Eden Mills, a short distance up the Eramosa River from Guelph, has a reputation as a quiet and picturesque rural village. But, it wasn't always so. When Aaron and Daniel Kribs arrived the site on 14 April 1842, it had a good water supply but not much else to recommend it (Mercury, 20 July 1927):

Finding that there was sufficient fall in the bed of the river to raise about eight feet head of water at that place, they proceeded, after building each a shanty, to clear the ground for the mill dam. This required a good deal of courage, for a more dreary or unsightly looking place could not be found in the whole township, than it was at that date.

Despite the rough nature of the terrain, the availability of water and timber, plus the determination of the brothers, made them press on:

However, the Messrs. Kribs pushed ahead, and by the 1st of October of the same year, had the dam completed, the saw mill running, and a good one it was too, for an old fashioned water mill. Having a good lot of pine trees convenient to the mill, they set to work sawing lumber, and very soon the people found a way to get it out from the place. Although they had only a miserable apology for a road, yet the lumber was taken away as fast as cut, and they did very well that fall and winter.

(Postcard of "Mill pond, Eden Mills," ca. 1955.)

Daniel Kribs was born near Hamilton in 1816 and moved with his family to Eramosa in 1826 (Globe, 6 December 1898). The new mill was evidently the Kribs brothers' chance to make a name for themselves. So, they called their new locale "Kribs Mills" (sometimes spelled "Cribbs Mills").

("Grist Mill," ca. 1923; Courtesy of Guelph Public Library

F38-0-15-0-0-340. These stone buildings replaced the frame mills built by the Kribs.)

Flushed with success, the Kribs brothers added an oatmeal and a grist mill to their enterprise. Unfortunately, this addition proved their undoing. The millwright they hired to construct it did a poor job, resulting in an underpowered mechanism that could grind only a fraction of the capacity required to run at a profit.

The brothers persevered but could not make good their debts.

In the spring of 1846, Adam Lind Argo came to the town and saw an opportunity. He offered the Kribs $5000 for their operation and lands and, although it was only half their investment, they accepted and washed their hands of the operation. Daniel Kribs later moved to Guelph, where he became a court bailiff and a respected member of the community.

Adam Argo was born about 1809 in Foveran, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and immigrated to Canada in 1836. He gained milling experiece in Bridgeport and Preston before striking out on his own. Thanks to his experience and acumen, he was able to remodel the Kribs's mills and keep them running in the black.

Unsurprisingly, Adam chose to rename Kribs Mills and selected "Eden Mills" instead. Various stories are told about his reason for this choice. One story is that the name "Eden" was adopted to help attract interest in the otherwise unappealing locale, rather as Erik the Red choose the name "Greenland" for the icy North Atlantic island he was trying to sell back in frosty Iceland. Another story is that the name "Eden" had a Biblical provenance: Just as the original Adam came from Eden, so this new Adam would return there, in a manner of speaking. Another possibility is that Mr. Argo choose "Eden" in memory of his homeland, where there are a number of places featuring that name, such as Eden Castle in Aberdeenshire.

(Postcard of street scene of Eden Mills, 1905; Courtesy of Wellington County Museum & Archives

A1989.101.)

Whatever the reason, Eden Mills ultimately proved attractive. The Mitchell’s Canada gazeteer of 1864 gives the following description and list of village enterprises, suggesting a thriving community:

Eden Mills, C.W.—A village, situated on the river Speed, in the township of Eramosa, count of Wellington, containing a good female school, three churches and Mechanics’ Institute library with 460 volumes. Distant from Rockwood, a station on the Grand Trunk Railway, 3 miles; Guelph 7 miles. Daily mail. Population 250.

| Antony, Jackson | shoemaker |

| Bardswell, Meshack | retired |

| Boyle, Andrew | blacksmith and wagon maker |

| Burrows, Wm. | shoemaker |

| Cook, Charles | cabinet maker |

| Cook, Frederick | cabinet maker |

| Davidson, John A. | carpenter and builder |

| Davisdon, John A. | collector, land agent, issuer of marriage licenses, commissioner in B.R. conveyancer, &c. |

| Dowrie, David | carpenter |

| Esson, John | builder |

| Fielding, David | grocer |

| Frain, James | wagon maker |

| Harmston & Henderson | builders |

| Harris, John | hotel keeper |

| Hay, John | shoemaker |

| Hortop, Henry | flour mill |

| Jackson, Anthony | general merchant |

| Krase, Greorge | cabinet maker |

| Little, James | miller |

| Malcolm, Mrs. | female school |

| Meadows, Sam’l | postmaster, general merchant, sewing machine agent, and potash manufacturer |

| McDonald, Alex | tailor |

| McDonald, John | cooper |

| Richardson, Ralph | wagon maker |

| Ritchie, William | builder |

| Stewart, Alexander | builder |

| Sullivan, Timothy | blacksmith |

| Watson, Wm. | mail stage proprietor |

| White, James | constable and lime burner |

| White, Thomas | retired |

| Wilson, James | J.P., and oatmeal mill |

| Wilson, Peter | woollen manufacturer |

| Zouart, John | retired |

The sharp-eyed reader will note that Mr. Argo had sold the mill by this time (1850), and relocated to Fergus.

Despite being largely cleared, local trees continued to play a significant role in the village. In 1872, some local men performing statute labour nearby discovered a human skeleton in an advanced state of decay with a flagstone laid across its breast (Mercury, 19 June 1872). They supposed that it was an Indian burial, as it was found under the roots of an old pine tree and must have predated the arrival of settlers. It crumbled to dust on removal.

In 1890, Mrs. William Geddes of Eden Mills was killed in an unfortunate accident involving a tree near the village (Mercury, 31 July 1890). She and her children had gone berrypicking with some friends in Mr. Anstee's swamp. The two parties had just gone their separate ways towards home when the children ran back saying that their mother had been struck by a tree. Her friends hurried to the spot to find that Mrs. Geddes had been killed outright and was lying next to the tree that had felled her.

In 1912, Eden Mills was hooked up to the electrical grid, like many towns in southwestern Ontario, to receive power generated a Niagara Falls. Construction of the Hydro corridors resulted in the felling of many trees, which met with some protest, reflecting a rise in interest in forest conservation advocated by people like Edmund Zavtiz of the Ontario Agricultural College (OAC). In a letter to the editor of the Globe (12 June 1918), J.E. Carter complained of "the great destruction of our beautiful shade trees along our highways by linemen who butcher them." He drew particular attention to "a fine row [of rock maples] near Eden Mills" that had recently suffered this fate. Carter noted that the Ontario Tree-Planting Act limited the powers of linemen to trim roadside trees and urged rural residents to exercise their rights to defend them.

(Postcard of Eden Mills showing General Store and post office, mill, and building located south of mill, 1912; Courtesy of Wellington Museum & Archives,

A1989.66.)

Besides trees, water was a crucial part of Eden Mills early history. Of course, it powered the mills themselves but it also provided opportunities for recreation. In 1843, a party of young men were working on construction of Kribs's grist mill and decided to take a little break from the hot weather in the mill pond. Two of the party, Gerow and Duffield, got in over their heads and disappeared under the water. Daniel Kribs came upon the scene and managed to pull them out. Duffield appeared to be dead but local resident Stephen Ramage applied some "resuscitation techniques" and restored him to life.

Despite this close call, the mill pond continued to be a popular local swimming hole.

(Postcard, "Mill stream, Eden Mills, Ont.," ca. 1955.)

Of course, the mill pond and Eramosa River were popular places for locals to go fishing. So, it was the setting of many fish stories, such as (Globe, 20 July 1886):

An ex-student of the Agricultural College, now employed near Eden Mills, made loud professions of his abilities as a fisherman. Some persons, however, had so little faith in his attainments in this line that they made a wager that a young lady of the neighbourhood could outfish him, he however, to catch six to her one. The result was the young woman caught nine fish, one of which was a trout weighing a pound and a half, while the ex-student caught six shiners [minnows].

Grrl power! It would interesting to know who these fisher folk were. The young man whose angling pretensions were so ignominiously punctured may have been R.A. Ramsay, a local lad who had graduated from the OAC four years earlier.

In the great tradition of the pasttime, local anglers' exploits were always open to question, for example (Mercury, 17 June 1887):

The Rev. J.C. Smith, B.D., and Mr. Geo. Sandilands, manager of the Central Bank, were trout fishing in Eden Mills yesterday. Mr. Sandilands told a glowing story about trout, and trout fishing. The reporter would at any time take Mr. Sandilands’ word for $20,000, but when it comes down to veracity on a fishing expedition it is another matter. Mr. Smith was not seen on the streets to-day, and thus the promised one true fish story of the season is knocked on the head. It is privately whispered, however, that the catch was beautifully small.

Doubtless, more than a few whoppers were fished from the Eramosa at Eden Mills.

As it happens, more than water flowed through Eden Mills. In 1886, following a tip, police officers raided Johnston's Hotel there looking for violations of the Province's new Scott Act (Mercury, 24 December 1886):

Edward Johnston, who keeps a hotel there, was the suspected party. His premises were searched, and underneath the bar in the cellar was found a small still in full working order. The still was erected on the top of a common wood stove, with worm in a cold water tub near by. A considerable quantity of wort in different stages of fermentation was also found, together with distilled spirits. The whole was seized and the wort destroyed. The still and fermenting tuns were brought to Guelph.

Having been caught red-handed, Johnston pleaded guilty and was fined $50.

(Stone hotel building in Eden Mills, 1973; Courtesy of Wellington County Museum & Archives

A1985.110.)

It seems that Johnston learned his lesson. A short time later, we learn of thirsty patrons being turned from the doors of his hotel (Mercury, 4 February 1888):

On Wednesday afternoon, it seems Mr. Arch. Robertson, living near Eden Mills, went home from Guelph with enough liquor to make him quarrelsome. Being refused entrance to Johnston’s hotel in the village, he ran foul of Mr. David Shannon, and in the encounter received a black eye. In the evening he returned with the assistance of James Rouse and William Hillis and visited Shannon’s house. Shannon was called to the door and assaulted by the trio, and had his window and sash broken. Shannon swore out an information and on the three parties appearing before Squire Strange they were fined $20 each, $5 costs each, $3 for the damage done, and bound over to keep the peace for 3 years. The villagers were much annoyed by the unseemly row, and trust that the result of this case may prove a warning to others disorderly disposed.

Unfortunately, it seems that later proprietors of the hotel were not so scrupulous. Joseph Zinger, who kept the hotel in the 1890s, was found guilty of illegally selling liquor on several occasions.

Matters came to a head in 1904 when the Prohibition League of Guelph complained to authorities about lax enforcement by W.S. Cowan, the license inspector for South Wellington. The Inspector, they said, took no action despite numerous complaints made by the League against establishments in Everton and Eden Mills. Indeed, his superiors were unimpressed with Cowan's defence (Globe, 27 February 1904):

The department wrote to him twice about the matter, and he replied that he had made an inspection, and at Eden Mills had confiscated so much liquor as to necessitate a team to take it away. The department decided that he should have known of the open violation long before, and that after such glaring evidence of incapacity there was no alternative but to ask for his resignation. He declined to resign, and the department removed him.

What did the neighbourhood think of a village where the license inspector hauls away a wagonload of illicit liquor and his bosses figure that he isn't trying hard enough?

(Postcard of Eden Mills showing General Store and post office, mill, and buildings located west and south of mill, 1912; Courtesy of Wellington County Museum & Archives

A1989.66.)

Besides wood, flour, and whiskey, Eden Mills was once set to become a petro-town. Apparently, enough oil had been dug up in the vicinity to prompt villagers to form the Oil Company of Eden Mills (Globe, 19 January 1866). Directors were appointed and capital not less that $4,000 was sought. At the inaugural meeting, it was resolved that

the shareholders, owning land at a distance not greater than three miles from Eden Mills, agree to bond their land for oil digging purposes at a royalty of one-eighth of the proceeds of the well, or wells sunk by the Company—said shareholders binding themselves, at the time of taking stock, to hold their lands open for three years for the company for that purpose, and said contract, when executed, to extend to 99 years.

The village was said to be in "a fever of excitement." Test wells were dug and samples sent to Toronto for analysis. Yet, after a year or so, Eden Mills' search for black gold did not pan out and the village never did become the Calgary of South Wellington.

(A forest of oil derricks in Los Angeles, Toluca Street, ca.1895-1901. This failed to materialize in Eden Mills. Courtesy of

Wikimedia Commons.)

One of the challenges for residents of the village was its relative isolation. When the Grand Trunk Railway from Toronto to Guelph was built in 1856, it went through nearby rival Rockwood instead of Eden Mills. So, when the Guelph Junction Railway was proposed in 1886, to connect Guelph to the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) line at Campbellville, residents saw a chance to catch up. After a village conference, Messrs. Laing and Nicol were sent to a meeting of the directors of the new railway to urge them to adopt a route through the village (Mercury, 6 April 1887). They acknowledeged that a route through Eden Mills would be a little longer than the one proposed near Arkell but argued that it would have compensating advantages. Eden Mills was home to many gravel pits that could supply building materials cheaply. It's grist, oatmeal, and shingle mills produced much material that could be shipped from a station in the village, not to mention the plenteous turnips! The directors promised to relay the proposal to Mr. Jennings, the CPR Engineer, though they were not optimistic for its prospects.

As residents contemplated this gloomy news, things suddenly looked up. A navvy, that is, a civil engineering construction worker, soon appeared in the village, equipped with boots, shovel, and spade. Residents inferred that the Junction railway was to grace their village after all! Alas, it was not so and the people of Eden Mills had to deal manfully with their disappoinment (Mercury, 19 April 1887):

The new arrival was received with open arms, but when he avowed, on being questioned, that he knew nothing about the Guelph Junction, he was treated to the cold shoulder, and plainly made to understand that his [ab]sence would be a relief, and if he did not go he would be assisted.

In the end, the CPR decided on the shorter route and Eden Mills was bypassed again.

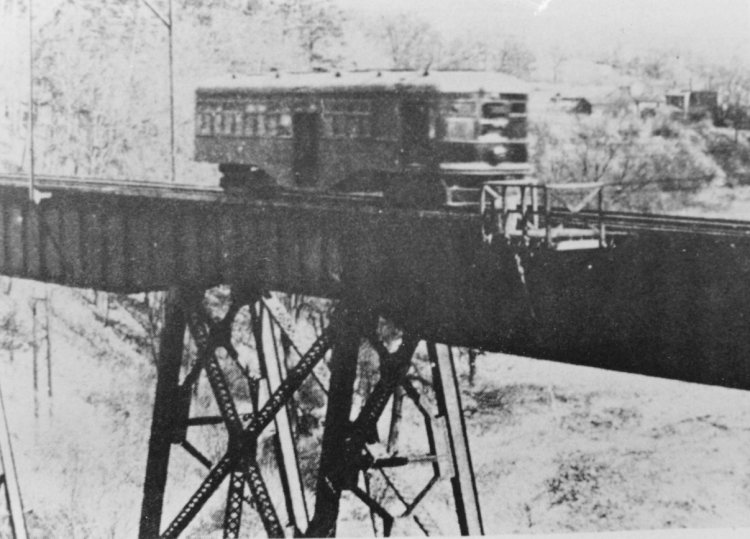

However, the patience of villagers was finally rewarded when the Toronto Suburban Railway (TSR) was built between Toronto and Guelph in 1913–1917. This was made possible by the extension of Hydro power to Eden Mills in 1912. When it became operational in 1917, the TSR enabled residents to ship and receive goods from their local station. In addition, visitors could readily arrive by train to enjoy events such as dances put on in Edgewood Park (later Camp Edgewood). Residents could get to larger centres for their amusement and convenience.

(Oatmeal mill, Eden Mills, ca. 1923; Courtesy of Guelph Public Library

F38-0-15-0-0-341.)

However, by the time the TSR arrived in town, a rival mode of transportation was taking hold, that is, the automobile. At first, cars were largely expensive summer amusements for wealthy urbanites. Early car owners from town would take their vehicles for joyrides through the countryside, spooking the horses and annoying rural residents.

Some residents occasionally lashed out against these urban elites by setting traps for them in the roadways. On one occasion, Mr. Walter Harland Smith, Liberal candidate in Halton County, met with just such an improvised obstacle (Globe, 12 September 1911). He had finished addressing a meeting at Eden Mills and was driving to Campbellville for another when, just near the top of a hill near Brookville, his car crashed into a barricade of logs and stones thrown over the road. He and his two companions were ejected from their auto and badly shaken up, though not seriously injured. However, their car was completely wrecked.

It may be that this attack was directed specifically at Mr. Smith as a form of politial opposition. If so, it nonetheless employed a tactic that was also directed indiscriminately against car operators in rural areas of Ontario, and elsewhere, at the time.

(Map of Eden Mills, 1906; Courtesy of Wellington County Museum & Archives

A1985.110.)

However, by the end of the Great War, car ownership had become more common, including among rural residents. One news story about an unfortunate incident following a wedding in 1919 shows that there were at least two automobiles in Eden Mills by that time (Globe, 24 October 1919):

Death came quite suddenly to-day to Frank Ramshaw, a highly-respected citizen of Eden Mills. In company with Geo. Gordon, he was returning home in a motor car from a wedding.

In another car just behind him were his son and several others, and when about three or four miles from Rockwood this car overturned and went into the ditch. The car ahead stopped, and Mr. Ramshaw got out and went to a nearby farmhouse to secure assistance. He came back only to find that everything was all right and no person hurt.

While he stood there, however, he suddenly fell forward, and almost before anyone could reach him he expired. Death was no doubt due to heart failure brought on by the excitement due to the accident. Mr. Ramshaw was about sixty-five years of age, and was well known. He leaves a wife and several children.

Increasing popularity of private automobiles decreased interest in the TSR, which ran mostly at a deficit and ceased operations in 1931. Sections of it are now operated as trails by

the Guelph Hiking Club, including in the vicinity of Eden Mills.

(Mill pond, Eden Mills; Courtesy of Google Street View.)

Of course, there is much more to the history of Eden Mills, which is perhaps best known today for the Eden Mills Writers Festival. Suffice it to say that, despite initial appearances and a few challenges, Eden Mills did become an attractive and lively locale.

The following works were consulted for this post: