("The graduating class", featuring the May Queen on her throne with her entourage. OAC Review, v. 23 n. 11, July 1911, p. 570)

The time was 4:30pm on 26 May 1911 and the place of this seemingly pagan ritual was the campus of the Macdonald Institute, just outside of Guelph, Ontario. On the face of it, it seems odd that an archaic, medieval ceremony should be undertaken in Edwardian Guelph. Indeed, the reasons for it are not altogether clear. Yet, the ritual does seem to represent an effort to bring a greater sense of Englishness to the young women at the Institute just outside the Royal City.

As explained by Anne Bloomfield (2001), the May Pole dance was originally part of the May Day festivities practiced in medieval England, as well as much of the rest of Europe. In the springtime, a pole was selected and cut from a nearby forest, trimmed, decorated, and erected on a special site. A May Queen was crowned and festivities, including many dances, were enjoyed.

Celebration of May Day was forbidden by royal edict in 1644, perhaps to appease Puritans during the English Civil War (McDermott 1859, p. 12). Although the edict was repealed with the Restoration of 1660, May Day did not return to its former popularity.

However, May Day festivities were revived during the Victorian era. In Britain and all over Europe, increasing industrialization and urbanization were accompanied by nostalgic attitudes towards lifestyles of the medieval and renaissance eras. Combined with growing nationalism, one result was increasing interest in rural folk culture, including folk music, dances, and celebrations. True Englishness, it was thought, could be found in these elements of times gone by.

In the course of the 19th century, more and more English cities began to revive—or introduce—May Day festivals. They began to compete with each other to attract more visitors and tourists. For example, Knutsford became noted for its May Day celebrations and remains so today. Eventually, many such festivals dried up as their market share shrank or people's interests changed.

May Day festivities also become integrated into public education. In particular, the influential public intellectual John Ruskin incorporated the celebrations into his teacher training curriculum. He felt that May Day rituals and dances inculcated British youth with a proper sense of their heritage from the rose-tinted "Merrie England" of yore. However, like many revivalists, he did not balk at modifying traditions to suit contemporary tastes. For example, instead of the usual, very tall May Pole with decorations attached to the top, Ruskin promoted a shorter pole with ribbons hung from the top that could be woven into patterns by dancers. In fact, this sort of pole and dance may have originated in Italy. In any event, Ruskin thought it comely and his influence ensured that this version of the pole became widespread.

In Britain, May Day celebrations continued to be promoted to children during the Edwardian era, when the Macdonald Institute was created. There is very little discussion of the importation of May Day festivals into Canada but it seems likely that it arrived here along with the many British immigrants of the time.

It is unclear what caused the festival to be introduced at the Macdonald Institute in 1910. Snell (2003, pp. 50–51) notes that the ceremony was chosen by the Macdonald students themselves as a fitting representation of their values on graduation, apparently cultivation and femininity as these qualities were then understood. Ross & Crowley (1999, pp. 96–97) describe the proceedings as follows:

A queen was chosen, the Macdonald gymnasium decorated profusely in flowers assembled from around the campus, and young women attired in dainty white frocks. Twenty maidens entered the gym carrying brown and gold shepherds’ crooks adorned with buttercups. They then formed an arch through which the other students, carrying flowers, entered. The May pole bearers came next. When the queen entered surrounded by her maids of honour, she knelt to receive her crown from principal Mary Urie Watson before ascending to her throne on a specially constructed stage adorned with foliage. Once the pole had been decorated and dancing was finished, president Creelman and the May queen led the way for the planting of the graduation tree. Tea on the lawn followed, with an evening program that included Victrola selections and fireworks to cap off a perfect student planned performance.Sounds like good fun!

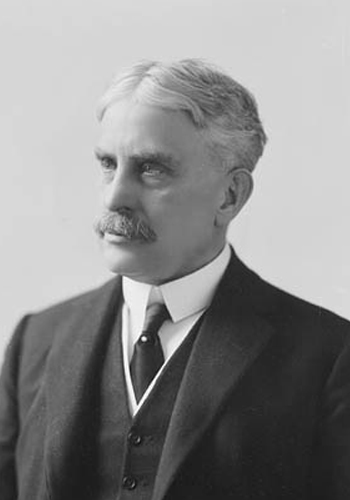

The event was a hit and it was decided to hold another one the following year. This time, photographers were on hand in force. The 1911 May Day fete was fulsomely described in the OAC Review (v. 23, n. 10, pp. 570–572). The author notes that the event was held not on May first, as in England, but on May 26, because the greater length of Canadian winters precluded the appropriate activities until a later and warmer time of the month. The proceedings are described as follows:

At 4:30 o’clock, on May Day, the Macdonald girls in dainty white frocks all assembled in the gymnasium and after forming in a line two they marched out to the campus where the events were to occur. First came about twenty of the girls each carrying a brown and gold shepherd’s crook and butter cups. The crooks were joined together at the right distance by a slender rope which when each girl took her proper place, marked off a large space on the green for the dances and crowning of the Queen. Then came the rest of the Juniors carrying blossom covered boughs and wildflowers. Following these came the May Pole bearers, who carried out, and placed in position the May Pole. The girls formed in a long double line through which the Queen was to pass followed by her maids of honor.The postcard below is a real-photo card (a photograph printed on postcard stock) showing the Juniors emerging from the gymnasium of the Macdonald Hall to take their places within the rope enclosure.

Then, the ceremony continues:

Two tiny tots—dainty little flower-girls—led the way strewing the path to the platform with blossoms. How sweetly gracious and stately looked the Queen as she went to her crowning followed by two train bearers! The Queen took her place, her maids of honor grouped about her and she knelt to receive the crown [Macdonald Institute Principal] Miss Watson placed on her queenly head.

The picture below shows the flower girls leading the May Queen from the gymnasium and into the regal enclosure, followed by her train bearers.

The Queen's name is give as "Miss Wink Frank", a byname that I am unable to decipher. It would be interesting to know her real name.

The next photograph shows the Queen, duly crowned, seated on her throne and attended by the maids of honor and her flower girls. Note that this photograph is identical to the one printed in the OAC Review above, conforming that these pictures are of the 1911 event.

Then came the dances:

After the May Pole had been decorated and the several dainty dances were finished, [OAC] President Creelman and the May Queen led the way to the spot chosen for the planting of the 1911 graduation tree, and the time-honored class ceremony was performed.

The pictures below are of these dainty dances around the May Pole. The OAC Review names two of the dances, the "Rheilander" and the Pole Dance.

The most obvious feature of the "Rheilander" is that it is danced in pairs and does not involve direct interaction with the May pole.

I assume that "Rheilander" is a misspelling of "Rheinlander", which is a 19th century German polka. However, the postures of the dancers shown in the pictures suggest something more like the "May pole minuet" depicted in some of Barbara Irwin's postcards of Edwardian, American maypole dances.

Then there is the May Pole dance, which seems to involve each dancer holding a ribbon and weaving a pattern through their dance.

Since the dancers seems to be going in opposite directions and dodging in and out, this dance is likely a version of the Plait, in which the dancers weave their ribbons into a fabric against the pole. Here is a modern rendition:

After this, tea was served by the Housekeeping class, accompanied by speeches, songs, and tunes on the Victrola. After dark, fireworks were again launched from atop the Institute, courtesy of President Creelman. The assembled then went into the gymnasium of the Hall for the remainder of the evening.

It is interesting to note how the May Day fete was an entirely feminine affair. Traditional May Day festivities included men, particularly as mummers and in sword dances. However, masculine education in Edwardian Canada had been largely militarized by this time, so that young men were more involved with marching, camping, and, of course, playing football. Thus, it made sense to all to hold a May Day fete involving only the young women of the Institute.

Although the May Day celebrations were a hit at the the time, they did not persist. Snell (2003, p. 113) notes that the occasion was superseded by the Daisy Chain graduation ceremony in the 1920s, although a May Pole dance remained a part of this event into the 1930s. Perhaps the onset of the Jazz age and the rigors of the Depression made this slice of Merrie England seem out of place.

In case you are keen to see more postcards of maypole dances, then point your browser to the late Barbara Irwin collection site.

Let's not forget that the City of Guelph held its own May Day events in the 1920s, featuring Miss Vida Brill as the May Queen in 1922!

If you are keen to stage a genuine, early 20th Century May Day event of the type conducted at the Macdonald Institute, there are many manuals from that era to consult. Here is one to start:

- Lincoln, JEC (1926). "Festival book: May-Day pastime and the May Pole," New York: AS Barnes & Co.