Today, the Heffernan street footbridge stands almost exactly that place, a monument to the Reverend's old commute to work.

("Arthur Palmer, 1874." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.32.2762.)But, the bridge did not come into existence straightforwardly. Indeed, for many years, it was a kind of confabulation, a structure that existed only in the desires of commuters like Rev. Palmer. On land, such "desire lines" are paths worn into the ground by many feet passing by the same route through a park or vacant lot. For example, a wide desire line led across the Johnston Green from the corner of Gordon and College streets to Massey Hall, a route that was recently paved by the University of Guelph.

Of course, you cannot wear lines into a river but people can still yearn for a permanent way across them, a sort of fluid line of desire.

Perhaps the earliest record of this particular desire line comes in the 1855 Palmer Survey map. At this time, the Rev. Palmer had bought up a goodly parcel of land along the north bank of the Speed and up across the ridge of the hill behind. (He was then in the process of building his new residence "Tyrcathlen," now Ker Cavan, on the site.) In a detail of the map, a bridge labelled "proposed bridge" is shown connecting the foot of Grange street with Thorp street on the other side.

(Detail of "Land Survey, Arthur Street Subdivision, 1855;" courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 1981X.221.1.)Proposed by whom? We are not told but the Reverend himself must surely have blessed the plan.

Nothing was done but the desire did not fade. In 1869, a scheme was floated and money pledged to carry it out, with a hearty endoresement from the editor of the Guelph Mercury (7 May 1869):

There is no question as to the desirableness or utility of such a bridge, for it would be of great service to the bulk of the ratepayers living in that section across the river, as well as those residing on the road in rear of the hill on which Archdeacon Palmer’s and Mr. John Horsman’s residences stand.The Archdeacon himself put his money where his mouth was:

Archdeacon Palmer has with great liberality offered to give twelve feet of land from the road to the river bank as an approach to the bridge, and in addition will give $100 subscription towards the construction of the bridge.For reasons they do not explain, the City's Board of Works shot down the idea at their next meeting. It was still a bridge too far. ("St. George's Church, 1874." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, Grundy 60. The first footbridge would be built at this site a few years later.)

Headway was made in 1876 when Heffernan street was created on the north side of the river, right where the bridge was to make land. (The street was named after Thomas Heffernan, a prominent merchant.) Surely, bridging of the river, and thus completion of the street, would be accomplished the next year said a column in the paper (Mercury, 5 December 1876).

("T. Heffernan, n.d." Courtesy of Wellington County Museum and Archives, A1985.110.)This was duly not accomplished. The issue turned on what kind of bridge was to be realized. Some people's desires went as far as a street bridge, which would accommodate general traffic. Others' vision was limited to a footbridge, which would carry only pedestrians. The main difference was price: A full-sized bridge would cost $2,300, while a footbridge would run only $1,500—or even merely $500 for a basic model.

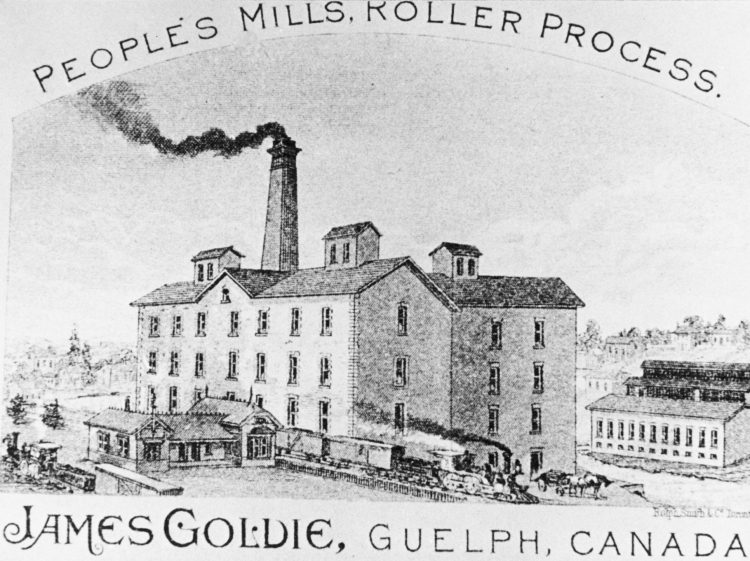

("Goldie's Mill race, ca. 1885." Courtesy of the Guelph Civic Museums, Grundy 225.)There were many footbridges in Guelph. In the main, these were built into dams so that goods and people necessary for business could be easily transported over the river. The Goldie Mill, for example, had a footbridge that connected the mill on the west side of the Speed to a cooperage on the opposite side. Barrels made for packing flour could be brought from the cooperage to the mill over this little bridge. The general public often used these bridges for commuting or casual purposes. Other such bridges were present at the Taylor-Forbes plant and Presant's Mill, the latter of which was particularly popular.

Even so, a dedicated footbridge not attached to a mill would be a new thing for Guelph. This novelty may have persuaded some townsfolk that the idea was not an acceptable one.

After much wrangling, some funds (perhaps $1000) were allocated by the Board of Works towards construction of a bridge. Local surveyor T.W. Cooper was paid for plans and surveys while builder George Pike began construction of the abutments (Mercury, 15 January 1879). The bridge was on its way!

This was duly not accomplished. Funds ran short and no more were allocated for two years. For this time, only the abutments were present to bear witness to the incipient structure.

In 1881, the Council allocated $500 for completion of the bridge. When no tenders for this modest amount were received, the Board of Works called its own number and set out to construct the bridge using city workmen (Mercury, 5 July 1881). These would be overseen by George Bruce, a prominent local builder and Alderman who was also chair of the Board of Works.

("Captain Bruce, ca. 1870." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, M1991.9.2.147. Besides being a prominent builder and alderman, Bruce had been a member of the Guelph Company of the Wellington Rifles and fought in the response to the Fenian Raids.)The $500 allocation constrained the structure to a footbridge with a width of 6 feet (ca. 1.8m). Nonetheless, the piers for the bridge were built 20 feet wide (6m) so that a full road deck could be substituted when more money became available (Mercury, 16 Sep 1881). The Mercury editor thought the result incongruous and the pedestrian deck a waste of funds in light of the imminent upgrade.

After many more arguments, setbacks, and changes of mind, the Heffernan street footbridge with railings and a five-foot wide deck finally spanned the Speed river in December 1881.

Pictures of the first bridge are scarce. The only archival image that I have been able to locate is the one below:

("St. George's Church." Courtesy of the Guelph Public Library, F38-0-6-0-0-4.)If you look carefully to the left of St. George's Church, you can see the bridge extending across the Speed, with a flat deck, resting on three piers. It seems that Guelphites didn't find it very photogenic.

In any event, once opened to the public, the bridge attracted the usual sort of uses. There were complaints about the smell of refuse dumped off the approach to the bridge behind St. George's Church (Mercury, 16 May 1882). Before municipal waste collection became common, dumping of refuse at or into rivers was a common practice. Besides aesthetic issues, the resulting pile of waste gave rise to bad odours, which were thought to give rise to disease.

As ever, young men were wont to swim in the river near bridges, often in their birthday suits (Mercury, 24 June 1882). This behavior contravened the swimming by-law, which was often honoured more in the breech than the observance.

It also did not take long for a few people to ride horses over the bridge. The Mercury editor called them "stupid cranks" and warned that the practice put women and children on the bridge at risk (15 July 1882). For the townsfolk, the matter of riding horses over the bridge may have cut to the issue of just what sort of a structure it was. I suspect that many people regarded it as akin to a sidewalk: At the time, a sidewalk was a platform, usually constructed of planks, that was laid out in front of businesses or, occaionsally, as a kind of crosswalk. Horses and vehicles were not allowed on sidewalks so that pedestrians on them would not have to trouble about dodging horses or their droppings, as they would on the dirt streets of the day. Businesses might construct sidewalks and keep them clean in order to attract potential shoppers to their windows and storefront displays.

("Douglas street, ca. 1880." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 1991.35.5. Note the board sidewalks on either side of the street.)Even though it did not approach any stores, the plank deck of the footbridge was essentially a sidewalk in the eyes of many, so that riding horses on them was considered completely inappropriate.

Bridges also afford other, unintended opportunities. On one occasion, a Mrs. W.P. Howard, wife of the sexton of St. George's Church, was seen to act erratically on the bridge and then to climb over the railing, seemingly with the aim of throwing herself into the river. This she was prevented from doing by the intervention of passers-by. The Mercury editor observed (4 June 1889):

It is understood that Mrs. Howard’s mind gets a little unhinged sometimes, and yesterday she managed to elude the vigilance of her friends.Construction of the Guelph Junction Railway in 1887–88 also changed the bridge's situation. Since the rail line was built right by the south bank of the Speed, pedestrians at that end of the bridge found that they sometimes had to dodge passing trains. This was an especially daunting task at night as the space was not well illuminated.

The bridge might have weathered these hazards well enough but it suffered also from the ancient foe of Canadian footbridges: ice and floods. On 23 February 1893, for example, inspectors from the Board of Works found that the bridge had been raised up two feet on the upriver side due to an ice jam against its piers. Not good! Citizens began to complain and campaign for a replacement.

In 1896, after much discussion of materials and costs, funds were allocated and contracts let. Local builder Thomas Irving (who had worked on the Church of Our Lady) oversaw construction of the stone abutments and piers. Alderman Kennedy, chairman of the Board of Works, supplied the stone, a conflict of interest then not unusual but that did draw comment during a Council meeting (Mercury, 30 Sep 1896). The iron superstructure was manufactured and installed by the Canada Bridge and Iron Company of Montreal.

All was duly accomplished by 29 October when the work was completed and the bridge opened to the public.

Guelphites seemed to like the look of the new structure. Its solid, modern ironwork and graceful catenary curves feature in many photographs and postcards of the era.

("Foot bridge on the Speed, Guelph, Ont." Published by Warwick Bro’s & Rutter, Toronto for C. Anderson & Co., Guelph, ca. 1910. From the author's collection.) ("St. George's Church and River Speed, City of Guelph, Canada," ca. 1900. This postcard was one of "Turnbull's private postals," a very early postcards set in the Royal City. From the author's collection.) ("Footbridge, Guelph," ca. 1900. Postcard printed for the Pugh Manufacturing Co., Toronto. From the author's collection.) ("Foot bridge, Guelph, Can." ca. 1910. Postcard printed for International Stationary Co. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2004.32.61.) ("St. George's Church and Footbridge, c.1910." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.32.2760.)Despite its good looks and charm, the new footbridge did not address one of the significant disadvantages of the old one, which was proximity of the Guelph Junction Railway tracks to the south end of the bridge. Eventually, this prompted the replacement of the iron bridge with a concrete one that would look familiar to Guelphites of today. However, that is a story for another occasion.

When the old bridge was taken down in 1913, part of it was purchased by the Taylor-Forbes company. The company installed a span over the Speed just downstream from the Guelph Junction railway trestle bridge so that employees who wanted to cross the river there would not have to dodge trains (or walk around by Allan's bridge) to do so.

("Aerial Photograph, Allan's Mill, 1948." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 2014.84.569. The footbridge can be seen at the left margin, just to the right of the railway bridge, leading from Allan's mill in the foreground to the Taylor-Forbes plant across the river.)What ultimately became of that last piece of the old Heffernan street footbridge, I do not know. But, whatever the fate of its particular incarnations, the idea of the footbridge retains a firm footing in the minds and desires of Guelphites today.

Works consulted for this post include:

- Partridge, Stelter, and Seto (1990). "Slopes of the Speed." Guelph Arts Council.

21 May 2023: I have found another image of the first Heffernan street bridge! This comes from the "Diary of Fanny Colwill Calvert" (Colwill-Maddock 1981, p. 44). Unfortunately, no source is give for the image and I have not seen it elsewhere. Anyway, it looks much the same as the image given above but includes more of the bridge. I would guess that it was taken from the top of the Royal Opera building.