It is the intention of James L. Simpson, the owner [of Simpson's Mill], to lay out a complete private park, with all the usual facilities of such playgrounds, including swimming pools, camps sites, dance hall, dining room, tourist accommodation and other similar facilities.With Guelph in the depths of the Great Depression, the arrival of a new amusement facility must have been welcome news to many.

The news also concluded the efforts of James Livingstone Simpson to sell his property to the City of Guelph, which proved, perhaps also due to the Depression, not to be receptive to the idea of buying the land to add to Riverside Park. Rebuffed by the city, Simpson decided to set up in the recreation business for himself.

Simpson's Mill sat on property along the Speed River, on the north side of Speedvale Avenue just east of the bridge then often known as Simpson's bridge. Today, the property houses the Speedvale Fire Station and the John Galt Garden. However, the site had a long history as a mill.

In 1859, Mr. John Goldie bought 17 acres of land along the east bank of the Speed from William Hood as an inducement for his son James to immigrate to Canada from New York and become a miller. The property was already the site of a sawmill and barrel-stave factory operated by Samuel Smith, a former Reeve and Mayor of Guelph. A dam constructed across the Speed about 200 yards south of what is now Woodlawn Road fed water into a raceway that led to the sawmill and factory, situated near the east bank about where the current footbridge is located.

(James Goldie (1824–1912); photo courtesy of William Weston.)James Goldie took the bait and brought his family to the new site, which was accessible only by a footpath from the Elora Road (now Woolwich Street). The family lived in Smith's old stave factory while they built a new mill complex. They built a new dam next to the sawmill (where the current dam stands) and constructed a large raceway down to their new flour mill further south near Speedvale Avenue.

The new mill consisted of two sections. The first section was the mill proper, built of local stone, and housed the water wheels, grinding stones, and other equipment for a flour mill. The second section was a frame building made for storing grain. By the end of 1861, the new mill was in operation and the old sawmill repurposed as a stable.

The site also incorporated a cooperage, as flour was usually shipped in barrels rather than bags, and several coopers employed.

James Goldie bought the People's Mill (now known as Goldie Mill) in 1867 and sold the old place to Mr. John Pipe, a local farmer. It was therefore known as Pipe's Mill until 1883, when Pipe sold it to G.P. Tolton. Mr. Tolton installed a new-fangled roller system from the US known as "The Jumbo" (doubtless after the famous elephant), which locals honoured by dubbing the mill "The Jumbo Mills."

(Speedvale Mill, ca. 1870. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 2014.84.1025.)With water levels falling in the Speed, the mill's water wheels had difficulty supplying Jumbo with enough energy to work properly. Mr. Tolton introduced a steam engine, which supplied the necessary power. Like its namesake, Jumbo had bad luck with steam engines and was disposed of in favour of steel rollers. Perhaps with some disappointment, the mill returned to being "The Speedvale Mill."

After passing through other hands, the mill was sold to James Simpson in 1901, thus becoming "Simpson's Mill." Finding that flour could no longer be produced profitably, Mr. Simpson converted the mill to grinding animal feed. This he did until his retirement in 1926, at which time he moved to a house on Wellington Place (now Riverview Drive) leased the mill to Joseph Lang, who continued the operation.

Besides the mill, the grounds also became an attraction connected with Riverside Park. The Park had been opened in 1905 as a place for Guelphites and others to find wholesome, outdoor entertainments and to get people onto the city's streetcar system.

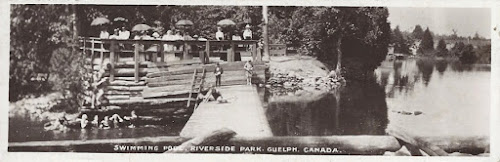

One of the attractions was the opportunity to swim (or "bathe") in the Speed River at the dam belonging to Simpson's Mill. In fact, Mr. Simpson obligingly erected a new dam made of stone and concrete, which rose a couple of feet higher than the old one, in order to create a deeper reservoir that would make for better boating and bathing opportunities for park patrons (Mercury, 25 May 1905).

(Swimming in Riverside Park, from a postcard by Charles L. Nelles, ca. 1905.)As a part of his mill operation, Mr. Simpson's property included the "water privilege" for the section of the Speed river adjacent to his mill. In short, he had the right to use the water to power his mill and to exclude others from using the water there. As a result, the city paid Mr. Simpson a monthly lease so that Guelphites could splash and swim in the water at Riverside Park. At first, the lease was $50/year, although it was later increased to $100 (Mercury, 2 June 1932).

All went well until fire, that ancient foe of millworks, struck at Simpson's Mill. On 17 July 1930, city firemen responded to a report of flames at the mill (Mercury, 16 April 1947):

A full turnout responded, and a long line of hose was laid from Elora Road, then split to two lines near the mill. Horses were taken from the stables and led to safety, while water was poured into the blazing building. Firemen fought the blaze for three hours before it was brought under control.The cause was deemed to be spontaneous combustion of hay in the loft.

It turned out that this blaze was only a prelude. A year later, another fire caused a conflagration that finished what the first fire had begun. Despite all efforts to save the structure, nothing but smoking walls were left of Simpson's Mill in its aftermath.

Apparently, 70 years of milling on the site was enough. Rather than rebuild, Mr. Simpson tried to interest the city in purchasing the property, for provision of a recreational facility added to Riverside Park. This offer sparked serious interest, as at least a few citizens thought that Guelph should have a bona fide public swimming pool. Yet, the culture of the "swimmin' hole" remained strong, as evidenced by this letter to the editor of the Mercury pointing out that citizens of the Royal City yet enjoyed many swimming locales, many outdoors (4 July 1931):

Dear Sir:—I noticed in Thursday night’s Mercury somewhat of a cyclone of agitation for a municipal bathing and swimming pool in Guelph, and, Mr. Editor, I confess that I fail to see the great urgency claimed by the agitators. We have the large pool in Riverside Park, which is well patronized, the Y.M.C.A. swimming pool, which is also an important adjunct, and if we walk for a quarter of a mile from the eastern end of the York Road street car line, we can get any quantity of accommodation in the swimming pools on the Reformatory grounds, which are free to city bathers. Furthermore, the Kiwanis Club have a site for bathing between Norwich Street Bridge and Goldie’s Dam, which is unsurpassed for a bathing pool for children. ...In the end, the city declined. Simpson then demanded an increase in the water rights lease to $150/year. After further controversy, this too was declined.

To the mind of this writer and many others, the city of Guelph is wondrously well equipped with bathing pools and “swimmin’ ‘holes,” and ... could have right near the heart of the city abundant accommodation for all classes of bathers and swimmers.

In 1932, Mr. Simpson took matters into his own hands. He decided to turn Simpson's Mill into a recreation centre on his own account. He began by erecting a fence between Riverside Park and the Speed River (Mercury, 2 June 1932). The fence ran the length of the Park, cutting off the river walk, the dam, the bathing huts, and the pavilion from the riverbank. Park patrons would no longer have any access to the water. As the Mercury writer put it:

There will be no river at Riverside Park this year.... Visitors to Riverside Park who wish to see the water this year will be compelled to do so while looking through a fence.Alternatively, Guelphites could make their way to the new recreational facility that Mr. Simpson was building on the old mill site. The main attraction of the new facility was to be a pair of swimming pools, one for adults and one for children. Both pools would be fed by the mill race with a constant stream of river water.

At the south end of the race, the adult pool would be the most ambitious installation:

It will be 430 feet in length and 90 feet wide with a sand bottom, six inches in depth. The depth of the water will be nine feet at the peak, but is will be possible to drop it as low as two feet. It will be built in the form of a bowl, with a shore line around it.Immediately upstream and separated by a floodgate would be the children's pool:

This pool for the youngsters will be 100 feet long and 26 feet wide and will be paved with brick, while the water level will be kept at a safe height.The whole scene would be illuminated by lights attached to a 40-foot tower, allowing for nighttime use.

Besides the swimming pools, walking paths and picnic sites would be provided. In addition, part of the old mill structure would be renovated and converted into a dance hall with a dining hall upstairs.

(Car park at Old Mill Swimming Pool, ca. 1935. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 1985.59.2.)Mr. Simpson's concept turned out to be a popular one and the "Old Mill," as it came to be called, was well patronized for many years. For example, the city swimming championships were held there in 1933 (Globe, 8 August 1933). Thirteen-year-old Kathleen Sinclair won the girls' title while "Peewee" Brandon won the mens'.

(Children swimming at Simpson's Mill, ca. 1935. Courtesy of Guelph Public Library archive item F38-0-15-0-0-418.) (Old Mill Swimming Pool, ca. 1935. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 1985.59.3.)Entitled "The Old Mill Swimming Pool" in local phone books, the facility continued operations for many years. Dickering with the city over water rights continued also, apparently without bearing fruit. In 1940, the city's Public Works committee recommended that the city purchase the property for a sum of about $3000 (Mercury, 7 May 1940). In the view of many aldermen (councilors), the need for the city to have a decent swimming pool was pressing and the property was well-suited for construction of one.

Ald. Wilson stated that ... “We are all agreed this is the right time. For a city of this size, we are all agreed we need a swimming pool. If we buy this, in the near future we will have a swimming pool second to none."Although only one alderman opposed the measure, the purchase did not go through. (Six people swimming at Simpson's Mill, ca. 1930. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 1978.38.7.) (Detail of booklet, "Why we chose Guelph" (1945, p. 19). Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 1985.82.119.) ("Speed River near Old Mill," postcard published by Photogelatine Engraving Co., Limited, Ottawa, ca. 1950.)

In 1944, Mr. Simpson died and the Old Mill became the property of Wilbert Nisbet, who had been operating it for Mr. Simpson for some years. After Mr. Nisbet's death in 1956, the city finally completed purchase of the property. It appears that the Old Mill was no longer as popular as it was and that the city did not continue to operate the pool or dance hall. In addition, construction of the Memorial Pool in Lyon Park in 1952 had satisified the city's need for a public swimming pool. Instead, the city began to make plans for a general renovation of Riverside Park and its new addition.

(Pavilion and old house at Simpson's old mill, flooded by Hurricane Hazel 1954. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 2014.84.1019.)Even so, the Old Mill had a second act. It was rented out to the Guelph Little Theatre in 1960 (Globe, 10 September 1960). In January, 1959, the group had rented the dining hall for a party, trying to keep its membership engaged between productions. The hall was decked out to look like a Klondike saloon, apparently to suit the drafty nature of the old building. The party was a hit and the company, on the lookout for a new theatre, convinced the city to rent it to them on an ongoing basis. It was duly painted and repaired for the purpose.

(Guelph Little Theatre building (Old Mill), ca. 1960. Courtesy of Wellington County Museum and Archives A1985.110.)However, the reprieve was only temporary and, after the city had decided on its plans for the new property, it lowered the curtain on the Old Mill in 1963. In its place were established the John Galt Gardens, commemorating the foundation of Guelph, and the Fire Hall, on the site of the old mill that had been destroyed in two blazes 33 years before.

Sources consulted for this post include:

- The Guelph Evening Mercury (20 July 1927/Centennial edition, § 7), "Speedvale Mill."

- McIntosh, A.W. (1965), "Speedvale mill: A mill in Wellington County."

It is curious that the only postcard to mention the Old Mill is the one above, which provides an image of the old suspension bridge over the Speed River at Riverside Park. Given that the Old Mill was a popular attraction, postcards that show it, and not simply a locale "near" it, would be expected.

On a related note, another run of the same postcard shows the scene a little differently. See if you can spot the difference:

I think that the first view above is correct but I am not a hundred percent sure.In any event, the history of the Old Mill should be better known. If you have any further information about it, please let us know in the comments below. Thanks!