It is strangely appropriate to find that incineration remains an issue at Goldie Mill. Since the founding of Guelph, fire, along with water and stone, were always at hand there. The site has seen many changes over the years, changes that are not always evident today. Happily, old postcards, maps, and photos can help us to envision how Goldie Mill used to be, especially as it was developed by James Goldie himself.

David Allan (1939, pp. 38–39) notes that the story of Goldie's Mill begins at the founding of Guelph in 1827. David Gilkison, a cousin of John Galt, and Gilkison's partner Captain William Leaden bought the site (for a total of 25 acres) after having failed to obtain the site of Allan's Mill next to the Priory. There, they built a dam and a sawmill. However, the business never made money and the pair discontinued operations in 1829.

It was sold to Captain Henry Strange in 1833. It seems that Strange operated the mill with more success but died in 1845. Besides operating the mill, Strange also built a house at Cardigan and Norwich streets, as related by Tatham (1983, pp. 6–7):

About 1837 Captain Henry Strange built a house on the property and operated the sawmill. The house, a long low building with arched windows and doorways in a latticed porch at the centre front, is well remembered in some photographs (usually with a little dark dog on the lawn!) still in existence, and by a painting which was in the possession of “Alex” Goldie and was given to Riverslea by his widow, Mrs. Marjorie Goldie. This house was occupied by James Goldie and his family from 1868 to 1891 (and was torn down about 1925). Thus this house, often called “Captain Strange’s House,” was home for James and Frances Goldie and their children, Thomas, John, James Owen, and later Roswell, born in Guelph on March 26, 1862, and Lincoln, born in Guelph in 1864. Baby Margaret probably never saw this house, because she was born in Guelph on February 26, 1867, and died two weeks later, on March 11th.Strange Street was named after Captain Strange, comprising the blocks of what is now Dufferin Street from Kerr to Division.

(The "Old Goldie Home" AKA "Captain Strange's House", complete with lawn dog, ca. 1895. Courtesy of Guelph Public Library Archives, item F38-0-14-0-0-126.)

Local potentate and wheeler-dealer Dr. William Clarke, and his partner Dr. Henry Orton, bought the mill from Strange's estate. To the sawmill they added a flour milling operation that they called The Wellington Mill. This frame structure was the first of several structures to occupy the later Goldie Mill site.

Fire destroyed the mill in 1846. Mills of that era were quite prone to fire and burned down with regularity. So, this event was no surprise. However, the blaze may have been more than a simple accident. As Stephen Thorning has explained, Dr. Clarke was an unreconstructed Protestant who had engendered more than a little contempt from local Catholics during the heated religious conflict of the time. As Justice of the Peace, Dr. Clarke could make life difficult for those whose religion he looked down upon. So, the blaze that consumed his mill may have been sparked by the religious friction of the era.

A determined man, Dr. Clarke bought out his partner's share in the mill privilege and built a new mill in 1850, which he called The People's Mill. This time, Dr. Clarke had the building made from stone, at least some of which was quarried on the property itself.

Over the next few years, the property went through a succession of hands, until it was leased to Charles Whitelaw, a successful businessman from Paris who operated several mills in the Grand River valley, among other concerns. Whitelaw, it seemed, had the touch and the mill apparently operated at a profit.

However, fire returned again on 8 June 1864. Although some of the stores and equipment, and the cooperage across the river, were saved, the mill was a total loss. Stephen Thorning noted that suspicion fell on local cooper Bernard Kelly, who had threatened to burn down the mill before because he did not get orders for barrels from Whitelaw. The coroner's inquest found the the blaze was indeed arson but deemed that there was not sufficient evidence to accuse anyone in particular. Even so, Kelly was convicted in the court of public opinion and hastily left town.

On 8 June 1866, the property was bought for $15,000 by James Goldie. In 1860, Goldie had built the Speedvale Mill further upstream, at the current site of the Speedvale Fire Station. He sold his old place of business and undertook rebuilding and expansion of the People's Mill. It would remain in his hands for 46 years and duly become the "Goldie Mill".

A good idea of what the area looked like during Goldie's tenure can be gained from the 1881 Wellington County Atlas. Because of the dam just upstream of the Goldie Mill, the reservoir made the Speed River much wider there than it is today. Here, I have superimposed part of the town map on a portion of the Google map of the area as it is now. I have outlined the banks of the river in solid lines and the bridges in dashed lines.

Bridges are represented by dashed lines. The parallel dashed lines in the center of the picture represent the dam, which was also used as a foot crossing. The black block to its left is the location of the original sawmill. On the west bank, the reservoir covered the wooded slope that exists there today. Note that a "Victoria Street" was on the survey through the middle of what is now Herb Markle Park. Of course, the street was never built. On the east bank, the reservoir covered most of what is now Joseph Wolfond Park East, upstream from the foot of Derry Street.

Four postcards record views of Goldie Mill. The first one (labelled "1" on the map above) was taken on the west bank of the Speed downstream from the mill. Although the caption identifies the subject as "Goldie's bridge", the bridge in view is clearly what is now called the Norwich Street bridge. Goldie Mill, with its ninety-foot chimney, built in 1885 and which still remains, can be seen peeking over the treetops on the left-hand side, a hint of what is to come.

The building on the right is what was then a storage house of the Canada Ingot Iron Culvert Co. (demolished in 1927). This card is a "bookmark" card, published by Rumsey & Co., Toronto, of a photo taken with a panoramic camera.

The second postcard was taken from the east bank upstream of the Norwich Street bridge (labelled "2" on the map above). The mill buildings can be clearly seen on the left-hand side of the picture. The top of the distinctive chimney is clearly visible behind the other structures. Beneath lies a spit or island separating the Speed on the right from the tail race on the left.

Although the mill is an industrial site, it is presented in the background, framed by water and foliage almost as if it were a picturesque temple discovered on a trek along an Arcadian river.

The third picture (taken from the point labelled "3" on the map above) was taken from beside the tail race and next to the Speed River. It looks northwards to the back of the dam.

There is more tension in this picture. The ground is strewn with chunks of broken limestone, lying around like the remnants of an explosion or quarrying operation. The dam in the background is straining to hold back the waters of the mill pond beyond, without complete success. This card was printed by Warwick Bro’s & Rutter of Toronto.

The fourth picture (taken from the point labelled "4" on the map above) shows the mill pond itself from the north looking southeast. The steeple of St. George's Anglican Church can be seen in the center background. Goldie Mill and its tall chimney can be seen to the right. Today, this spot would be not far south of Riverslea, where the Goldie family then lived, today on the Homewood grounds. The Speed is now much narrower at this point and both banks are thickly wooded.

Near the opposite shore there are two swans in the water. It seems as though they are approaching a man on the bank, who may be moving to feed them. A small boat lies tied up nearby, its stern dragged downstream by the current. This postcard was printed by the Pugh Mfg. Co. of Toronto.

James Goldie acquired two white swans in 1888 to add to his menagerie. His estate was renowned for its gardens. Goldie's father had been a globetrotting botanist and assembled a botanical collection for the Tsar at St. Petersburg. The apple did not fall far from the tree. Goldie Jr.'s gardens contained hundreds of exotic flowers, shrubs, and trees. Visitors came from far and wide to see them.

Goldie's menagerie included many exotic birds, both "preserved" and alive. The latter included Egyptian geese, a Sandhill crane, English, Golden, and Silver pheasants, and the two swans. He also imported English sparrows, some of which he released and some of which he kept in a cage. James Gay, a local man who styled himself the Poet Laureate of Canada, wrote the following poem about them ("Canada's poet" 1884):

On the sparrowsBesides swans, youths liked to swim in the mill pond and places nearby in summertime. There was an old quarry pit at the site known as Kate's hole (for reasons unknown to me), as recollected by Fred Dyson (Mercury, 8 May 1948):

Mr. Goldie’s sparrows, quite a number, returned to James Gay,

He feeds them with small wheat every day,

About eight in the morning, you can see them fly around

To feed on the wheat laid out for them on the ground.

This friend to sparrows, he takes much delight,

To hear their little warblings from morning to night;

All are made welcome as the flowers in May,

Not one shall fall to the ground by the hands of James Gay.

If Mr. Goldie could hear their prattling ways,

He would send them some small wheat every day,

So between the miller and the poet too,

Those little birds are sure to do.

About four they take flight,

If they could speak, they would say thank you and good-night.

Among the real old timers expressing interest in tales of the old town is Fred Dyson, who, at 87, can look back pretty far. Explaining the origin of Kate’s hole down by the spur line at the old Goldie Mill, he said it was the quarrying of stone there for the mill dam that made it a favorite resort for swimmers. The spur line ran right into the mill property.That swimming there in those days was clothing-optional is confirmed wistfully by another old-timer, James Ritchie (Mercury, 1 May 1948):

Who among Guelph’s real old-timers does not remember Crib’s hole, near Russell Daly’s present home? Or Fraser’s hard by the Sterling Rubber Company’s plant, or the staircase near the old Goldie’s Mill? ... These are among many others inseparable from old swimmin’ hole memories. No swimming in the nude anywhere these days. If the boys try it they will be chased away, no matter how far they are from the city.O tempora, O mores!

The Speed could be dangerous as well as beautiful and fun. Spring floods often threatened the dam. Indeed, it was swept away by floods in the springtime of 1873 and 1929.

In addition, girls and boys drowned in the pond alarmingly often, e.g., (Northern Advance, 12 June 1890):

Mrs. Henry Ching, of Toronto, who is on a visit to friends in Guelph, lost her five-year-old boy by drowning on the 5th inst. The little fellow fell into the river while throwing stones into the water from the bank. The river is very high with the recent heavy rains, and he was quickly carried over the dam at Goldie’s mill. The body was recovered in a few minutes, but life was extinct.In the winter, the pond froze over and made for a useful expanse of ice. Guelphites went there for skating and curling. The ice itself was also harvested by Mr. T.P. Carter of Carter's Ice Company, who handled about 2,000 tons of ice annually from his ice houses on Essex Street (Industrial number, 1908). There was also an ice house on the west bank of the Speed upstream of the mill (in the backyard of 165 Cardigan Street today), perhaps for the use of James Goldie himself.

Perhaps the weirdest incident connected with the Goldie Mill pond occurred when it was frozen over. A Mr. Leslie, while walking home at noon hour by the Mill one day, found a green fedora with no band and a worn overcoat lying on the ground beside the ice. In a pocket was a peculiar note (Mercury, 11 Dec 1922):

This seems the only way out. If ‘F’ had been here it might have been different. Good-bye. X.—J.B.The note suggested a suicide. Yet, there was no hole in the ice nearby. No amount of searching and dragging the river or mill race produced a body. Perhaps the whole thing was a prank. Either way, the identity and fate of J.B. remains a mystery to this day.

Goldie remained by the Mill and its pond. Around 1885, he purchased Rosehurst across the river from Dr. Clarke's estate. This grand house stood on the Delhi hill and had a beautiful view of the pond. James's son Thomas and his family moved in. (There is a lovely photo of Rosehurst taken from across the pond, Tatham 1983, p. 9. However, I cannot locate the source.)

James Goldie built Riverslea for himself in 1890–91. It stood somewhat apart from its setting, being made of brown stone imported from New York State (Tatham 1983). However, it was still sited near the east shore of the mill pond with a good view of the Speed and Goldie's Mill downstream. Like his mill, James Goldie never left the river.

The mill prospered. After he took over, Goldie rebuilt the mill larger than before. He also added a substantial cooperage across the river. A rough wooden bridge connected the two. Storage areas and an elevator were added also. See the map below.

Here, I have superimposed a portion of the Fire Insurance map of 1911 on a Google satellite view of the mill and vicinity. As President of the Wellington Mutual Fire Insurance Company, James Goldie would have been familiar with this map.

Just to the left of the mill, is a building shaped like a sideways "I", labelled "A. Office". As mentioned above, the Great Western Railway built a spur line down the Speed to Cardigan Street to serve the Royal City as a new passenger train station ("Guelph railroads", Keleher 1995, p. 59). It opened for business on 16 February 1882 but proved to be a flop and closed six months later. In 1884, Goldie bought the building and moved it next to his mill, where it appears on the map, to serve as office space.

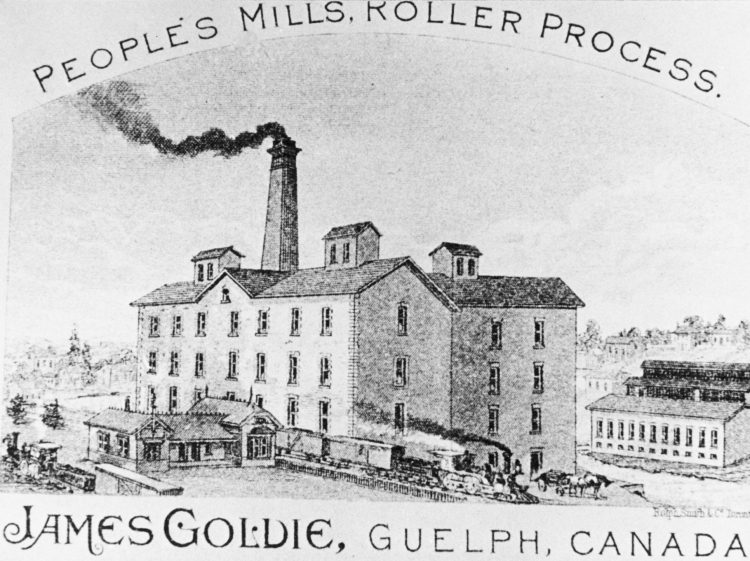

The building can be seen on the left in the cute drawing below.

In 1888, the Guelph Junction Railway was built and a siding laid to Goldie's Mill, which is also visible in the map. As a result, wheat and flour at the mill were no longer transported by horse. This change was important since Goldie increasingly had to buy wheat from western Canada in order to keep the mill profitable.

The office was torn down around 1920. Today, the site is the location of the Guelph Youth Music Centre, constructed in 1995–2001, from a storeroom built in place of the office. The spur line was later torn up and became the Spurline Trail.

As more land in its watershed was cleared, the force of the flow of the Speed diminished. As a result, Goldie added a steam engine to pick up the slack. In 1910, electrical engines were furnished instead, supplied by a power substation dedicated to the mill. The electricity was generated at Niagara Falls. So, the mill ran on power from a river over 120km away rather than on power from Speed, which flowed right beneath it.

James Goldie died on 4 Nov 1912. The mill afterwards passed through many hands. In 1918, the mill was bought by F.K. Morrow, investor and owner of the Morrow Cereal Co. In 1926, the Standard Milling company took over, followed by the Pratt Food Company in 1930.

Time and tide chipped away at the mill and its grounds. Milling operations ceased soon after yet another spring flood wrecked the dam in 1929. The mill became a warehouse with its buildings used mainly for storage. On 24 February 1953, fire returned in the form of a spectacular blaze that destroyed the original milling, shipping, and boiler rooms.

The mill was then slated for demolition but the City and the Grand River Conservation Authority intervened. The remaining stone structures were stabilized and were turned into a picturesque folly. Fittingly, the park was named Goldie Mill Park, still bearing the name of the man who had shaped the place more than anyone else, so many decades before.