, 30 June 1874):

At the extreme north-west corner the tents of the 30th Battalion have been pitched. South of them the Bruce Battalion is located, on the same ridge. On the level ground east, and fronting the cattle sheds are the Waterloo and Perth Battalions. Between the main Exhibition Building and the horse stables are pitched the tents of the Wellington Field Battery, and here also their guns are placed. Towards the south end of the horse ring are the tents of the Brigade staff. Attached to each Battalion is a large tent for the officers’ mess: also a canteen, where no liquor stronger than beer is allowed to be sold. Eight men are allotted for each tent. The cooking arrangements are of the simplest and most primitive description. A square hole is dug in the ground, where the fire is placed, and pots, pans, &c., are suspended from a temporary fixture above in true gipsy fashion. The rations which are ample, are all supplied by requisition sent to the Supply Officer, and these again are re-divided among the companies and messes. The wells on the ground supply sufficient water for the whole camp. The tents belonging to each Battalion are generally laid out with great regularity, and look like a small town under canvass while the cooking and other domestic operations—the rushing to and fro of orderlies, the knots of men which here and there are seen eagerly discussing some question pertaining to the camp—make up a scene at once novel and full of interest.This was likely the largest military encampment in the history of the park. ("Wellington Rifles" (30th Battalion), ca. 1885. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, Grundy 154.)

So far as I am aware, the period of semi-regular military encampments in the park concluded with the celebration of the Queen's birthday (24 May, in case you've forgotten!) in 1888. On that occasion, the Artillery brigade was joined by the Royal Grenadiers of Toronto, by special invitation of Mayor A.H. Macdonald, then in command of the Guelph Artillery battalion. The Grenadiers were well-known for their particiation in the North-west Resistance (or North-west Rebellion), particularly at the Battle of Batoche in 1885. Eight companies of the Grenadiers were in town to participate in parades, maneuvers, and athletic events over a three-day period.

Interestingly, although provision was made for at least some soldiers to sleep in the "horticultural hall," many chose to room in local hotels instead. In any event, the officers of the Grenadiers were entertained with a special dinner laid on by the city in the wings of the Palace.

("34th [Infantry Battalion] in the Exhibition Grounds in Guelph," 19 May 1915. Courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada, 3403547.)Military events continued to be held in the Park. During the Great War, for example, the 34th Battalion and 16th Field Artillery were given a send-off in the Park in May 1915. The band of the 153rd Battalion camped in the Park in July 1916 to receive well wishers and perform concerts. On 17 April 1917, the 64th Battery performed maneuvers in the Park that were recorded for movie men from Toronto. Alas, this footage seems not to have survived.

("Colours presentation to 153rd Battalion Wellington militia, Guelph, 1916." Dignitaries including local MP Hugh Guthrie and later-mayor Harry Westoby take in the proceedings. Courtesy of Wellington County Museum and Archives, A1955.19.16.)Perhaps the most surprising events were re-enactments by veterans of prominent battles of the Great War, organized by the Great War Veterans Association (GWVA). For Dominion Day 1918, after a band concert and a display of Scotch and Irish dancing by four little girls, a number of veterans staged a re-enactment of the battle of Vimy Ridge, with fireworks supplying appropriate sound effects.

The next year, the GWVA organized a similar event, featuring musical and dance performances, a baseball game, a baby contest, etc., as well as a re-enactment of the storming of the Hindenburg Line. This, it seems, was an elaborate affair (Mercury, 2 July 1919):

It was a very realistic bombing attack, the men in khaki going over in two waves, and the bombs and artillery crawling in a way that gave the spectators a fair idea of what an attack meant in a small sector of the front.To add to the versimilitude of the occasion, plans were made to include a tank, although obstacles were encountered in the execution of this plan:

There were casualties and prisoners, and Sergt. Dan Anderson led his troops with much dash. Sport Pearce, in complete Hun uniform, helmet, covercoat, even long top boots, was captured and taken back to the barb wire cage. Even the rum ration was in evidence for, after the objective was reached, the "tots" were dished out from the orthodox S.R.D. jar, the wounded receiving first attention, and though, of course, it was only "two percent," the boys seemed to relish it.

The tank arrived on the scene, according to schedule, but it was found impossible to get it into the grounds except by allowing it to use its natural method of smashing its way through all obstructions. The committee did not feel justified in allowing it to crash through the fences, as the Parks Committee might have considered that a little too realistic.Battle re-enactments were not unheard of in celebrations of this sort but participation of a tank is, as far as I can tell, unique. ("Exhibition building, Guelph, Ont." Postcard published ca. 1910 for A.B. Petrie. Courtesy of the Keleher Collection.)

One thing that was different for the 1919 show than the year before was the absence of the Palace. At the outset of 1919, the City Council decided to demolish the main buildings in the Park and revise the fence arrangement. The wood and windows of the Palace were to be piled up in the park and sold off (Mercury, 13 March 1919). In the new arrangement, the southern section of the Park, next to London Road, would no longer be fenced in, so that public access was made much easier.

No reasons for this decision are noted in the Mercury. However, there were several reasons to do away with the Palace. First, it had been some time since it served its original purpose as a venue for indoor displays during exhibitions. The Provincial Exhibition, held in Guelph in 1883 and 1886, had been discontinued after its final hurrah in London, Ontario, in 1889. Simply put, it was a money loser and could not compete with profitable and annual events, especially the Toronto Industrial Exhibition (predecessor of the Canadian National Exhibition). Guelphites were happy to take the train to Toronto to see the "Ex" rather than try to host a periodic rival in town.

("Winter Fair Building, Guelph," postcard published for Henry Garner Living Picture Postcard Co., Leister England, ca. 1910. From the author's collection.)Second, Guelph started its own, annual Provincial Winter Fair, starting in the year of the earlier fair's demise, 1889. A special Winter Fair building was constructed in the Market Square to accommodate this event. This arrangement was much more convenient, was focussed on agriculture, and made money.

("Exhibition Park," real photo postcard, possibly the 1916 visit of the 153rd Battalion. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2014.84.476.)So, the Palace had become something of a white elephant for the city and it was dismantled and removed in 1919, apparently with little fanfare. Today, as we look back, its presence is recalled only in old maps, drawings, and postcards.

Of course, there is lots more to say about the early days of Exhibition Park. Hopefully, future blog posts will explore this interesting topic.

("Guelph Maple Leaf ball player with 2 police officers, ?, Fred and Agnes McTague," ca. 1915. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2017.1.36.)Sources consulted include:

- Heaman, E. (1999). The Inglorious Arts of Peace: Exhibitions in Canadian Society during the Nineteenth Century. University of Toronto Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment