What might be called the "pre-history" of the postcard was recently outlined by Andrew Cunningham in Cardtalk (2021, v. 42, n. 2) the newsletter of the Toronto Postcard Club (of which I am a member). He explains that the idea of postcards as a specific and regulated piece of mail was introduced in Austria in 1869. Postcards could be sent through the mail just like letters but at a lesser rate (often half-price), the downside being that they could convey only short messages and afforded less privacy than regular mail.

The idea proved immediately popular and was soon copied elsewhere. In 1871, the Canadian government adopted rules allowing postcards in domestic mail. As abroad, "post cards" or "postals" were soon adopted by Canadians. Unlike later practice, postcards were then used chiefly for business correspondence, to request prices of goods or acknowledge receipt of payments, for example.

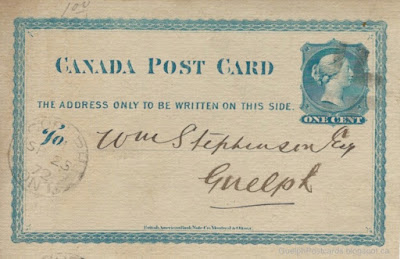

Here is an example of this type of card, sent to "Wm. Stephenson Esq." of Guelph on 25 Sep. 1872:

A brief inspection reveals that this item was indeed a novel form of mail, since it has strict instructions printed on it: "The address only to be written on this side." No chit-chat here! In place of a stamp, it has a portrait of Queen Victoria printed in the upper-right corner. This portrait assured the post office that the fee for mailing the card—one cent—had indeed been paid as part of the purchase price of the card. Since the right to print this "stamp" lay solely with the government, they were the only printers of these cards. Some very small type at the bottom of the card reveals that the printer contracted for the job was the "British American Bank Note Co., Montreal & Ottawa."The back of the card could hardly be plainer: It was a complete blank—write whatever you like. This may sound potentially exciting but most messages are disappointinly uninspired. Here is the back of the card sent to the Mr. Stephenson:

The message says:Deeds to you & Fleming duly executed. When will you & he be in to complete the purchase. W.M. Merrit // Sept. 25/72Short and to the point—businesslike. Indeed, the point of the card is apparently to further a real estate transaction. Let's see who was in on the deal.

Mr. Wm. M. Merritt was a Guelph lawyer. He studied law in Toronto and was called to the bar in 1868, at which point he took up practice in Guelph in the firm Dunbar & Merritt (Globe, 1 Apr 1898). He specialized in commercial law, so handling the deed in a real estate transaction was right up his alley. So, it appears that this postcard was sent from a Guelph address to another one—a short trip!

The year after he sent this postcard, Mr. Merritt moved back to Toronto, where he remained for the rest of his life. Even so, Guelph seems to have made an impression. He returned briefly in 1876 to marry local girl Miss Elizabeth Robertson, in what the Mercury (23 Feb) described as a notably fashionable wedding.

The "Fleming" mentioned in the postcard was likely Mr. George Fleming, a recently retired farmer. Mr. Fleming was an early settler of Guelph, having emigrated from Paisley, Scotland around 1836, when the former was still mostly a set of modest, log buildings (Mercury, 6 Dec 1876). For 32 years, he farmed a 100-acre lot a short distance east of town and then relocated to a residence on Berlin st. (now Foster Ave.) upon retirement.

It seems that shortly after his arrival, Mr. Fleming was the victim of disrobement (Mercury, 12 Aug 1868):

Guelph Police Court.Perhaps this incident could be taken as a compliment to Mr. Fleming's good taste in shirts.

…

James Fitzgerald was charged with the theft of a shirt from Geo. Fleming. He took it off the clothes line and put it on, and when the Chief Constable caught him he became pugnacious. At first we was for having the case tried at the County Court, but after the witnesses were examined he thought better of it, pleaded guilty, and consented to its being disposed of summarily. He was sent to gaol for a month at hard labour.

The recipient of the postcard was Mr. Wm. Stevenson, an important figure in Guelph's early days. Mr. Stevenson was born in 1817 near Thrumpton Hall, Nottinghamshire and immigrated to Guelph at the age of 20, at about the same time as Mr. Fleming. In religion, he was an active Methodist. He and James Hough were the prime movers behind the organization of the Norfolk Street Methodist Church in 1836, and he served as a preacher there from 1841.

(Norfolk Methodist Church, Guelph, ca. 1910., printed by the International Stationary Co.)Wm. Stevenson took quite an active part in the governance of the city. He was a Town Councilor in 1851 when Guelph became an incorporated town, separate from the surrounding township. He also served as town alderman (Councilor) in 1854, 1872, 1879, and 1880–1884. In 1885 and 1886, he was Mayor of the Royal City. One of his accomplishments in that time was organizing the Guelph Junction Railway, which connected the city with the Canadian Pacific Railway, thus providing some competition with the Grand Trunk Railway. While this connection helped the commercial interests of the city, its adoption of the Priory as a station set that building on the road to ruin, an outcome that Mr. Stevenson certainly did not anticipate nor would have approved.

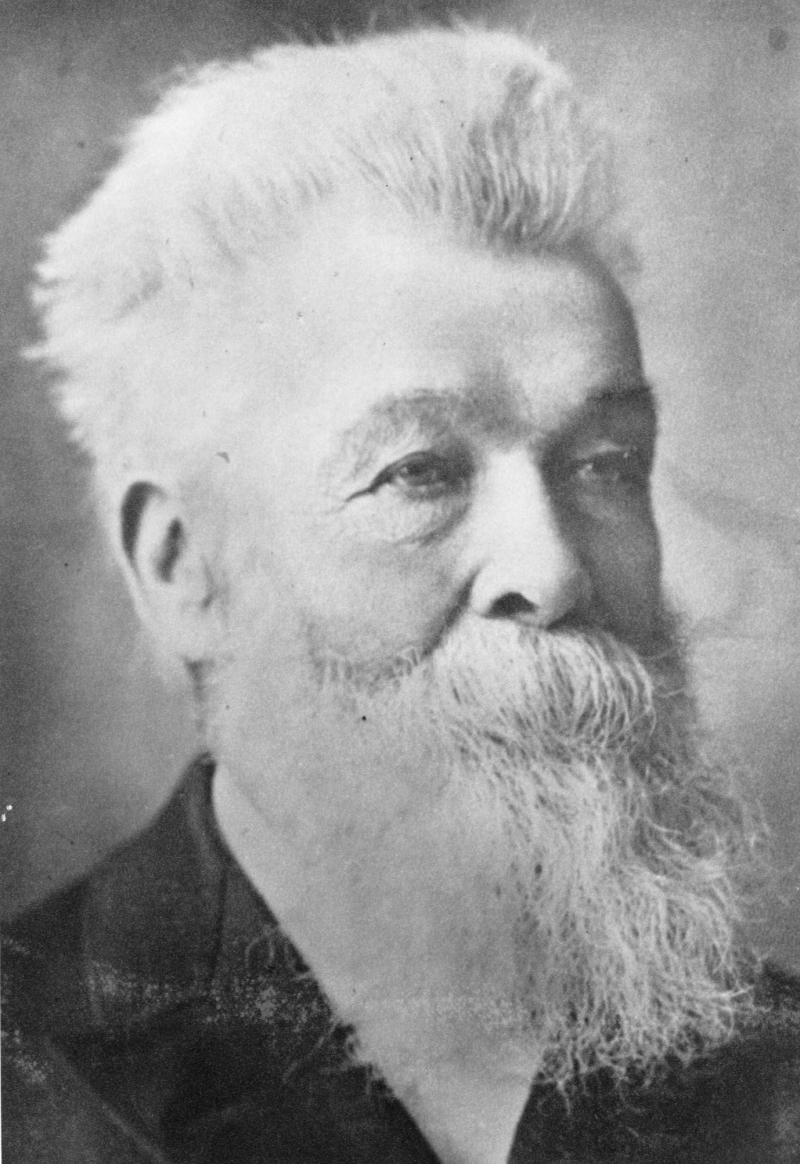

("William Stevenson," perhaps at the time he served as Mayor; Courtesy of Guelph Public Library Archives, F38-0-4-0-0-4.)Apparently a fan of reading and education, Mr. Stevenson also served on the Board of Education and took an active part in the founding of the Central School which competed with the Church of Our Lady for attention on Guelph's downtown skyline from 1876 until its replacement with a more modest structure in 1968.

("Central School, Guelph," printed by A.L:. Merrill, Toronto, ca. 1910.)Did I mention that Mr. Stevenson had a day job? He was a "nurseryman," that is, he grew and provided plants and trees to order. An ad from the Mercury (13 May 1874) gives an idea of what was on offer:

In 1872, when the postcard above was sent, Mr. Stevenson made a number of entries in Guelph's Central Exhibition, which was his usual practice. The Mercury (4 Oct) records that he won prizes in a number of categories, including Gravenstein apples, pears (variety and Bartlett), grapes (Adirondac, "ereveling," Hartford), and melons (scarlet flesh), not to mention his first prize showing in floral design.All of this work was carried out at his ample residence of "Maple Bank," at the corner of Grange and what is now Stevenson Street (yes, named after Wm. Stevenson).

(The location of Wm. Stevenson's nursery and Maple Bank in Wellington County Atlas, 1877.)The house itself was built sometime in the 1850s and is quite a nifty example of the Gothic Revival style in Ontario.

("Maple Bank," ca. 1960; Courtesy of Guelph Public Library Archives C6-0-0-0-0-466.)Happily, Maple Bank survives today and can be glimpsed from Grange street, as in this Google Street view scene:

Here is a picture of the Stevenson family, posed at Maple Bank, ca. 1860:

("Stevenson family," ca. 1860; Courtesy of Guelph Public Library Archives, F38-0-14-0-0-473.)In the back row stand Wm. Stevenson next to his second wife, Isabella, with Ephraim in behind. The girls are probably Miriam, Laura, Belvedera, Caroline, and Clara (ages, 10, 8, 6, 5, and 1, respectively, in the 1861 census). Given that Clara appears to be about 4–5 years old in the photo, it was likely taken around 1865.

Among Guelph history buffs, Mr. Stevenson is also remembered for the brief reminiscences he delivered in a speech in 1877. It follows the usual form of dates, names, and brief recollections, which the reader would like to know more about. For example, here is his brief recollection for 1854:

In October of 1854, about a dozen of the best stores on Wyndham and Macdonell Streets were burned down, causing a loss of many thousand dollars. About this time the town limits were enlarged, much to the disgust of those parties included in the new limits.Why were the new Guelphites so disgusted, and what form did their distaste take? It would certainly have been nice to know more of Mr. Stevenson's thoughts on the matter, particularly since he was a town Councilor at the time.

In any event, our humble postcard serves to remind us of one of the influential figures of Victorian Guelph.

Wm. Stevenson died on 6 June 1899 at the age of 81 and is buried at the Woodlawn Cemetery.

It would be remiss of me not to mention that some of the Stevenson children became noted figures in town. Ephraim Stevenson was a member of the Guelph Maple Leafs baseball club that held the semi-professional world championship in the early 1870s.

In a reminiscence about his early years in Guelph, Frank Coffee describes his memory of the team in these words (Mercury, 26 Oct 1918):

The original Maple Leafs had won a Canadian championship; Jim Nichols, Bill Sunley, Eph. Stevenson, Johnnie Colson, Tommy and Billie Smith, Jack Goldie, Kenneth Maclean, Harry Steele, were names to conjure with, as in successive seasons they held, against all comers, the championship emblem—the first silver ball.I have yet to find a labelled photo of Ephraim in his Maple Leafs uniform but I think that this photo from a collage assembled in 1871 is a good match for the young man posed on the porch of Maple Bank above: (Detail from "Maple Leaf Baseball Team, 1871." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 1979X.00.762.)

Despite his prowess at baseball, Ephraim's calling was to be a Methodist clergyman.

William and Isabella's youngest daughter, Maud, achieved fame as a singer. A paragraph from a short biography provides some details of interest:

The Toronto Globe of November 4, 1899, carries an account of Miss Stevenson and mentions that she is known from coast to coast across Canada for her concert work. Also in London, England, she received flattering comments on the tone and quality of her voice as well as the keen dramatic instinct she possessed. She was, it said, able to sing with equal ease, the most difficult classical selections and Scottish ballads. Her soprano voice had a magnificent range and sweetness. She was called "Guelph's sweet-voiced singer."There is a portrait of her from ca. 1880 in a Notman photograph in a dark outfit and looking rather severe: She is identified by her married name of Maud Stevenson Pentelow. (Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2014.84.1066.)

Maud's older sister Clara was also an excellent singer, though she did not enjoy an international reputation. Nonetheless, she is commemorated in the name of Clara Street in the St. George's Park neighbourhood. The reason is not clear to me, although it may not be a coincidence that Clara was the second wife of local mover-and-shaker J.W. Lyon. Anyone who knows the story is invited to fill it in in the comments below.

A portrait of the children of William and Isabella Stevenson, taken ca. 1925, is shown below:

(Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, Grundy 12.)From left to right, the figures are Belvedera, Clara, Carolina, Minnie (Miriam?), Maude, Rev. Ephriam, and Laura.

Sources consulted for this post include:

- Sudbury, H. "Stevenson, William." Publication of the Guelph Historical Society 1965. 5,9: 1–2.