In the chilly afternoon of 8 November 1920, a group of people crossed over the Eramosa River on the sturdy, concrete bridge to the Canadian Pacific platform at the Speedwell station. They were the last patients and staff of the Speedwell Military Convalescent Hospital, commonly known as the Speedwell Hospital. They consisted of 45 walking patients, 9 "stretcher cases," 2 doctors, 7 nursing sisters, 3 vocational aides, and 9 orderlies. They boarded the 3:40pm train for Toronto, bound for Christie Street Hospital. The Speedwell Hospital was now closed.

(View of the Prison Farm from near the Speedwell train stop. Printed by International Stationary Co., Picton. Although the card is from ca. 1912, the note on the back says, "This is present Speedwell Hospital.")

The story of Speedwell Hospital begins in 1915. It had become clear that the conflict in Europe was going to be a long and grinding affair. Many personnel sent off to war were coming home badly wounded and in need of substantial care, and many more would do so in future. In June of that year, the Canadian government set up the Military Hospitals Commission (MHC) to acquire and operate a system of hospitals and other facilities to see to the needs of returning veterans. Given the pressing nature of the situation, the MHC was on the look-out for existing facilities that it could adapt for its purposes. The Ontario Reformatory at Guelph, still often known as the Prison Farm, was a good candidate. It could certainly serve the medical needs of wounded veterans but, more to the point, its farm and machine operations could provide employment and vocational training for veterans as they re-integrated into civilian life.

The choice of the Prison Farm was telling in some ways. The Prison Farm had been designed to turn young men from lives of petty crime or dissolution to lives as productive and upright citizens, learned through agricultural work or tradecraft. Although the Speedwell Hospital was to function as a medical facility, it too had a broader social function. Like the Prison Farm, it was intended to turn young men from soldiers into civilians through experience with agricultural work or useful trades.

Soldiering was generally viewed as heroic and not criminal, yet the fundamentally undemocratic operation of the military and the dependency of its rank and file on the organization were regarded as problematic for civilian life. Thus, Speedwell would be a place where returned soldiers would be honoured and healed but also helped to begin lives as the heads and breadwinners of the nation's future families.

Unfortunately, Speedwell did not succeed in this mission.

On 19 October 1917, the first 50 returned soldiers were brought to Speedwell from the London Military Hospital (Evening Mercury). The Prison Farm had been thoroughly renovated in preparation for their arrival. Of course, bars and screens had been removed from windows and iron doors replaced with curtains. Painters, carpenters, and other tradesmen from Guelph had been busy for months making the place more welcoming and less confining.

(Military Hospital, with a new dormitory wing visible on the right. Printed by the Heliotype Co. of Ottawa, ca. 1920.)

In addition, two new wings had been built as dormitories. Each was two storeys high and could accommodate 74 beds on each floor, for a total of 296. In addition, a large theatre had been constructed behind the Main Building, with a capacity of about 600. Here, soldiers could put on entertainments for each other, for visitors, or be entertained by special guests. A recreation room featuring billiard and pool tables as well as pianos was provided. A library was also fitted up, and a call for book donations put out. A canteen was constructed in the basement where patients could eat cafeteria style, if they could.

(Soldiers playing billiards at Speedwell. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums

1978.6.4.)

(Soldiers at a Speedwell cafeteria. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums

1978.6.1.)

Vocational training was also organized. Patients could get training in the trades, such as carpentry and auto mechanics. Remedial schooling was also available.

(Soldiers making furniture in a carpentry shop at Speedwell. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums

1978.6.5.)

As part of the deal between the Department of Soldiers' Civil Re-establishment (DSCR—successor to the MHC), command of the hospital remained with the military, headed by Lieutenant Colonel T.G. Delamere, a veteran of the first Canadian contingent to France who was wounded in action and returned to Canada. Even so, many of the staff of the facility would continue to be civilians, many remaining from the Prison Farm days.

(Real photo postcard of Speedwell, taken from the north with a Farm side road in the foreground.)

In some respects, Speedwell Hospital served its patients reasonably well. Opportunities for playing billiards, reading books, and writing letters and postcards were likely agreeable. Many special entertainments were mounted also. For example, sporting events were brought in. On 14 April 1919, for example, a boxing program was put on featuring "Irish" Kennedy versus "Battling" Ray of Syracuse (Globe). Although scheduled for 10 rounds, Kennedy knocked out Ray with two telling blows to the jaw in round 5. A wrestling match between Finnemore of Milton and Hays of Galt went nearly 25 mintues, when Hays made the second fall of the bout. The Eustis Bros. of Toronto delighted the assembled with their excellent acrobatic display. Three boxing matches between returned soldiers were well fought and ended in draws.

In 1919, amateur baseball returned to Guelph, and the Speedwell Hospital entered a team. The experience seems to have been a success as Speedwell went on to enter a team in 1920 as well.

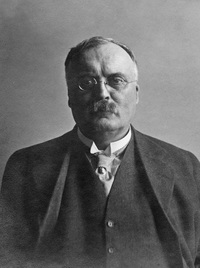

Edward Johnson, local boy who was already an international singing sensation, put on a show to a packed audience at the Speedwell theatre on 10 September 1920 (London Free Press, 11 Sep.).

(Edward Johnson as Pelléas in Claude Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1925. Courtesy of

Wikimedia Commons.)

Soldiers at the the Hospital also organized their own entertainments, which were sometimes made available for the community. For example, the Speedwell Hospital Minstrels put on a minstrel show in the old Guelph City Hall (Evening Mercury, 19 Feb. 1920). Minstrel shows were variety shows in which white men wore blackface and capered, sang, and played instruments in the manner they imagined southern African Americans did. The form had been largely superseded by Vaudville style shows but persisted as an informal kind of amusement. The Speedwell Minstrels' performance was liked well enough that they were invited to repeat it in Elora.

Ties between the returned soldiers and the community seem to have been positive. Reports suggest that many soldiers remained in Guelph after their time at Speedwell, though I have not found accounts of exactly who they were or how numerous. Connections with town were facilitated by the Toronto Suburban Railway stop at Speedwell station, across the Eramosa River from the institution. The Guelph Radial Railway (streetcar) opened a regular service to Speedwell (Evening Mercury, 15 Jan. 1920). Business on this route was so good that two extra daily trips were put on, which were filled to capacity.

(Storage building at Speedwell; Construction v. 13., n. 3, p. 97, March 1920.)

Various aid organizations, many run by women, took a great interest in the well-being of the soldiers, for example (Globe, 19 Dec. 1919):

The Speedwell Hospital Visiting Committee of the Red Cross Society at Guelph yesterday prepared the personal property bags and packages which are to be distributed to all the patients of the hospital. The committee received many generous donations for these packages, which will contain raisins, chocolates, smokes, socks, handkerchiefs, apples, and other articles. In each there is also a Christmas card and a Red Cross card. The distribution of gifts will be made on Thursday afternoon.

Soldier's Comfort Committees in many communities made goods and campaigned for funds to provide soldiers with domestic comforts. For example, the Women's Institute of Ospringe made and donated

an "autograph quilt" to the Speedwell Hospital in 1919.

At the provincial level, Mrs. Arthur VanKoughnet of the DSCR coordinated a funding drive with impressive results (Globe, 7 Oct. 1919):

Oakville Woman’s Patriotic League, $200.00; Seaforth Canadian Red Cross Society, $125.00; St. Cyprian’s Carry on Club, $130.50; Riverdale Woman’s Patriotic League, $225.00; Woman’s Volunteer Corps. $125.00; Grey County Woman’s Institute, Ayton, $202.00; Ioco Good Cheer Club, $66.00; Gorrie Woman’s Institute, $54.50; Annan Woman’s Institute, $30.00, and others from individuals. Donations of comforts of various kinds were received from Sherbourne Street Methodist Church, Jarvis Street Patriotic Society, Navy League of the United States, York Rangers’ Chapter I.O.D.E., Sir Thos. Cheton Chapter, I.O.D.E., Hastings; W.I. Roseneath, Cobourg Ladies, 169th Regt., St. Alban’s Red Cross Society, North Toronto Red Cross Society and Soldiers’ Comforts, D.S.C.R., 71 King street west.

Some of the soldiers applied themselves to the domestic arts, perhaps those who were unable to work in the abbatoir or carpentry workshop. Some of the fruits of their labour, from Speedwell and other facilities, were put on display in the Women's Building of the Toronto Exhibition (Globe, 26 Aug. 1919):

There are beautiful scarves and hat bands woven on hand looms, beaded necklets and watch fobs of fine color and design; examples of metal work, hammered brass and copper; cushion covers and centerpieces in embroidery and cross stitch; excellent carpentry and cabinet work; beautifully carved and inlaid trays; hand-painted China and other things almost beyond his number.

Above all, the author heaped praise on the fine baskets that the men had made.

The author also took pains to maintain the dignity of the soldiers. Although this work was of a traditionally feminine character, it "may frequently set an example of the beauty of usefulness and simplicity to the women who exhibit their achievements in the adjoining rooms." In other words, the soldiers' scarves, embroidery, and baskets were safely masculine, and admirably so.

Of course, some items were decidedly military, such as a belt made of war trophies, a kind of art practiced in the trenches in France:

A unique contribution to the collection is a belt made from captured German regimental badges, and clasped with the regulation German brass buckle bearing a crown and the words “Gott Mit Uns.”

In spite of these efforts and the benefits they conferred, returned soldiers experienced significant troubles at Speedwell.

Some troubles were consequences of the war. For example, George William Moyser of the 71st Battery of Toronto, died as a result of ill-health caused by a gas attack suffered in France (Globe, 28 May 1919). Others were due to misadventure. Fred Tucker died as a result of falling off the top of the quarry pit at the back of the Hospital (Daily Star, 11 Aug. 1919).

Many soldiers were killed as a result of the Spanish Flu epidemic. For example, Lavelle Germain of St. Marys was taking a vocational course at Speedwell but staying in Guelph. He returned to his room at the King Edward Hotel complaining that he felt unwell. He later called for a doctor, who arrived to find Germain all but dead (Evening Mercury, 3 Feb. 1920). A whole ward of Speedwell was converted into a ward for flu victims, and several ill students from the O.A.C. were moved in (London Advertiser, 10 Feb. 1920).

Of course, the Spanish flu affected everyone. Nursing Sister Miss Geraldine McGinnis of London died of pneumonia resulting from the flu (London Advertiser, 12 Feb. 1920). She must have been very dedicated to her vocation as she had served two tours in France during the war and was in her second stint as a nurse at Speedwell.

Physically, Speedwell itself was not well suited to work as a hospital. Among the many problems was the damp. The stone walls of the institution seemed to encourage condensation, making the rooms continually uncomfortable. Dampness was a particular problem for the "lungers," that is, the many tuberculosis patients housed at Speedwell. Patients complained bitterly to a Mercury reporter who went to investigate (Evening Mercury, 8 July 1920):

Vincent is a British naval veteran, in with bronchitis. “The floors here are like the decks of a battle ship,” he said. “I had some experiences in the navy, was mined twice, but the experience I have had here are worse than the former ones.”

...

“It has to be a pretty wet place before I’ll complain of it,” said “Pick” McRae, “but you can tell ‘em all it’s too wet here for me.” McRae is a lung patient in cell number 9. Water was dripping from the walls of his cell.

As the word "cell" suggests, Speedwell retained the look and feel of a prison, in spite of the renovations and amenities. Naturally, the patients found this quality disheartening.

Speedwell had significant institutional problems as well. The DSCR's contract with the Ontario government meant that civilians staffed many of the Hospital's operations, such as the farm. Veterans felt that they should have preference for work at Speedwell and resented limitations on their opportunities there.

Budget limitations also led to conflicts among the staff. Nurses at Speedwell, who belonged to the military organization, complained that their medical duties did not allow them time to deliver and supervise patients' meals, as expected by the institution's dietitians, who belonged to the civilian authority. The dietitians complained that there was not enough money available to hire civilian staff to carry out that duty.

("Portion of the spotlessly clean kitchen at Speedwell, wherein cooking is a ?? and diet a study. No dish is used whereon one germ exists and frequent tests keep up this desirable condition." The London Advertiser, 20 Dec. 1919.)

In 1920, the situation came to a head. One hundred and fifty patients signed a petition demanding a sharp improvement in hospital conditions. They and the Great War Veterans Association (GWVA) called for the resignation of the Hospital administrators and for jobs at Speedwell to be given to veterans before civilians. Many of the nurses walked off the job in protest at conditions in the Hospital. A provincial inquiry found that want of money had led to filthy conditions falling well below the standards of a military hospital.

In the face of these problems, the DSCR decided that the situation at Speedwell was irretrievable and that the facility would be closed down. Military staff were re-assigned, civilians were laid off, and patients were moved to other facilities. The local Soldiers' Comfort Committee paid a final visit, bringing fruit and other gifts and holding a farewell dance (Evening Mercury, 4 Nov. 1920).

The Ontario government contemplated other uses for Speedwell, such as an insane asylum or merger with the OAC. In the end, they decided to return it to its former use as a prison. Local contractors were hired to put bars in the cell windows and make other preparations (Evening Mercury, 22 Nov. 1920). The theatre, which had served as a focal point for the amusement of returned soldiers, burned down in a mysterious fire during renovations (Globe, 28 Nov. 1921). The Speedwell Military Convalescent Hospital experiment was truly at an end.

Information about Speedwell and its institutional problems comes mainly from:

Durham, B. (2017). “The place is a prison, and you can’t change it”: Rehabilitation, Retraining, and Soldiers’ Re-Establishment at Speedwell Military Hospital, Guelph. 1911-1921. Ontario History, 109 (2), 184–212.

https://doi.org/10.7202/1041284ar