Although no twister struck Guelph, high winds caused extensive damage. Some of the casualities included a number of mature white pines in the University of Guelph's Arboretum. These were sometimes known as the "Zavitz pines" or "the Zavitz Pine Plantation" because the trees were the work of Edmund John Zavitz, the OAC's first professor of forestry and a pioneer of reforestation in Ontario. The plantation was part of a project to assess and promote the suitability of white pines for the purpose of reforesting the province.

Edmund Zavitz was born on 9 July 1875 on a farm near Ridgeway, Ontario. From an early age, Zavitz was much influenced by family who lamented deforestation of the land. For example, he spent some time in his early years at the farm of his maternal grandfather Edmund Prout in the Ganaraska region. His grandfather and uncle John Squair had grown concerned about the consequences of comphrensive deforestation of the region, including soil erosion, flooding, and fires. Young Edmund came to share their concerns and developed his interest in understanding what had been lost.

In early days, settlers in southern Ontario had adopted a somewhat adversarial relationship with the region's forests. In order to make their farms more productive, settlers removed woodlands as quickly as possible. This goal was accomplished sometimes by logging but also by simply setting large fires.

Although these measures produced results in the short term, they also had harmful consequences. Removal of trees encouraged soil erosion, which reduced productivity. Forest removal also had the effect of reducing the capacity of the landscape to store water, resulting in springtime floods and summer droughts. By Zavitz's day, forest cover in southern Ontario had been reduced to about 15%, with many townships reduced to about 5%. Zavitz would later estimate that about 30% forest cover would be ideal.

It occured to young Edmund that reforestation would be an appropriate and constructive response. While attending McMaster University (then in Toronto) in 1903, Zavitz read a biography of Gifford Pinchot, head of the US Division of Forestry and an instrumental figure in the professionalization of forestry. This encounter inspired Zavitz to follow in Pinchot's footsteps and become a professional forester. He transferred to Yale, whose forestry program had been founded by Pinchot, and then to graduate studies at the University of Michigan.

In 1904, Zavitz arrived in Guelph to direct establishment of a tree nursery on the grounds of the Macdonald Institute. Trees including ash, maple, white-wood, black locust, and elm were planted (OAC Review, 1904, v. 16. n. 7, p. 39). The goal of the nursery was to provide seedlings for farmers to employ for reforestation. This idea had been promoted, in part, by Charles Zavitz, a cousin of Edmund, who was a professor of crop science at the Ontairo Agricultural College (OAC). Charles Zavitz had recognized the importance of healthy woodlots to farm productivity and promoted them to farmers whom he taught and collaborated with.

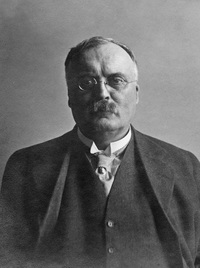

(Edmund Zavitz portrait, OAC Review, 1905, v. 18, n. 1, p. 1.)The OAC set up a Department of Forestry, in part to help direct work in its tree nurseries and to improve instruction in the subject. In 1905, upon his graduation from the University of Michigan, Edmund Zavitz joined the faculty in the new department. Zavitz immediately organized an outreach program to the province's farmers (OAC Review, 1907, v. 19, n. 9, pp. 449):

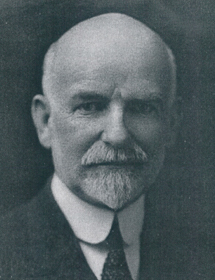

The chief problem confronting the Forestry Department is that of waste land planting. It is desired to demonstrate throughout the Province the practicability of reforesting waste land which may exist in various forms as sandy, gravelly or stony soils, steep hillsides or other untillable soil.Zavitz also mentions the establishment of a nursery for evergreens such as white pine and Norway spruce. Perhaps this refers to the white pines found in the Arboretum. (Edmund Zavitz portrait, Canadian Forestry Journal, 1913, v. 9, n. 2, p. 28.)

...

The department will furnish free the planting material, but the person receiving such shall pay cost of transportation.

The owner, on his part, must prepare the soil, plant and care for the trees, and do all the actual work in connection with the plantations in accordance with the directions of the officer of the department. The owner shall also agree to provide reasonable protection for the plantation against [live]stock or other harmful agencies.

No fruit or ornamental trees will be sent out by this department, and all trees must be used for protection or wood producing purposes.

Zavitz taught courses in forestry and related areas such as entomology. A postcard apparently featuring Zavitz is likely connected with his work as an instructor.

This real-photo card features an oval framed picture of a group of men in a forest, many carrying notebooks and binoculars, arranged somewhat carelessly for the event. Postmarks show that it was mailed from Guelph to Hamilton on 3 December 1907. The message on the back reads:Exams begin a week from Monday. Plugging is the order of the day and most of the night. How about Xmas holidays? K. B. C. // box 163 O.A.C.I'm not sure who K.B.C. was but it seems likely that he was an OAC student who is included in the portrait.

The card does not identify anyone in the picture but the figure third from the right in the back row remsembles Edmund Zavitz pretty well. Zoom and enhance! See the close-up below and judge for yourself.

As it happens, beside his academic specialties, Zavitz was a keen photographer. This was a skill he regarded as important for his work and sought to promote among his students. Shortly before this postcard was mailed, Zavitz helped to set up the the campus Camera Club (OAC Review, 1907, v. 20, n. 3, p. 159):On Monday evening, November 4th, a meeting of those interested in photography was held for the purpose of forming a Camera Club. The officers elected are as follows:—President, E.J. Zavitz; vice-president, W.R. Thompson, ’09; secretary, J.W. Jones, ’10.It could even be that the postcard photo was one of the first photos taken by members of the Club.

The organization of this Club is a much needed step in the right direction and will no doubt encourage the use of photography in the procuring of more accurate and reliable results in research and treatise work. We understand that Mr. Zavitz has kindly consented to deliver lectures upon photography to the members. Arrangements are now under way for the provision of a commodious and up-to-date dark-room, to be fitted with all the requirements of the camera enthusiast. A constitution is being drawn up and it is expected that by the commencement of the winter term, the “Camera Club” will add one more to the sum total of active and effective student organizations.

Zavitz's keenness on photography was much on display in his report on reforestation to the Ontario Parliament in 1909. Entitled "Reforestation of waste lands in Southern Ontario," the report describes the state of southern Ontario's forests, the problems stemming from it, and his recommendations for reforestation. Zavitz's photos of the sometimes severe consequences of deforestation are a compelling part of the presentation.

Figure 2 of the report shows drifting sands that resulted from deforestation in Charlottesville Township in Norfolk County. Zavitz points out that attemtps to farm in the area resulted in desert conditions due to the unsuitable nature of the soil (p. 8):

These lands originally produced splendid white pine, oak, chestnut and other valuable hardwoods. Where the land was cleared for farming purposes it gave at first, in many cases, good returns. As soon as the vegetable mould or old forest soil disappeared from the sand, it became a difficult matter to keep up the fertility and we find conditions as in the following illustrations...Figure 5 shows the stumps of a white pine forest in Walsingham Township that were not removed after logging. Subsequent soil erosion left the sizeable stumps perched in mid-air, like markers commemorating the departed topsoil. The report goes on to describe similar regions in Lambton, Simcoe, Northumberland and Durham, the latter featuring the Oak Ridges Moraine.

The report proceeds to recommend a concerted, provincial reforestation program, pointing out the benefits for soil conditions, flood control, fire suppression, recreation, and what we would today call sustainable logging.

Zavitz continued his educational and organizational work at the OAC but the scope of his amibitions for reforestation clearly could not be realized as a professor. In 1912, he left the OAC to assume the role of Provincial Forester for Ontario and Provincial Fire Inspector for the Board of Railway Commissioners. In 1926, the Provincial Department of Forests was created with Zavitz as deputy minister.

Zavitz's struggles and accomplishments are discussed at length in Bacher's "Two billion trees and counting" and are too extensive to be laid out in detail here. However, it is worth noting that Zavitz was key in the establishment of the Agreement Forest Program, which assisted municipalities in reforestation, numerous tree-control bylaws, which regulated cutting on private lands, and the creation of conservation authorities, which manage natural resources in Ontario watersheds. It is no exaggeration to say that Zavitz had a profound effect on the landscape of Ontario as we know it today.

Shortly before Zavitz's death in 1968, Premier John Robarts planted a sugar maple sapling at Queen's Park, the one billionth tree in the province's reforestation campaign (Bacher 2011, p. 218). The campaign has continued, through ups and downs. However, Zavitz's goal remains elusive. In 2010, then Environmental Commissioner of Ontario Gordon Miller (a Univerity of Guelph graduate), issued a report to the provincial legislature estimating that about a billion more trees must be planted in Ontario to reach the goal of about 30% forest cover.

In 2011, Edmund Zavitz's grandson Peter gathered with University of Guelph president Alastair Summerlee, Prof. Andy Gordon, School of Environmental Sciences, and Robert Gordon, dean of OAC, to unveil a plaque dedicated to Zavitz and his work. The plaque is situated in the northeastern corner of the Arboretum, where some of Zavitz's white pines stand to this day.

Below is one of the surviving Zavitz white pines standing near the plaque.For more information, see:

- Bacher, J. (2011). "Two billion trees and counting: The legacy of Edmund Zavitz," Toronto: Dundurn Press.