Although postcard publishers tended to prefer summer photography, postcards were sent all year round, and this card was actually dispatched from Puslinch to Guelph on 31 December 1914, when the Royal City and its surroundings had be socked in under repeated snowfalls.

Addressed to Mrs. James D. McPherson on York Road in Guelph, the message relates to the holiday season:

Dear Jim & Belle:—Of course, the year 1914 was an unusual one in Guelph. The Great War had begun a few months earlier and Canadians were still unsure what it would amount to. Many young men had left with the Canadian Expeditionary Force and were still in Britain training for combat. Herbert Philp wrote a letter home to his family, which they subsequently published in the Mercury (24 December), under the ironic title "Salisbury mud a wonderful thing." In it, Philp speaks eloquently of the frustration of the contingent:

We got the photos and you could not have sent us a better Christmas box. Glad to hear baby is growing so well.

Wishing you all

A Happy New Year

Aunt Flora

For, despite the eagerness of practically every man in the contingent to be "over the way," we are still wallowing about in England's mud.Philp explains that the conditions were fine and dry on their arrival, and they pitched their tents in a "slight valley." Then down came the English rains, leaving their modest dwellings with:

ambitious rivulets flowing either through them or snuggling close to their sides. Not a tent but contained a pool of water.When the weather let up, the tents were moved up slope but the cookhouse remained down in the valley, meaning that everyone had to line up there three times a day, in whatever weather, to get their food. The result was frequenty cold tea and soup and soggy bread at meal times. (Detail of "Herbert William Philp," no date; Courtesy of William Ready Division, Archives and Research Collections, McMaster University Library, via The Canadian Encyclopedia.)

Philp finishes his letter thus, "But, so far as excitement and entertainment are concerned, Salisbury Plains still runs a close second to the grave."

(Herbert Philp's many and eloquent letters home throughout the Great War have been collected by Ed Butts in the book, "The Withering Disease of Conflict: A Canadian Soldier's Chronicle of the First World War." It is available from the Guelph Historical Society and I highly recommend it!)

War news was a mixed bag. Accounts of terrible battles were featured, but the general tone conveyed the sense that the Allies had the upper hand and German defeat in the near future was still a possibility, though not by Christmastime.

Rumours of German attacks on or in Canada circulated. For example, a national article printed in the Mercury (1 December) related a scheme set in motion for German forces to take over Quebec City. A concrete structure made the previous year near St. Anne de Beaupré by a German movie crew in 1913 was thought to be a bunker intended as a weapons cache for a surprise attack launched by sea. Luckily, British naval superiority had frustrated this plan, it was thought.

The many Canadians of German descent in the region also caused concern. A letter to the Editor (11 December) attempts to address rumours of a German-Canadian fifth column thus:

Editor of the Mercury.As ever, conflict breeds suspicion and mistrust, well-founded or not. Locally, misplaced suspicion of German- and Catholic Canadians resulted in the Guelph Novitiate Raid of 1918. ("Evangelical Ch., Morriston." Courtesy of Wellington County Museum and Archives A2009.124, ph. 31342.)

Dear Sir: Who are the meddlers who have been reporting to Guelph authorities that secret meetings are being held in Morriston by the Germans and German-Canadians?

There are no secret meetings held in Morriston to my knowledge. Perhaps the meddlers had reference to the revival meetings, held in the Evangelical church, which are held annually. These meetings are not secret, but sacred, and people of all nationalities are welcome to attend.

Are such meddlars as these throughout the Dominion interested in uplifting our Canada? No, they are too ignorant to realize the harm they are doing their own village and community, also their own country, Canada.

Yours respectully,

A life-long Mercury reader.

Compared to previous years, the Xmas shopping ads in the Mercury seemed subdued. Still, they were far from absent. The D.E. Macdonald & Bros. shop urged Guelphites to "Hurry up! Only two more Saturdays before Christmas" (11 December). Extensive gift suggestions for him, her, and baby were provided, along with an illustration of Santa Claus hauling a prodigious sack of goodies.

Similarly, Moore and Armstrong noted that there were only nine shopping days left (14 December): "If you have not got the Christmas Spirit yet, you will have it in large measure when you get to the White House," that is, their store on Wyndham street.Their illustration also showed Santa Claus carting a super-sized sack of gifts. One can understand the look of relief on the jolly old elf's face at the sight of the very wide chimnney before him!

If nothing else, Santa's message was to go big or go home, or both!Even Santa Claus was not unaffected by the conflict in Europe. This cartoon shows how low German Kultur had sunk with the war (22 December):

The caption says, "An act of barbarism: Not only are the Germans firing on the Red Cross and flags of truce, but they are rendering the work of Santa Claus difficult and hazardous."Being magical, Santa had the means to rectify the situation, as shown in a subsequent cartoon (26 December):

Here, Santa deploys what I assume is a stocking full of doorknobs to give Kaiser Bill a jolly good thrashing.People on the home front carried on. The Guelph Musical Society held a parade downtown on 9 December. The performance was marred somewhat when large bulldog followed the squad down Wyndham street. The drummer found that the dog would bite the drumsticks whenever he raised them to beat the kettle drum. Fearing that he might be "minus a wing" if he provoked the dog further, the drummer ceased drumming and the band had to proceed without their bass.

The animals did not have it all their own way. A bear cub named "Teddy" had been kept as a curiousity at the American Hotel on Wynhdam street for most of the year. Having reached the size of 200 lbs, Teddy was sent Bernard Schario, the butcher, who turned him into roasts and steaks as a holiday feast for the hotel residents (24 December).

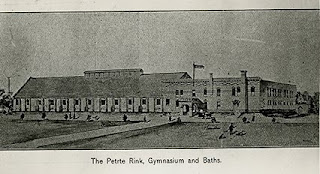

The skating season took shape. With the cold weather, Guelphites were soon skating on the pond above Goldie Mill. Skating also began indoors at the Royal City Rink (formerly Petrie's Athletic Park and Rink) at Wellington and Gordon streets.

(Detail of "The Petrie Rink, Gymnasium and Baths," 1898. Courtesy of Guelph Museums 2014.84.2.)Curiously, the street railway company decided not to open their usual skating rink on Howitt's pond, on the basis that it would not be "a paying proposition" (18 December). In previous years, the rink behind the streetcar barns on Waterloo road had been run as an attraction to get people onto the streetcar system in winter.

Perhaps they had too much competition. The City had decided to fund a rink on the grounds of the Guelph Collegiate Institute on Paisley street. A room in the basement was even made available for people to put on their skates (22 December). Perhaps this level of comfort and style attracted skaters who might have been inclined to travel to the streetcar rink in previous years.

("Collegiate Institute, Guelph, Ont." Postcard printed for Waters Bros., Guelph, ca. 1910. Courtesy of Guelph Museums 2009.20.1.)The Royal City Rink was also home to Guelph's very first NHL team! Yes, Guelph entered a team in the 1914–15 Northern Hockey League senior series (21 December). Although some of the players trying out for the team were from out of town, lots of local boys turned out to show their stuff, including Allan, Anderson, Stricklerr, Greer, Hayes, Spalding, Ogg, King, Mowat, and Bulgin.

The side lost their first exhibition game against the Dutchmen of Waterloo (26 December). Although the Guelphites mainly acquitted themselves well, the superior size of the Seagramites gave them a distinct advantage, resulting in a 5–2 win for the visitors.

Another tilt against the same team was arranged for the first regular season game. This time, the Royal City skaters were better prepared. The result was a "wild sort of affair," beginning with a dispute over whether one of the Guelph players was a professional—strictly forbidden! The play was very physical and Referee Knell of Berlin (Ontario) "had his hands full."

The police had to be called in to break up a melee after the crowd joined in an on-ice altercation in the second half. Tied at the end of regulation play, the game went ten minutes into overtime before Guelph's centre, McGregor, put the home team up 7–6.

At the Reformatory (or "Prison Farm"), the provincial government announced plans to install an abattoir on site (31 December). The Ontario prison system required 600–700 tons of meat annually in its operations, which was obtained from private butchers. Building an abbatoir at the prison meant that prisoners could be employed to perform the butchering at a lower cost than private butchers, saving the system some $50k a year. In addition, prisoners would learn skills that they could use to obtain regular employment as meat dressers in private industry after release.

("Ontario Reformatory Guelph, Jan. 1915 The Abattoir." Courtesy of Guelph Museums 2014.84.1276, p. 59, ph. 3.)A final point of interest came with the annual, municipal elections. First, there was some talk of not holding the elections at all, in view of the war situation (17 December). But, the election went ahead as usual.

Besides electing a Mayor, Aldermen (Councilors), and other officials, citizens of Guelph were asked to weigh in on the following by-law, "Are you in favor of municipal votes for married women?" (8 December). The 'Women's Franchise plebisite' was carried by a majority of (male) voters 1140 to 838 (5 January 1915).

Women's groups had long campaigned for women's suffrage in Ontario. In the Edwardian era, efforts tended to focus on municipal voting. In 1914, the Canadian Suffrage Association, led by Dr. Margaret Gordon, had lobbied many Ontario municipalities to hold referenda on extending votes to women. It appears that Guelph was one of 33 municipalities where the effort met with success, albeit for married women only.

Women's role in the Great War led to further support for the cause. In 1917, Ontario women finally gained the right to vote in provincial elections.

In many respects, the holiday season of 1914 was like those of previous years. Even so, as the prospect of the end of the conflict in Europe receded, it was clear that times were changing and that the New Year would bring on many new challenges.