Thus began the notorious "Guelph Novitiate raid."

The Novitiate was a Jesuit school that had been founded only a few years before when the Jesuit Society purchased a 300-acre farm north of Guelph from Thomas Bedford (later a prime mover behind the John McCrae Memorial Garden in town.) Young men studied there to join the priesthood.

The Society built a generous structure to house the school. Happily, photographs of the Novitiate are preserved in a couple of postcards. The first is a real-photo postcard, that is, a photograph printed on postcard stock, by Lionel O'Keeffe, a Guelph photographer, ca. 1920.

The building is an impressive one, looking much like a fancy hotel, to my eye. Certainly, it must have looked commanding at the brow of the hill from the Elora Road. I wonder if Macaulay felt any trepidation when approaching it.

The second postcard shows the other side of the building. The fieldstone walls of the first and second floors were left from "Langholm", the name that an earlier owner, Charles Mickle, had given to his stone farmhouse on which the Novitiate was later built. A subsequent owner, Maurice O'Connor, called the property Mount St. Patrick and had a large portrait of the saint under the gables of his house. Perhaps it was only natural that it became the site of St. Stanislaus Novitiate later on (Mercury, 20 June 1927).

This postcard was printed by the J.J. Pinsonnault Co. of St. Jean Quebec, probably also around 1920. Together, the postcards leave an impression of a substantial building, designed to impress.

The story of the raid has been told in detail in several venues (see below). Relying on these sources, I will outline the events presently but want to set the scene first, framing the raid in the context of the Conscription Crisis of 1917 that gave rise to it.

The Great War was not going as hoped. In 1917, the situation on the western front looked grim. Germany was certainly winning the conflict in the east, where the Russian revolutions seemed destined to knock that country out of the war. In that event, the German army would be able to deploy many more forces to the western front in 1918 to launch an all-out assault. In spite of American entry into the war, prospects for victory were far from bright.

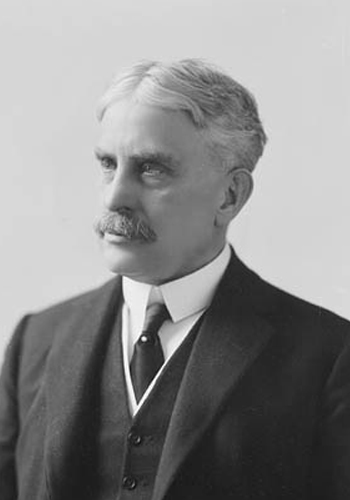

This was the situation as presented to Canada's Prime Minister Robert Borden as he attended the Imperial War Conference in London in March–April 1917. Even though Canada had contributed mightily to the war effort, and had just won a famous victory at Vimy Ridge, the ultimate outcome remained in grave doubt.

Robert Borden (Miesianiacal - Library and Archives Canada (PA 028128)/Wikimedia Commons)

The Imperial War Cabinet wanted Canada to do yet more, mainly to supply more soldiers. Perhaps to sweeten the deal, the Cabinet adopted Resolution IX, which offered (nearly) full autonomy to the British Dominions, including Canada. Borden determined to act. He decided that the only effective response to the situation would be to introduce conscription. Although he had previously maintained that compulsory military service would not be necessary, Borden now saw things differently. The result was the Conscription Crisis of 1917.

A federal election was due late in 1917. At that point, Borden's Conservative Party had uncertain prospects of returning to power. However, the conscription issue enjoyed broad support in English Canada. So, running on a pro-conscription policy would substantially improve his chances of success. At the same time, conscription was less popular in French Canada and rural Ontario. French Canadians were more likely to view the conflict as an imperial, British affair instead of a Canadian matter. Also, many were unhappy about government policies that they viewed as anti-French, such as Ontario's Regulation 17, which severely curtailed French-language schools in the province. Farmers in rural Ontario also tended to oppose the policy, fearing that removing their young sons from the farms would threaten their livelihoods.

As a result, a policy of conscription was sure to cause upheaval along existing, social fault lines.

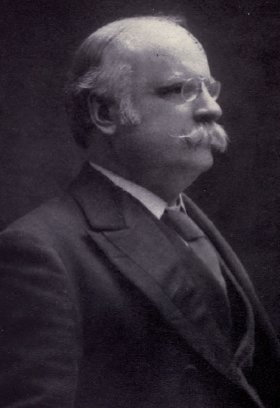

Borden undertook several measures to improve his odds of success. Knowing that many English Liberals supported conscription, he formed a Unionist coalition in which Conservatives and pro-conscription Liberals could both join. Hugh Guthrie, formerly a Liberal MP for Wellington South, joined this coalition.

Hugh Guthrie (Library and Archives Canada (PA 027564)/Wikimedia Commons)

The Conservative government also passed acts to swing the electorate in their favor. The Wartime Elections Act enfranchised women in federal elections for the first time but only those with close relatives serving in the military. It also disenfranchised Canadian citizens who came from "enemy-alien" countries, that is, Germany and Austria, and were naturalized after 1902. The Military Voters Act enfranchised all soldiers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, even those who were recent British immigrants. Military voters could vote simply for the "Government" or "Opposition", in which case the government itself would choose which riding to allocate the ballot to.

These measures were calculated to boost votes for the Unionist government and suppress votes against it.

To quell unrest in rural Ontario, Major-General Mewburn, the Minister of Militia and Defence, pledged that conscription would not be applied to farmers' sons. Mewburn's pledge was made official by an Order-in-Council.

Major-General Sydney Mewburn (Canadian Annual Review, 1923/Wikimedia Commons)

After perhaps the bitterest and most divisive election in Canadian history, the Unionists were elected by a large majority and conscription was duly enacted. The election drove a wedge between various social groups, especially English vs. French, and Protestant vs. Catholic. It is in this context that the significance of the Guelph Novitiate Raid of 1918 should be viewed.

In English Canada, opposition to conscription among French (and therefore mainly Catholic) Canadians was regarded as unfair and perhaps treasonous. By 1918, the view that the war represented a clash between civilization, in the body of the British Empire particularly, and barbarism, in the guise of Germany especially, was well established. Thus, the very survival of Canada as a civilized country was at stake. Conscription was seen as necessary for victory, so opposition to it was viewed as tantamount to Kaiserism. Furthermore, enlistment in French Canada trailed that of English Canada, so that it appeared that French Canada was reaping the benefits of resistance to the Huns without making a fair contribution to it.

In Guelph, suspicion began to fall on the Novitiate. In no small part, this suspicion originated in a provision of the Military Service Act that exempted clergy from conscription. Among Protestants, young men studying for ordination were not regarded as clergy. Thus, they were subject to conscription. Among Catholics such as the Jesuits, on the contrary, young men studying for ordination were considered bona fide clergy. Thus, they were exempt from conscription. Not a few Protestants saw this situation as unfair. In addition, rumour had it that the Novitiate might be hiding "slackers" from elsewhere. The neighbouring riding of Waterloo North had voted Liberal, which some Guelphites thought was out of sympathy with Germany. Perhaps Hun sympathizers from Waterloo were abroad in the region, where they would, it was thought, find aid and comfort for their treasonous schemes at St. Stanislaus.

Jesuit authorities had taken measures to head off problems. In September 1917, the Bishop of Hamilton visited the Novitiate to tonsure the students, that is, to officially induct them into the Jesuit order as clergy. Also, Father Henri Bourque, the Rector, arranged for official documents to be drawn up for each student at the Novitiate, confirming their status as clergy. Students were instructed to carry these documents with them at all times when off the Novitiate grounds.

Yet, increasing pressure was put on military authorities to do something. Members of the Guelph Ministerial Association complained publicly about that the Novitiate students were in violation of the Act. Rumors began to circulate that the Jesuits had dug tunnels to keep slackers or the sons of wealthy Catholics out of the trenches. It was also speculated that the Jesuits had acquired a cannon and were stockpiling ammunition for some sort of uprising.

Henry Westoby, city alderman and registrar and secretary-treasurer of the local enlistment league, complained to military officials of Father Borque's repeated refusals to register the students for conscription. He reiterated some of the rumours in circulation and said that there was going to be an "explosion" unless military officials took action. Local Unionist MP Hugh Guthrie passed on to Major-General Mewburn the names of three men reported to be hiding out at the Novitiate. Taking this information at face value, Mewburn issued a communique to his staff to follow up, which was passed on to military police in London, Ontario, with an ambiguous note to "clear out" or "clean out" the Novitiate. (A later search failed to find the note, so its wording remains unclear.)

Captain Macaulay and nine men were duly assigned the job and arrived in Guelph, in plain clothes so as to be discrete. Macaulay and several men searched the buildings while others covered the grounds, in case any slackers or subversives tried to flee. To make a long story short, no such people were found, neither were there any tunnels or ammunition stockpiles. Of the three young men on Mewburn's list, only George Nunan was actually there, although he was in compliance with the Act.

The situation quickly became heated. Macaulay began to interrogate members of the Novitiate. As it happened, these included the Reverend Father William Power, then head of the Jesuit Order of Canada and described as "a formidable character," and Father William Hingston, an army chaplain just returned from a tour of duty in France, who appeared in his Captain's uniform. In addition, Father Bourque had got on the phone and alerted a number of people including Patrick Kerwin, their lawyer, Thomas Bedford, then Justice of the Peace, and Judge Hayes of the County Court. Judge Hayes advised Father Bourque to allow Macaulay to inspect the grounds and interrogate members of the Novitiate. This Bourque did, under protest.

Macaulay proceeded to interrogate students while making no effort to ascertain their status under the Act. That is, he did not ask for proof of their membership in the clergy, although their documentation was on hand. As it happened, one of the students was Marcus Doherty, son of Charles Doherty, the Justice Minister of the Unionist government. The younger Doherty was able to reach his father on the phone, who then contacted the Adjutant for Canada, Major-General Ashton. Ashton was put on the phone to Macaulay and told him to return to town without making any arrests. Macaulay had identified 36 people he considered suspicious and was about to take three away with him. Given the situation, he removed himself and his squad from the grounds.

Charles Joseph Doherty (A history of Quebec: its resources and people, 1908/Wikimedia Commons)

In the end, only one person at the Novitiate could not be immediately accounted for. In fact, he turned out to be a demobilized soldier, Private O'Leary, with a distinguished service record. Father Bourque made a written complaint to General Mewburn, who replied with an official apology and blamed the affair on Macaulay. A later inquiry endorsed this view and Macaulay was reassigned to Winnipeg.

At this point, the story moves away from the Novitiate itself. Naturally, the raid was the talk of the town and beyond. The government invoked a press ban, so discussion was either informal or conveyed by clergy from their pulpits. There remained a great deal of resentment about what was seen as special treatment of Catholics in general. The Minister of Justice was seen as particularly responsible, as an Irish Catholic from Montreal who had a son of military age at the Novitiate itself. (It is worth noting that Marcus Doherty had already been declared unfit for military service by Army doctors.) Others argued that judgement should be reserved until the facts were in.

The press ban collapsed on 19 June when the Toronto Star broke the story, after which it became a cause of much discussion nationally. Press reports in the Guelph papers tended towards conciliation, as accounts of the raid came in and it was realized that the whole affair was casting the Royal City in a rather scandalous light.

After a few weeks, the press of outside events drew attention away from the raid. It was later played down. For example, no mention of it appears in the Centennial edition of the Guelph Mercury in 1927, which contained a lengthy history of the city's first century. Although the divisive issues that played a role in the raid simmered on, the raid itself was perhaps seen as part of the unpleasantness of wartime that was best left unrecalled.

The old Novitiate building soldiered on until it burned down in 1954. It was afterwards succeeded by the Ignatius Jesuit Centre, which remains on the top of old Mount St. Patrick today.

The account above is taken from the following sources:

- Rutherdale, Robert (2004). Hometown horizons: Local responses to Canada's Great War, Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 178–191.

- Nash-Chambers, Debra (2006). "Sectarianism and scandal: The 1918 Novitiate raid in Guelph Township," Wellington County History 19: 4–16.

- Butts, Ed (2017). Wartime: The First World War in a Canadian town, Toronto: James Lorimer & Co., pp. 117–133.

- Dutil, Patrice and David MacKenzie (2017). Embattled nation: Canada's wartime election of 1917, Toronto: Dundurn Press.

Although largely forgotten today, the Conscription Crisis and its aftermath remain, arguably, the ugliest political upheaval in Canadian history. English and French Canadians felt unfairly treated by the other. Feelings surrounding the Guelph Novitiate Raid relate significantly to French Canadian enlistment or the apparent lack of it. French enlistment was lower than in English Canada, a point that vexed many Guelphites. However, it is worth remembering some further points. About half of all Canadians in the Canadian Corps were British born. Enlistment among Canadian born men was never equal to their proportion of the population in either French or English Canada. In no small part, this situation was a result of a massive wave of immigration of single, young men from Britain in the Edwardian era, a wave that bypassed French Canada. So, the supply of unattached young men available for service in English Canada was much higher than in French Canada, both numerically and proportionally. Details like this were largely overlooked in the heat of the moment.

No comments:

Post a Comment