The writer for the Mercury was very pleased with what he heard:

The singing was in every respect first-class, and the pieces sang were of a sacred character, mostly plantation songs, the composition of which went to show that although the black man was a slave and in the house of bondage, the spirit was unfettered, and that he was a freeman in the highest sense of the word. Whether in the low and plaintive wail of sorrow, or in the high and jubilant song of victory, there was alike displayed a pathos and vigor enchanting. While the clear intonation in which the words were uttered made it capable for everyone to catch the words distinctly, and while enjoying the music of the song were able to appreciate the words.As the review suggests, the source material of Spirituals was songs sung by enslaved persons in the antebellum American South. Following the US Civil War, performance of this folk music had become the foundation of an entertainment industry that put black musical culture on the same stage as its European counterparts.

The review goes on to name some of the songs performed and the performers themselves:

In such songs as “Hard Trials,” “Ring dem bells, Peter,” etc., which were rendered very powerfully—the singers were loudly encored. Mr. J. O’Banyoun conducted the music, and was well supported by Mrs. O’Banyoun, who also presided at the organ, assisted by Master Ernest O’Banyoun, Mrs. Bland, Messrs. A. Johnston and J. Holland.The Rev. Josephus O'Banyoun was born in Brantford, Upper Canada, in 1838. His father, Simon Peter O'Banyoun, had escaped slavery in Kentucky and sought freedom in Canada. He was pastor of an American Methodist Episcopal church in Brantford, which later joined with the British Methodist Episcopal (BME) church following its foundation in 1856. ("Rev. Josephus O'Banyoun," from Wright, R.R. and Hawkins J.R. Centennial encyclopaedia of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, 1916, p. 377.)

The apple did not fall far from the tree: Josephus became a minister in the BME church. He gained a reputation for his skill as a singer and became one of the most accomplished concert company managers in the country, leading the Canadian Jubilee Singers, in its various incarnations, on tours of North America and Western Europe.

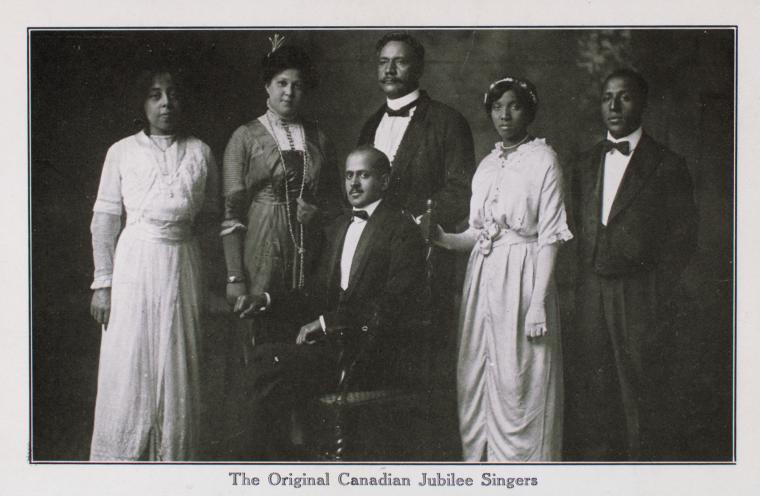

("Famous Canadian Jubilee Singers," 1902; courtesy of Library Archives Canada R5500-363-9-E.)On this occasion, the Jubilee Singers had embarked on tour for a particular purpose: To help raise money to reconstruct their church in Hamilton, which had been destroyed by fire. This mission reflected the origin of the Jubilee singing phenomenon, which was to raise money to support a black cultural institution.

Following the US Civil War, various liberal and activist groups sought to enhance educational opportunties for formerly enslaved people in the US South. One such initiative was Fisk Univerity, in Nashville, Tennessee, founded in 1865 by the American Missionary Association and named in honour of Clinton Fisk, a Union general who secured a site and funds for its inception.

Housed in decrepit former army barracks and in constant need of more cash, a group of its students went on a fundraising tour of northern states in 1871. The group had trained for several years and toured locally with some success but it was felt that performances for more liberal—and well-to-do—audiences in the North would be more productive.

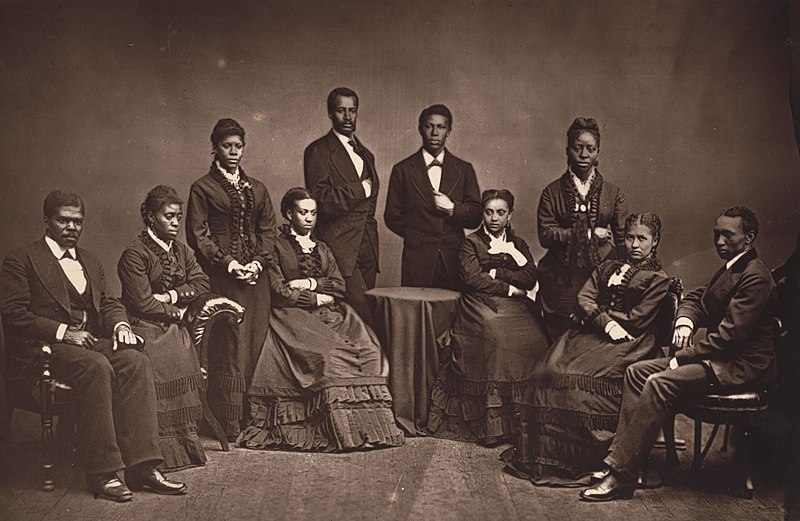

("Fisk Jubilee Singers, 1875," courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)The tour was a do-or-die gamble: Arranging the tour took all the resources that Fisk University had left, so that failure of the tour could well mean closure of the school. At first, response to the group was tepid among white audiences: While their performances were techically superior, their repertoire was conventional popular music and failed to resonate. However, it was noticed that audiences responded well to pieces derived from so-called plantation songs. Performances were rearranged to feature these pieces and the group was christened "The Jubilee Singers" in November, a reference to the Jewish year of jubilee or emancipation, not to mention its general association with celebration of significant events. The troupe considered this name dignified and it struck a chord with the public as well.

("Steal away to Jesus," often first in programs of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Courtesy of the Barbershop Harmony Society.)The Jubilee singing phenomenon was born! By the end of 1872, the Fisk Jubilee Singers had featured at the World Peace Festival in Boston and sung for President Grant at the White House. Signature numbers such as "Roll Jordan, roll," "Steal away to Jesus," "Swing low, sweet chariot" became known to all. The tour raised $20,000 for a new building. In 1873, the troupe began a European tour.

("Roll, Jordan roll," from Twelve years a slave, 2013.)Given this kind of success, it is no surprise that many Jubilee singers followed in the wake of the Fisk troupe. Many groups, such as the O'Banyoun Jubilee Singers, followed the Fisk model and sang spirituals arranged for performance in concerts to passive audiences. Others incorporated spirituals into other forms of entertainment. For example, they soon found their way into performances of Uncle Tom's Cabin, set on plantations in the antebellum south. In these shows, spirituals were presented in a traditional mode where everyone present (on stage) sang together, more like hymns sung in church by the congregation rather than by the choir only. Of course, spirituals were also incorporated into variety acts and minstrel shows, where parodies or comic pieces, such as "Oh, dem golden slippers," were performed.

Jubilee singers did not take long to get to Guelph. The ad below appears in the Mercury (13 Feb. 1878):

The ad certainly provides clues as to some of the attractions that jubilee concerts had for white audiences. Its emphasis on "genuine colored people" reflects the significance of authenticity to audiences. Accustomed to minstrel shows in which black people were portrayed and mocked by white people in blackface, the ad assures readers that the proposition in a Jubilee concert involved no imposture—it was the real deal.As Graham (2018, pp. 249–250) comments, formal Jubilee concerts offerred white audiences an apparently direct connection with black performers:

Student jubilee concerts served as a forum in which whites with no previous experience of plantation slavery could imagine that they suddenly understood the pain of the freedmen.The music was certainly touching and many audience members were moved to sympathy. Still, the effect itself was something of an illusion:

The singers were seen as a symbol rather than as individuals, and their spirituals represented an imaginery Other that encompassed essentialized notions of blackness, slavery, and ultimately Africa.Of course, the singers did not see their performances in the same way. The Fisk singers had initially been reluctant to sing spirituals in public precisely because of their association with slavery. However, they came to see the music not as a throwback to that era but as a public assertion of their musical culture on terms at least signficantly under their own control. Their mission was to promote the education and advancement of black people by presenting themselves to the general public as performers with talents, skills, and material that were to be taken seriously. In this mission they certainly succeeded: Troupes like the Fisk and O'Banyoun singers raised significant amounts of money and support for their causes. ("Swing low, sweet chariot," Fisk University Jubilee Quartette, Victor Records, 1909.)

In addition, the Jubilee singing phenomenon became, as Graham puts it, the birth of a black entertainment industry. Despite its shortcomings, the demand for authenticity that it brought created a space where black performers could represent and promote themselves. The scope of demand also created career opportunities for black muscians, albeit in a system dominated by white businesses. Even after interest in Jubilee singing faded, its precedent made room for the growth of further black musical genres such as blues and jazz.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, re-formed after their European tour, visited Guelph in 1880, 1881, 1882, 1883, 1888, 1889 and 1892 (on the last two occasions as the Tennessian Jubilee Singers). These performances were sell-outs and were praised rapturously in the Mercury (e.g., 26 Oct. 1881):

Nothing in the way of music could be sweeter or more harmonious than the blending of voices, now sinking to softness like the sound of distant chimes, then swelling into rich volume like the tintinnabulation of silver sounding bells wafted on the breeze.The length of the concert was doubled by demands for encores, "and the audience dispersed delighted with the entertainment."

Other American troupes that performed in town included the Sheppard Jubilee Singers mentioned earlier, the Memphis Jubilee Singers, The Nashville Students, and the Ball Family Jubilee Singers.

The O'Banyoun Jubilee Singers performed in Guelph numerous times. Sometimes, these visits were meant to raise funds for their own purposes. On other occasions, they were in support of the local churches. For example, they gave a concert at the City Hall on 18 Sep. 1880 as part of the celebration of laying the cornerstone of the BME church on Essex street. When the church was officially opened the next year, the Singers performed a number of songs and the Rev. O'Banyoun presided over the ceremony.

A related troupe was the Canadian Jubilee Singers, organized by William and Sadie Carter, which included a number of Hamiltonians such as Mrs. Bland-O'Banyoun, Josephus O'Banyoun's fourth wife, and his son Earnest. Formed in 1878, the group was an international hit, touring Europe and the United States for a number of years.

(Postcard of "The Original Canadian Jubilee Singers," courtesy of the New York Public Library NYPG00-F335.)This group performed in Guelph several times, such as on 19 June 1889, as indicated in the Mercury ad below.

A cakewalk was a dance in which black performers would perambulate about a square in an elaborate choreography that served to show off their agility and also mocked the stereotypical mannerisms of well-to-do white people. The couple that gave the best performance took the prize, which was an elaborate cake—thus the English expressions "to take the cake" and the ironic "easy as a cakewalk."

By the late 1880s, interest in Jubilee concerts had begun to wane due to familiarity and growing interest in other music genres. The presence of a cakewalk in the 1889 Guelph concert is evidence of this trend. After the US Civil War, cakewalks featured in minstrel shows but became a popular activity in many kinds of get-togethers. The music played during cakewalks became a predecessor of ragtime, so its presence in a Jubilee concert suggests that performance of spiritual songs was no longer sufficient to meet audiences's expectations.

Besides touring companies, Jubilee singing was also performed by local companies, and Guelph was no exception. Members of the congregation of the BME church on Essex street performed them for local audiences. It is not clear when this effort began, but the Mercury (26 June 1891) mentions that members of the BME choir assisted in the performance of a concert featuring members of O'Banyoun's company during an event the Norfolk street Methodist church.

An early mention of Guelph's own Jubilee singers appears the following year (21 March 1892):

W.C.T.U. Concert.—The third of the series of Saturday night concerts under the auspices of the W.C.T.U. was held in the R.T. of T. hall. The attendance was large. The chair was occupied by P.C. Kenning, of Guelph Council. After the opening hymn and prayer, Rev. Mr. Cunningham delivered a short address on the evils of intemperance. The Guelph jubilee singers, eight in number, then gave a programme of jubilee songs and hymns, which was interspersed with readings by Miss Maddock and Mr. Payne. The jubilee singers were the chief attraction, and several of their selections were encored. A vote of thanks moved by Mrs. Jones, President of the W.C.T.U., and seconded by Mr. Payne, was tendered to the jubilee singers, and the singing of God Save the Queen brought a very pleasant evening’s programme to a close.It seems clear that Jubilee singing was well established at the Guelph BME church by this time. This impression is confirmed by the fact that Miss Melissa Smith, a young member of the local congregation, toured with the Canadian Jubilee Singers for about six months at around this time.

Mentions in the Mercury of local Jubilee Singers connected with the BME church continue through the 1890s, where they are described as the "BME Jubilee Singers," the "Guelph Jubilee Singers," the "Royal City Jubilee Singers," and the "Evening Bell Jubilee Singers." There is even mention of Junior and Senior Jubilee groups, suggesting that the church had a deep bench of talent in the field.

The most fulsome description of a concert by the local group is connected with a church performance (Mercury, 21 Oct. 1896):

The concert given in the B.M.E. church on Tuesday evening by the Evening Bell Jubilee Singers was a success not only in the extensive programme, but also in attendance. The little church was well filled with people of all denominations and the programme was first-class in every respect. The jubilee songs and hymns by the company were excellently rendered, and the quartettes by Mrs. Waldron, Messrs. A. Waldron, J. Waldron, Miss Cromwell and Mr. A. Waldron were exceptionally well sung. Mr. A. Waldron’s solos were cleverly given. The Misses Williams also sang some pleasing duets. Their singing was the feature of the evening. They were accompanied on the organ by Miss Schofield. Another new candidate for public honors was Mr. J.H. Matthews who, in his solos and guitar accompaniments, stamped himself as a clever performer. The violin solos by Mr. Joseph Mallott were fairly well performed. The chair was occupied by Mr. E.J. Tovell, who, in his opening remarks, bade all a hearty welcome. It is the intention of the singers to give a concert once a month, the proceeds of which will go to pay the indebtedness of the church. The company give a concert in Freelton next week.It's not clear yet how long Jubilee singing persisted as a genre at the BME church, although jubilee songs were on the program for the installation of a new organ in 1922 (Mercury, 14 Feb.).

In any event, it is clear that Jubilee singing was an important part of the musical scene in Guelph, as it was elsewhere, and that it played a significant role in the local black community as well.

Works consulted include:

- Abbott, Lynn, and Doug Seroff. Out of sight: The rise of African American popular music, 1889-1895. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2009.

- Brooks, Tim. "Might take one disc of this trash as a novelty": Early recordings by the Fisk Jubilee Singers and the popularization of" Negro folk music." American Music (2000): 278-316.

- Files, Angela. The O'Banyoun Jubilee Singers of the early British Methodist Church in Brant. Brant Historical Society, 1995.

- Graham, Sandra Jean. Spirituals and the Birth of a Black Entertainment Industry. University of Illinois Press, 2018.

- Graham, Sandra Jean. Biographical Dictionary of Jubilee Concert Troupes.

- Henry, Natasha. Change starts now: Our stories, our history, our heritage. Guelph Black Heritage Society, 2022.

- Shadd, Adrienne. The journey from tollgate to parkway: African Canadians in Hamilton. Dundurn, 2010.

("Swing Low, Sweet Chariot: 150 Years of the Fisk Jubilee Singers," courtesy of American Experience—PBS.)

(Michigan J. Frog performs a cakewalk dance to the ragtime tune of "Hello! Ma baby," in the Warner Bros. Looney Tunes cartoon "One froggy evening," 1950; courtesy of WB Kids.)