Every point in Canada and the United States where the old girls and boys have settled has been deflated of ex-Guelphites, and they may be found here, for this was the first day of the celebration in honor of former residents. How many thousands of visitors there are here it would not be possible to compute, but Mayor John Newstead said this was the biggest day in Guelph that he could remember. The visitors and citizens ranged at will all over the city and through the civic buildings and homes; in fact, in the Exhibition Park, the chief point of interest, they roamed in such numbers that it was almost impossible for one to make a way through the crowd.What occasioned this invasion? It was Guelph's Old Home Week, 1908. (Frank Rollins, Governor of New Hampshire 1899–1901. Courtesy of Wikipedia.org.)

As explained in my previous post about Guelph's Old Home Week 1913, the festival got it's start in New Hampshire in 1899. Governor Frank Rollins instituted a week long, state-wide wing-ding with a number of objectives, the principal ones being to assert the status of northern New England as the essential component of the region, and to stimulate a burgeoning tourist industry there.

Brown (1997) points out that migration of residents away from rural, northern New England for the big cities of Boston, etc., or points west, had left the area somewhat detached from the rest of the region and country, leaving it with a reputation as a backwater. A nostalgic mass return of former resident to the "Old Home" would reconfirm its importance and, more generally, the role of rural life that it exemplified as an antidote to the moral and cultural environment (Rollins would say "decline") associated with city living.

At the same time, Old Home Week would help to establish rural New England as a recreational destination for big city folks and their money. With agricultural productivity in relative decline, a new source of income would be welcome and, Rollins thought, tourism was it.

New Hampshire's 1899 Old Home Week was a smashing success and the idea spread like wildfire throughout neighbouring regions, including the Maritimes, Quebec, and Ontario. Soon, the President of the Canadian Club of Boston wrote a letter to the editor of The Globe (15 June 1901) urging that Canada get in on the act and assuring officials that Ontarians abroad would relish the chance to revisit their old haunts.

The idea of a province-wide (or nation-wide) Old Home Week understandably proved too unwieldy but individual cities soon got in on the act. By 1905 (Evening Mercury, 25 August), locals were writing letters to Guelph newspapers reporting on the Old Home Weeks of nearby towns and cities. Not to be left behind, the powers-that-be in the Royal City kicked the idea around.

(Detail of "Guelph's Old Home Week Executive Committee," from "The Royal City of Canada, Guelph and Her Industries / Souvenir Industrial Number of the Evening Mercury of Guelph, Canada." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 1974.15.7.)In 1907, talk turned into action. An Old Home Week committee was formed and planning began (Mercury, 14 September). A gaggle of subcommittees were formed to handle the challenging task, including Finance, Transportation, Decoration, Publicity, Sports, Music, Reception, and Parade. Dates were set for the civic holiday week of the next year: August 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, 1908.

Various postcards were created for residents to send out as invitations. This postcard provides a helpful form with blanks to fill in and even a picture of someone doing so, just to be clear. The invitee is "Old Pal James," who is identified on the back as Jas. Cowan of Grimsby. The message on the back reads:Oh I wish you were here now. You could work day and night, the electricians are so busy for Old Home Week. How long will you you be down then. I might slide down to see you. However will expect [you] Old Home Week.Electrians were indeed busy, preparing to light the Royal City up like never before. This "Welcome Old Boys" cards was another popular publicity item, also demonstrating the male orientation of the event. However, the Old Girls were welcome too, as demonstrated by the message:

Guelph, July 12/08 // Dear Amabel. how are you today and have you completely recovered[?] be sure and come up for old home week and we’ll sleep outside in a tent. We expect to have a great time. Guelph is buying up all the flags and bunting in Ontario[.] Lots of fireworks too. Bye Bye Cousin HeldaBoth the above postcards are stamped "Daly's // Guelph, Ont." on the back, likely meaning they were sold at Daly's News and Cigar store on Wyndham street.

One of the early concerns was trying to land a prominent figure to help attract visitors. Initially, it was hoped that the Prince of Wales (later George V) might drop in. HRH would be in the country at the time and he was a Guelphite—well, a member of the house of Guelph after whom the city was named. Alas, it was not to be: The King's secretary politely informed the Committee that the Prince's tour would be confined to Quebec.

("Rear Admiral Charles E. Kingsmill (1855–1935), in naval uniform, ca. 1908." Courtesy of Wellington County Museum and Archives, A2002.54, ph. 16831.)However, the Committee got a positive reply from another prominent former Guelphite, Admiral Charles Kingsmill. Kingsmill was born and raised in the Royal City but left age the tender age of 14 to join the Royal Navy. To make a long story short, he served in every corner of the British Empire and climbed the ranks right into the senior echelons. In 1906, he was captain of the battleship Dominion, named for the Dominion of Canada and sent there on a tour to show the flag. The ship ran aground during the tour, resulting in a reprimand for Kingsmill. Even so, he was appointed a Rear Admiral in 1908 and was tapped by the Canadian government with the (unenviable) task of organizing a Canadian navy. In brief, Kingsmill was about as well-known and highly-regarded figure as was likely to attend Old Home Week. One can only imagine the joy with which the organizers received his acceptance of their invitation.

Besides having a star attraction, Old Home Week organizers needed to assist thousands of former Guelphites and well-wishers in making their way to the Royal City. Associations of ex-Guelph people were formed in cities throughout Canada and the United States. Negotiations with the railways resulted in special trains that brought people hence to their old haunts. One of the largest such associations was the ex-Guelphites Association of Toronto, which held meetings and publicized the event in the Queen City. This connection was much assisted and cultivated by the Guelph Committee. Other cities where ex-Guelphites formed associations for the event included Edmonton, Calgary, Regina, Winnipeg, Vancouver, Detroit, and Cleveland.

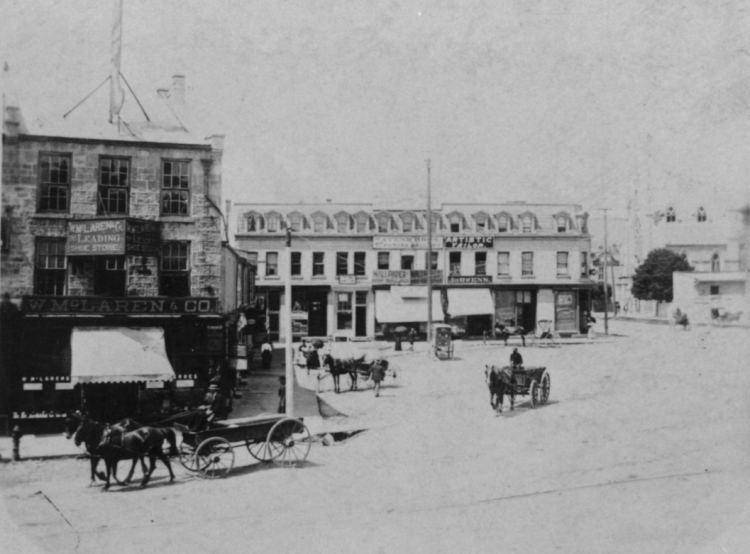

By mid-July, the effort to dress the city up for the event was in full swing. Naturally, there would be banners and bunting of all description on display. Most exciting was the plan to illuminate Wyndham street from end-to-end with electric lights. Since the power grid drawing juice from Niagara Falls did not yet exist, Guelph had to look to the output of its own generators. Representatives of the Light and Power company surveyed local businessess to determine their requirements and to identify whose power could be cut off: Given the system's limitations, bathing downtown in electric light would mean plunging other city sectors into darkness for the duration (Mercury, 18 July 1908).

(The subtitle of this article is a hoot: "Electric fluild to be conserved." Was this really a reference to the already-outdated fluid theory of electricity? Or, was it simply an expression, like "turning on the juice" is today?)

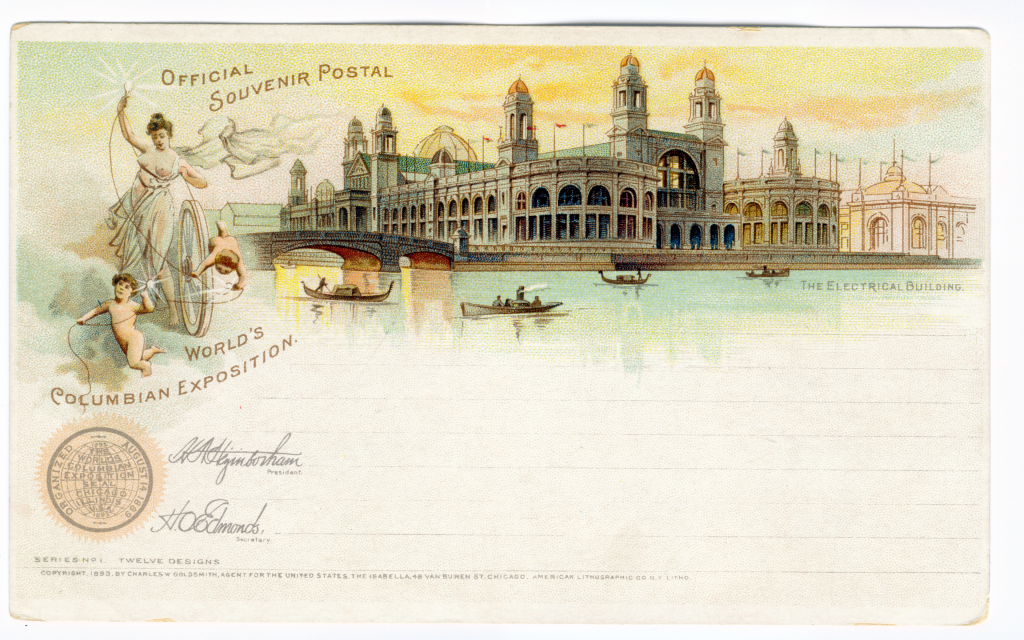

(Souvenir postcard of The Electrical Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. Courtesy of the Chicago Postcard Museum.)Nye (2022) explains that illuminations were very signficant to American cities. In days of yore, torchlight processions and the like were hallmarks of special celebrations and elite occasions. With the advent of gas and then electric lighting, the scope of illuminations to demarcate special places and events increased. For example, The World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 was lit up prodigiously with electric lighting and featured a whole Electricity Building dedicated to the technology's bright future.

The delight experienced by Guelphites with their own electric promenade was palpable. The Guelph Musical Society Band was engaged to play a concert on the night of 24 July during the time the illumination was first tested. A large crowd gathered in the street for the final test on 1 August.

Finally, the carnival of Old Home Week commenced. Decorations had been finalized, accommodations found, grand stands, tents, and light stands erected. Trains arrived at the stations, disgorging hundreds of visitors before heading off to bring more.

A typical day during the celebration began with dignitaries meeting trains of special visitors downtown, requiring official greetings along with speeches and music for the VIPs. An afternoon parade would lead celebrants from the (old) City Hall, up Wyndham, Woolwich, and London streets to the Exhibition Park. There would be a program of events centered on a given theme, held in the fields in the northern sector of the Park. Visitors also had the option of enjoying the midway and sideshows featured in southern area. These areas were fenced off and general admission was $1. After the official festivities concluded, another parade led those so inclined back downtown, perhaps to find their lodgings or their trains back home.

(Real photo postcard view of Lower Wyndham street as seen from the old City Hall. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 2014.84.460.)Naturally, parades featured performances by musical bands. Guelph's Musical Society Band was consistently present but bands from home-comers' cities also took part. For example, on American Day (5 August), the Marine Band of Detroit led the parade, with the stars and stripes out front.

(Real photo postcard view of Lower Wyndham street looking towards St. George's Square. Interestingly, this postcard was sent through the mail in 1915.)The day of 5 August featured burlesque bands. Perhaps the most memorable was the "Blea Rube Band" of Toronto, which performed a "Kiltie burlesque" (Mercury, 6 August):

Yesterday they appeared in Highland costume very cleverly burlesqued and they used instruments on which they imitated the old Highland bagpipes in a style which would have deceived the best bred Scotsman that ever crossed the pond from the land of the heather. In addition they had painted themselves in the most grotesque manner, with heads and faces on their knees, etc.The local favorite was by far "Long Joe" ("alias Madam Le Haut"), local man Joe Lawrence, who sported a parasol and fashionable Parisian gown and who stood out at nearly 7 feet tall. (Real photo postcard of "Long Joe" Lawrence in a white dress with parasol, parading through St. George's Square. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Musuems 2009.3.1. The message on the back states, "This is the only one I have got left of Guelph Old Home week procession[.] it is a man standing seven feet in a lady dress representing a firm from Toronto" )

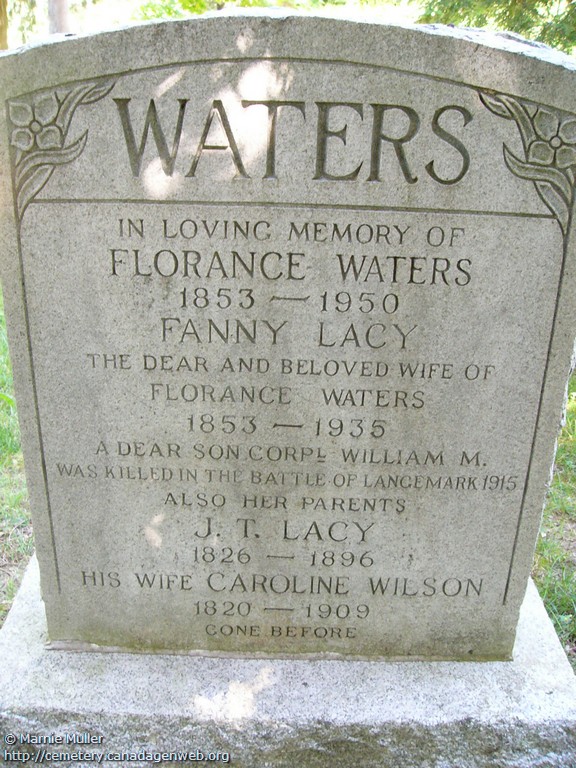

One special feature of the 3 August parade was the appearance of a number of Guelph old-timers (Globe, 4 August). A yoke of four oxen carrying a load of wheat was driven by Mr. Wm. Healey, "who remembers the earliest days of the Guelph market." The wagon was itself an old relic, built 62 years previously and used by the Gow family of Fergus to move wheat to Guelph market square (Mercury, 1 August).

(Real photo postcard, "Souvenir, Old Home Week, Guelph, 1908. In a similar card, the oxen are identified as Tom and Jerry.)Naturally, sporting events featured prominently in the afternoons. There were competitions in lawn bowling, lacrosse, horse racing, and track and field. The most anticipated event was the baseball game between Eastern League rivals the Toronto Maple Leafs and the Jersey City Skeeters.

The game itself turned out poorly for the Canadian fans, with the Maple Leafs receiving a drubbing at the bats of the American team (Globe, 5 August):

What the lowly Skeeters did to the champion Maple Leafs here to-day was cruel and almost criminal, and before a crowd of 8,000 Old Home week celebrants at that. The Mosquitoes—for it was an occasion which called for some politeness—thumped, hammered and slugged their way around the bases fourteen times in the seven innings before darkness mercifully put an end to the slaughter.The final score was 14–1.

On the bright side, the Maple Leaf's one run was a homer off the bat of Jimmie Cockman, a Guelph Old Boy! Cockman had been born and raised in Guelph and excelled in baseball to the extent that he had a solid career with many professional teams. As captain, Cockman led the Milwaukee Creams to the top of the Western League in 1903. In 1905, he was seconded to the New York Yankees by his Newark International League team, making him one of the few Canadians of the era to play in the American major leagues. He retired and returned to Guelph in 1912 but coached the Guelph Maple Leafs in their championship run in 1921.

("James Cockman, Guelph's well-known professional player," The Canadian Century, v. 4, n. 13, 1911.)At Cockman's first at-bat in the second inning, play was suspended and a brief ceremony held to honor the Royal City's famous son (Mercury, 5 August):

The players of both teams formed a semi-circle around the popular third baseman, while Mr. Downey [local M.P.P.] acted as spokesman. In a few words, Mr. Downey stated that the many admirerers of Jimmie in the city had considered this a suitable time to show their esteem and admiration for that popular and very efficient player. He also referred to the fact that Guelph had been the birthplace of baseball in Canada.(Real photo postcard of St. George's Square from the middle of Lower Wyndham street. This image was the most commonly reproduced postcard of Old Home Week.) (Real photo postcard view from the Post office/Customs house of a parade marching through St. George's Square. Note Joe Lawrence in a dress in the foreground and a marching band following him. A hand-written message on the front states, "scenes during Old Home week on main street, Guelph".)

Mr. Morris then presented Mr. Cockman with a diamond ring, and the crowd gave three cheers and a tiger.

Another signal event for Old Home Week was the military tattoo. On the evening of August 5, crowds of people packed into the grandstands in Exhibition park to see the spectacle. The conditions were excellent (Mercury, 6 August):

A dark, still night, not very warm, with a gentle breeze blowing steadily. The colored lights placed along the fence and the edge of the track cast a lurid glow over the track, throwing into relief the soldiers and bandsmen as they marched past, and sillouetting darkly the crowd in the background.The bands stood poised at the north end of the park. At the signal, the Guelph band marched forth, down the track and past the grand stands, under the baton of Drum-Major Fairburn. The hometown crowd cheered with excitement. ("Captain Walter Clark," ca. 1900, veteran of the Crimean War and drill instructor of the Guelph Cadets. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, Grundy 3.)

Next followed the bands from Preston, Berlin (now Kitchener), and Goderich. Following them were the formations of troops and then the cadets, under the direction of Captain Walter Clark.

Following this was a prodigous fireworks display. At first, sparkling lights produced a portrait of King Edward, accompanied by the national anthem played by bands and three volleys fired by the Wellington Riflemen. Then followed a portrait of Theodore Roosevelt, which prompted an ovation.

The finale comprised an all-in burst of colour and noise that took the crowd's (and the reporter's) breath away:

Every variety of rocket was fired off in rapid succession. The air was literally full with glowing, flashing, rapidly-changing colors. There was a constant succession of glowing lights, bold color breaking into myriad [displays of] many colors, jumping rockets whirled and twisted with eccentric irregularity. “Maxim” or repeating rockets, fiery clouds which seemed charged with shifting rainbows. It was a gorgeous pyrotechnic display of such magnitude that the crowd literally held its breath while it lasted.The bands followed up with a few more selections and paraded back to downtown, followed by many of the excited specators. (Real photo postcard scene of an Old Home Week parade in St. George's square, conveying some of the excitement at street level.)

At the south end of the park was a midway, featuring attractions such as a Ferris Wheel, Merry-Go-Round, Electric Theatre, Fairies in the World, Coney Island at Night, Darkness and Dawn, etc. In a tent labelled "The Train Wreckers," one could see moving pictures!

The train wreckers was the title of a hit short film from the Edison Company, 1905. It features one of the few actual cases on film of villians trying to do away with a girl by leaving her on railroad tracks. Watch for the trick photography during the rescue scene!

Naturally, there was a so-called freak show. One freak performer was "Rattlesnake Joe," AKA Mr. J.H. Wilson, who was immune to reptile venom. His act was to handle a menagerie of poisonous snakes, which he allowed to bite him on the arms, chest and even his tongue (Mercury, 6 August)! Amazingly, he seemed none the worse for wear.

Then there were two "fat boys," weighing over 600 lbs between them, who engaged in boxing matches, using gloves. There were also three snakes, of a combined length of more than 100 ft., an untameable ape, and a two-headed fetus preserved in alcohol. The curious could attend lectures on any or all of these subjects.

Special performers were also employed to please the crowd between the main attractions. For example, there was the Dare Devil Dash, in which Professor Zavaro peddled his bicycle madly down a 100 ft. ramp, vaulted a wide chasm, turned around in mid-air and, leaping from his ride, dived into a vat of water. This is a feat beyond most university professors. Was Zavaro on sabbatical?

Perhaps from the same institution came Professor Tardini, the balloonist. His vocation was staging balloon ascensions accompanied by fireworks displays aloft. After this, Tardini would descend back to mother earth using a parachute.

(A real photo postcard featuring a man and woman looking at the camera through a cut-out backdrop of a balloon with gondola. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 1986.18.153. This appears to be an homage to Professor Tardini's balloon. It was likely taken in a photographer's studio in town.)Tardini's balloon had difficulty in rising to the occasion. The wind was too high in the afternoon of 5 August to permit him to fill his gas bag. However, conditions improved and he was able to ascend and provide an aerial fireworks show that evening. An intriguing aspect of Tardini's setup was that his balloon was filled with "real gas" rather than hot air. If this means hydrogen, then the Professor was even more brave—or more foolish—than he seems at first. I can only think he was not a professor of chemistry.

Most impressive were the performances of the Kishizuna Japanese acrobatic troupe. Their performance is not described in detail but it was praised as "easily the best attraction on the grounds and has proven well worth the money expended by the committee" (Mercury, 6 August).

("Kishizuna Imperial Japanese Troupe," ca. 1910, postcard publisher unknown. Courtesy of "aboveall" via HipPostcard.com")No detailed account of the Kishizuna act is given but it may have featured elements like those recorded in a short film by "Japanese Acrobats" (1913): ("Japanese Acrobats," 1913. Courtesy of the British Film Institute National Archive, via Friends of the British Film Institute.)

One of the more intriguing aspects of accounts of the 1908 Old Home Week were descriptions of how orderly it was. One might expect a week-long wing-ding to be the occasion of some overzealous revelry. That was not the Police Magistrate's opinion, however. "I am agreeably surprised and pleased with the manner in which the large concourse of people have conducted themselves in the city during the Old Home Week," Justice Saunders remarked (Mercury, 6 August).

There were not infrequent cases of drunkness, of course, but these were handled discretely by police, who put simply put inebriated celebrants in holding cells until they sobered up, at which point they were decanted. So, it seems that good order was kept in part by bending the usual concept of what was considered orderly.

("Ancient Order of Pole Climbers - Old Home Week Ribbon." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 2014.33.20.)It seems the police were more interested in assaults and thefts, of which there were not many. The only issue on this count was a young man who threatened to shoot someone and was found in possession of a loaded revolver. As this person had no license to carry a firearm in the city, he was fined $8.50 or one month in jail.

Still, the police blotter could hardly convey the experience of being on Wyndham street during the carnival. The account of the Mercury's own reporter must be our guide ("Confusion reinged," 6 August):

Bedlam let loose could not present more madmen than did Wyndham street last night after the return of Ralph Humphries’ “Illustrated” parade from the park. The old town, sober, quiet, old Guelph aroused itself in earnest. Everybody was just crazy with joy, falling over themselves and everybody else in their efforts to have a good time—and they were having it, too. There has never been anything the likes of it before in the old burg, and visitors from afar would last night have had recourse to the old saying that “a thing must be seen to be believed.” To describe anything that happened would be an impossibility. Everything that could happen occurred, and it was occurring all the time. From end to end the street was filled with a joyous, yelling jovial crowd of the best humored people ever gathered together. Anything went with crowd, and everything was taken in the spirit in which it was given with freedom and good spirit.Magistrate Saunders had said that the orderly conduct of citizens during the week "would convince those who had been opposed to the reunion that it was not a week of drinking and debauchery." Were they convinced?

At ten o’clock the fun was officially commenced, and The Mercury still awaits reports as to when it was concluded. No matter how late or how early it was when people left the town, they had the opinion that they were missing something. At two o’clock this morning the lights were put out, but the fun did not discontinue until a long time after that. Throughout the several hours of fun there was not the least let-up at any time. Everybody appeared to be tireless, and the mob rushed from end to end of the street, howling, yelling, cheering and throwing everything at everybody “without fear or favor.”

Of all the games of the street last night, there was nothing so popular with the mob as the merry go round. To the majority of the readers there is no need to explain the principle of the game. They have experienced it, and know what it is. But it may be explained that the merry go round consists of the old time bull in the ring game. The innocent cause of the trouble, who may be standing on the street with his lady friends, is suddenly surrounded by a bunch of hooting, yelling lunatics and for the next few minutes they have the opinion that they are in the centre of a cyclone. But the storm soon passes to another quarter of the street, and no one is the worse for the experience.

Another popular form of lunacy last night was the flying wedge, which worked on the principle of the rotary snow plow, and had the effect of clearing the street with a rapidity that would have done credit to the Guelph police force. At the ends it worked with the same effect as crack-the-whip and woe to the man who got in the way.

Half a dozen wagon trucks, etc., put in their appearance on the street at different times and were pulled from one end to the other in great style. One of these was put into intentional collision with the wagon of the peanut man, who thereupon decided to make for safer quarters, but the crowd were after him, and before he got half way across the square wagon, charcoal, peanuts and fire were distributed over the square in a very impartial manner.

The fountain on St. George’s Square was the Mecca of many of the hoodlums. More than one was ducked. Some were thrown in bodily, while one unfortunate who was reposing on the stone coping was compelled to turn a graceful back somersault into the tank.

Apparently under the delusion that he was in the holy water of the Ganges, a local tonsorial artist entered the dampened arena, and with the water to his knees commenced a parade in which he was given the undisputed proprietorship of the parade ground. He seemed to enjoy it immensely, and kept not all the pleasure to himself. He had a sponge which he attached to a string and by its aid was very successful in distributing shower baths upon the crowd.

Ald. Humphries, the chairman de parades, was the hero of the night, and his appearance for the midnight parade was the signal for a general ovation. Everybody cheered for Humphries. He was the idol of the hour. On Upper Wyndham street despite considerable damage to his wearing apparel, he was hoisted to the shoulders of some of the enthusiastic ones and carried all the way down the street.

No city could operate under such conditions for very long. By the evening of 7 August, the festivities wound down and Guelph put her sober countenance back on. People flocked to the train stations to catch trains out of town. Decorations were removed and special lighting turned off. A number of people attended the final performance of the Kishizuna Troupe and took in "The streets of Cairo," curious to see a sideshow deemed objectionable by some of their fellow citizens. This piece was a vignette about a young girl on the mean streets of Cairo and had been composed and performed for the Chicago Columbian Exhibition in 1893, where it was a hit. It featured a belly dance known as the hoochie-koochie, which was probably the most objectionable part. The tune remains one of those old melodies widely recognized today but whose origin most have forgotten.

With these last, few performances over, the tents were taken down and the performers departed for their next gigs. Guelph became its old self. As the Mercury (8 August) put it:

Where on the previous night riots reigned where the air was filled with confetti and talcum powder and funny noises, last night reigned the silence and quietude of a quiet city.Old Home Week 1908 was over. Was it a success? Fiscally, the Reunion Committee expected a small deficit. However, most everyone had had a grand time and were not concerned if the affair did not quite break even.

It is unclear that Guelph had demonstrated the superiority of small town Ontario culture or morals. Nor is it clear that the Royal City had set itself up as a tourist Mecca. Still, citizens could be satisifed that their city had come a long way since its foundation, and that it could put on a blast to compare with those of any of its neighbours.

Already, there was talk of mounting another Old Home Week.

("Guelph Old Home Week souvenir pin." Courtesy Guelph Civic Museums 1978.165.7.)Works consulted for this post include:

- Brown, D. (1997). Inventing New England: Regional tourism in the nineteenth century. Smithsonian Institution.

- Nye, D. E. (2022). American illuminations: urban lighting, 1800–1920. MIT Press.