Before their departure, Mr. R.T. Hagen, Chief Engineer of the TSR confirmed that regular service between Guelph and Toronto was slated to start on Saturday the 14th although there would be but one car per day each way. On 1 May, after a period to identify and correct any difficulties, more frequent service would begin.

The new service was immediately well patronized. Although regular railway service between the Royal City and the Queen City had been established for decades, the idea of riding the trolley between the two (or points along the way) seemed to fulfill a need.

The cars themselves sound as though they were quite inviting. Car 101, a passenger car built at the Preston Car and Coach Company, was well appointed, finished in attractive cherrywood. The upper sashes of the side windows were glazed with leaded glass. Cars were entered from a center stairway that reached to street level for added convenience.

At the back of the car was the Main Room, featuring green, plush, upholstered, high-backed seats with headrests and footrests. A polished bronze handle on the aisle sides allowed passengers to seat themselves with dignity. A pushbutton was provided in each setting so that riders could inform the motorman of their desire to get off at the next stop. Overhead were luggage racks for storage and a three-ply, poplar veneer ceiling. A private toilet was located at the front.

At the front of the car was the Smoking Room, outfitted with low-backed seats upholstered with green pantasote—imitation leather—for a look reminiscent of a gentlemen's club. In service, the Smoking Room would have been filled with clouds of hot ash and tones of gentlemanly conversation. At the front of this room was the motorman's compartment, with the pedals, gears, levers, bells and gongs needed to control the train and communicate with its passengers.

Travelers on the TSR often used it to commute to larger centers for shopping or socializing. It became common practice for the Railway to add a trailer car to the Saturday train for shopping purposes. Ladies from smaller places along the line would visit Guelph to do their shopping and could deposit their purchases on the car over the course of the day. In the evening, the car would leave the Royal City to haul its load of goods and women on their trip home.

Traveling to parks was also a popular use. Guelphites were known to ride the TSR to attend dances at Edgewood Park in Eden Mills. In 1925, the TSR purchased Eldorado Park, a private park along the route in Chingoucousy Township, now within the town of Brampton. The idea was to boost ridership on the line by providing an attraction for passengers to visit, much as the Guelph Radial Railway (streetcar) built Riverside Park in 1905. A Ferris Wheel and Merry-Go-Round were added to make the proposition more attractive.

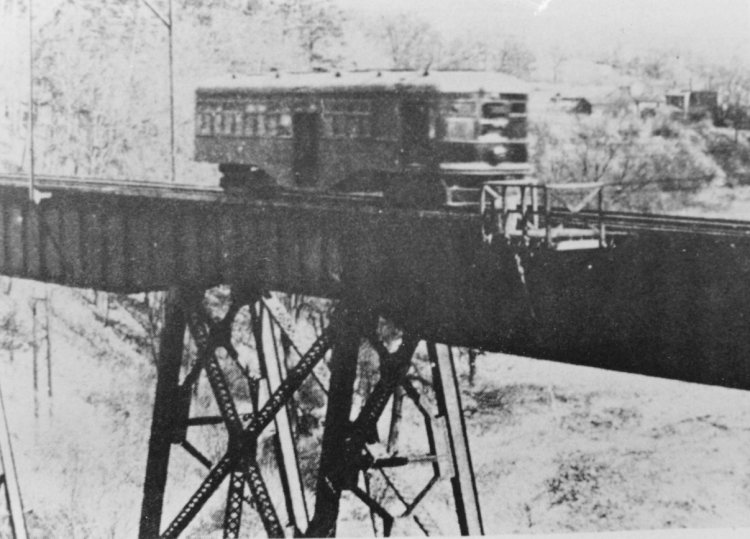

("Electric railways, Canada (1923)"—apparently a special excursion train from Toronto to Eldorado Park. Courtesy of British Pathé)

The Toronto Suburban Railway began life in 1890 as the Weston, High Park & Toronto Street Railway Company, with service centered on the town of West Toronto Junction (now known simply as "The Junction"). Two prominent railway wheeler-dealers, Sir William Mackenzie and Sir Donald Mann, known as "King" and "Duke" respectively, acquired the TSR in 1911 and began an ambitious expansion program. A line to from Lambton to Guelph was surveyed in 1911–1912, although grading and track-laying was delayed due to the Great War. Plans to carry the line through to Berlin (now Kitchener) were never realized.

(Sir Donald Mann, 1907. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.)

When the TSR Guelph line began operations in 1917, it had only four cars, 101, 104, 105, and 106, the first two being passenger coaches while the latter two also included baggage compartments. Cars 102 and 103 had burned in a fire at the Preston Car Coach Company before they could enter service. By 1918, it was clear that the TSR required more capacity, which was met by the purchase of four used, wooden, open-platform cars from the New York Elevated Company. These old wooden cars made for quite a contrast with the modern, steel cars already on the line.

Two further passenger cars, 107 and 108, were added in the mid 1920s, along with a locomotive and a car-snowplow.

The TSR had a number of interesting features. First of all, it was electric rather than steam powered. Electricity generated at Niagara Falls had recently been brought to much of southwestern Ontario, so it was available for expansive projects such as regional transportation. Power was provided to the TSR line by an overhead system suspended on brackets attached to 35 foot (10.7m) high wooden poles carrying a 25,000 volt AC, three-phase, 25 cycle current.

Power substations were built at intervals along the line to convert this power to DC for the trains. One was constructed in Guelph on Bay Street (now James Street East) although, in the event, it was used as a freight shed instead.

(Intended TSR power substation, 22 James St. E. Courtesy Google Street View. In Guelph, the TSR used the local streetcar tracks from Carden Street, down Gordon Street and then went its own way along James Street East.)

One of the implications of this system was that TSR trains gave a spectacular show in certain weather conditions. Consider a reminiscence by Jack Watkins, who recalls a memorable trip to take in a hockey game:

"I remember going to Georgetown on the thing, one night in the '20s. It was during a sleet storm—you should have seen the fireworks display from the trolley pole! We were going to see Guelph and Georgetown play hockey. We had to crawl from the suburban station to the arena. I can't remember who won the game!"Of course, high-power electrical systems can also be quite dangerous. Norman Paul, TSR electrician at the Georgetown power substation, was electrocuted to death on 28 April 1917 (Acton Free Press, 3 May 1917). He was found unconscious with a skull fracture and both arms badly burned. It seems that he came into contact with a live wire and was hurled violently to the floor. He was rushed to Guelph General Hospital but never recovered.

Another feature of the TSR was that its route was notoriously curvy. Its riders estimated that 1/3 of the route consisted of corners instead of straight lines. The result was that the train lurched perilously from side to side during operation. Indeed, the wide, semi-circular seat at the back of the Main Room was known as the "thrill seat" because of the sideways distance it would travel as the train went along. Passengers remembered the line "fondly" as the "Corkscrew Railway" or the "Seasick Railway" as a result.

The reason for this meandering layout was to economize on land acquisition expenses. Where keeping the track straight meant purchasing expensive property, Mackenzie and Mann opted for cheaper, swervier rights of way. Besides the immediate savings, this strategy may have seemed shrewd since even a somewhat jolty trip on a nicely-appointed train was more comfortable than a trip by horse-and-buggy on the province's rutted and potholed roadways, which was the main alternative for many of the TSR's passengers.

Finally, the TSR had some impressive bridges. The most spectacular was the bridge over the Humber River just west of Lambton Park. It stood at 711 foot long and 86 feet high (217 x 26m). Passage over this vertiginous bridge may have added a giddy touch of vertigo to go with the nausea induced by the rest of the route.

In spite of its initial popularity and considerable virtues, the TSR was not a paying proposition for long. After the Great War, automobiles found ever greater favor with the public, for both recreation and commuting. Busses began to transport groups of people between cities. Governments encouraged this trend through a broad program of road improvements and expansion. No similar effort was made to encourage rail travel, which suffered accordingly.

The TSR began to operate at a deficit in 1921. Perhaps to address this issue, the company began a freight service in 1923. One customer was the Prison Farm, which shipped milk and produce to Toronto over the line. Thus, the TSR truly became a milk run!

Even so, any hopes of profitability faded from view. The TSR ceased operations in 1931. A delegation of Acton residents went to the Canadian National Railway (CNR) office in Toronto at the time to protest the plan. (In 1918, the TSR was acquired by what later became the CNR.) The meeting ended quickly after the complainants admitted that they had made the trip to Toronto by car.

Although the TSR's assets were sold off and its tracks dismantled in the mid-1930s, some reminders of its existence remain in and around the Royal City. At the end of James Street East, past the intended power house, a trail atop the old railway bed leads under the Cutten Club along the south bank of the Eramosa River past Victoria Road and to the old Speedwell stop, near where a concrete bridge led over the river to the Prison Farm. Another section of the old railway bed can be enjoyed at the Smith Property Loop nearby in Puslinch, which is available for walking and biking.

Anyone interested in the TSR specially and local railway history generally must also visit the nearby Halton County Radial Railway on Guelph Line. The HCRY has restored trains and facilities from regional railway history and lies on a section of the TSR right-of-way through Halton County. It is open May through October.

Thanks to the Guelph Public Library and Guelph Civic Museums for assistance with research for this post.

I consulted the following sources for this effort:

- Coulman, Donald E. (1991). "By streetcar to Toronto: Commuting from Guelph the electric way," Wellington County History v. 4, pp. 37–48.

- Kennedy, Raymond L. (nd). "Toronto Suburban Railway: Guelph Radial Line."

- Marshall, Sean (2016). "Mapping Toronto’s streetcar network: The age of electric—1891 to 1921"

- Salmon, J.V., et al. (196?). "Rails from the Junction, Part II: The Toronto–Guelph interurban."

- n/a (1981). "Toronto Suburban Railway: 50 years since abandonment," Upper Canada Railway Society Newsletter, n. 382, pp. 3–9.