No soothing syrups should be given to babies, and she emphasized the danger of allowing too many people to kiss babies.This seems like sound advice, especially considering that "soothing syrups" of the era could well contain uncontrolled amounts of narcotics or alcohol. Soothing? Yes. Healthy? Not so much. The prohibition on kissing probably reflects the recent ascendance of the germ theory of disease, on which illnesses were held to be caused by infections of microscopic organisms, a theory that still prevails today. ("Massey Hall and Library, O.A.C.," #173 of the International Stationary Co. series on Guelph, ca. 1910.)

Miss Watson, principal of the Macdonald Institute associated with the OAC, articulated advice particularly a propos of the holiday season:

"Don’t train children to drink tea, coffee, or any other stimulant. Don't teach them to eat highly-seasoned foods, and up to fourteen years anyway forbid pickles and highly-seasoned foods, and forbid rich foods, such as pastry, puddings and cakes.” Miss Watson stated that the time was very opportune for speaking of feeding children, as a great deal of the sickness which followed Christmas among children was due to the stuffing on Christmas day. Instead of giving children plum pudding and mince pie, she suggested that a pretty dessert be prepared, plain, but wholesome, which the children would enjoy.No soothing syrups, no stimulants, no pickles, no stuffing, no pastries, no cake, and no pie. And no fun.

The Women's Institute was (and remains) an association that advocated for women's issues, founded in 1897 in Stoney Creek by Adelaide Hoodless. Branches quickly spread throughout the Dominion and abroad. Ms. Hoodless was also the prime mover behind the foundation of the Macdonald Institute, which aimed to teach young women skills they would need to run modern households. It was hoped that such training would help to stem the tide of young women leaving rural Canada for its cities, where jobs as bookkeepers, store clerks, telephone operators, and so on, beckoned them away from the farm.

(In fact, it was just at this time that the population of Ontario went from being mostly rural to mostly urban, with more residents living in cities than outside of them.)

Besides domestic issues, the convention included some remarks on the place of women in political life:

Mr. C.C. James ... charged the women to look after the proper training of children, and instead of dabbling in politics, endeavoring to break up men’s meetings or agitating for suffrage, to see that the home life was made as educating as possible.Ten years later, women gained the right to vote for the first time in Canada.

The postcard craze of the era continued to gain momentum, with many Guelphites sending postcards to touch base during the holiday season. One such card featured a picture of the new Carnegie Library in Guelph, the front of which was featured in an earlier blog post on that structure.

Obviously, this card was not designed to be a holiday card but it could do the job with a suitable message, in this case from "B.P." to Mary in Lifford, Ontario: The message says:Guelph Ont, Dec 5th/07 // Dear Mary:— I don’t think I sent you a card like this one before. it is a pretty place both inside and out[.] Wishing you a Merry Xmas and a Happy New Year, B.PIt sounds as though B.P. and Miss Mary Staples of Lifford had been exchanging postcards, a common way for children and adults of the time to see images of places they probably hadn't been and to have fun amassing a collection of their favorite cards. (A hobby that can be carried on today, I should add!)

So, what kind of Xmas did Guelph have in 1907? Was it merry?

From the cooking advice given by Miss Watson, it might seem like the children of the Royal City did not have a good time. However, we learn that some managed to entertain themselves in a time-honored fashion by toboganning down the sidewalk on Neeve street after a big snowfall. Though fun for the participants, the practice did not meet with general approval (Mercury, 17 December):

Naturally some objections were raised, and the boys were asked to keep off the sidewalk, with the result that retorts were made, advising the sojourning of the parties in a land where snow is not known and sleds utterly useless.Police were summoned and four of the boys appeared before the magistrate, who let them off with a warning and an admonition to have their parents administer justice via a hickory stick. The paper does not record if this was done.

In another sign of times, a group of young women were observed walking through the town in male garb (4 December):

A couple of charming young ladies last night made their debut in that attire, consisting of Christy, trowsers and coat, which is usually conceded to be part of the male make up. The young lady gentlemen were from one of the local hotels and, with their hands in their pockets, curls stuck under Derbys, and chaperoned by a couple of men friends, they made a parade of the main streets to the astonishment of the natives who happened to be abroad and the entertainment of the young men on the street corners. This disguise was not carried so far as to include the wearing of overcoats, and the masqueraders could not have found it pleasant. They were thoroughly chilled.Presumably, they were not attending the Women's Institute convention. But, although chilly, it does sound somewhat merry.

The weather in December 1907 was generally quite wintery. There was quite a blizzard on the 14th, which blew snow up into high drifts and immobilized the streetcar system for several hours. The street railway prepared and opened up the outdoor rink that it usually operated on Howitt's pond, near the the system's main building. The same site featured change rooms and a toboggan slide.

(The Petrie Rink, Gymnasium and Baths; Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums 2014.84.2.)The team of the Guelph Hockey Club prepared for a new season. Local players worked on their skating legs on the frozen pond at Goldie's Mill. The Royal City rink, at the intersection of Gordon and Wellington streets, had recently been enlarged and was ready for more games and up to 1,600 spectators. (The rink had begun life as the Petrie Athletic Park in 1897, was turned into a cream separator factory in 1901, and then back into a recreational facility earlier in 1907.)

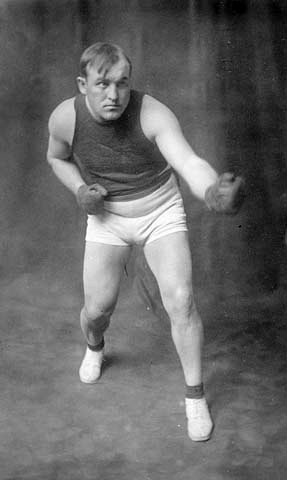

(Tommy Burns, ca. 1912. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada 3191889.)Besides winter events, Guelph was also linked, albeit somewhat tenuously, with the world heavyweight title boxing match in London, England, between "Gunner" Moir and Tommy Burns. Burns was born as Noah Brusso in Hannover, Ontario, and became a professional boxer in 1904, adopting the Scottish moniker "Tommy Burns" perhaps for professional reasons. He clearly had a talent for it and became world champion in 1906. On 2 December 1907, he fought British boxer "Gunner" Moir in a title defence. Though Moir was the bigger man with a harder punch, Burns's "ringcraft" served him well and he soundly defeated Moir by a KO in the 10th round.

A film of the whole fight can be seen on YouTube, along with an added commentary track. There is also a video of selected highlights, which is much shorter.

The connection with Guelph? In February, 1907, Burns had been to Guelph to put on an exhibition of boxing at the Royal Opera House with his sparring partner Jimmy Burns of Toronto. Burns was a former resident of Galt, so he was able to drop by there to visit his parents during the outing.

In addition, the Toronto Globe (2 December) reported that Burns sent the following message just before the fight to Alderman Higgins of Guelph, manager of the Royal Opera House: "Am defending the world’s championship against Gunner Moir, and will fight to bring home the money and honors.” So, it seems that Burns retained a connection with the Royal City after his recent visit. No doubt, many Guelphites read the account of his fight with great interest.

("The Bell Organ and Piano Co., Ltd., Factory, Guelph, Ont." published by Valentine & Sons Publishing Co., Ltd., ca. 1905. Courtesy of the Keleher collection. The front of the Royal Hotel can be seen to the right of the factory, facing onto Carden street. Jubilee Park is visible in the foreground, now the site of the VIA station.)One thing that stands out to anyone reviewing the events of Xmas time in Guelph, 1907, is the number of big fires. On 5 December, a "dangerous" fire broke out in the Royal Hotel, next to the Bell Piano factory on Carden street. The fire started in the cellar and soon seemed to have hold of the entire building. It was said that smoke was soon pouring out every window. Business travelers, with whom the hotel was popular, immediately smashed many of the ground floor windows to eject their trunks and other wares. One man named Tracey had 14 trunks with him, all of which he managed to save in this manner.

A number of women were trapped by the smoke on the third floor. One made ready to throw herself out but was persuaded to wait for a ladder rescue. This was duly accomplished by Assistant Chief John Aitkens of the London fire brigade, who, for whatever reason, happened to be on hand. After the fire was doused, Aitkens went to the cellar to investigate its cause, when he was arrested by a police constable! Happily, he was well known about the town and was quickly released.

Though damage was considerable, no one was seriously hurt.

(The Taylor-Forbes factory, as seen looking northward from the Neeve street bridge, from a real photo postcard dated 1919; courtesy of the Keleher collection. The Guelph standpipe can be seen in the background.)On 9 December, there was a blaze in a shipping building of the Taylor-Forbes plant on Arthur street. Mr. James Taylor noted smoke pouring from the structure and called it in to the fire department. The fire was quite intense as a pile of seasoned timber in the structure ignited and made for some very dense smoke. It was difficult for the fire fighters to get into the building, so they cut holes in the roof and gable ends to train water on the flames.

The fire was put out in a couple of hours but the company lost quite a bit of finished products, mainly lawn mowers, radiators, and similar items.

Another serious fire occured in St. George's Square in the boot-and-shoe store of "J. Dandeno" on 22 December. Mr. Dandeno had been cleaning up and oiling the floor, a measure taken to keep wooden flooring in good shape. He left a lit lamp on the landing of the stairs when he exited through the rear door. When the door slammed shut, it caused a rush of air that upset the lamp, which tumbled down and set the floor oil on fire. The flames quickly climbed the stairs, threatening to set the whole building—and its neighbors—ablaze.

(East side of St. George's Square, ca. 1910. Joseph Dandeno's shoe store would have been where Alex Stewart's drug store is in this photograph. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.32.4536.)Mrs. Dandeno ran up the stairs, through the flames, to rescue the children, which she was able to do through a rear window, with the assistance of some passers-by. She and two children were slightly burned and treated at the hospital.

The fire brigade had the fire out in about 45 minutes, and managed to save the surrounding buildings from much damage. Still, the Dandeno's losses were about $6,400, only half of which was covered by insurance.

This J. Dandeno was very likely Joseph Dandeno, a local boy who had worked as a piano finisher at Bell's Piano factory since about 1889. Only in the 1908 city directory is he listed as associated with a shoe store, suggesting that he had only recently gone into the trade before the fire struck. Evidently, the loss and shock were enough to prompt Dandeno to move to Providence, Rhode Island, the next year, where he lived for the remainder of his life.

("Photograph, Rotary Club of Guelph, Lionel O'Keeffe, 1921." George Scroggie is standing fifth from the left in the front row. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2014.84.282.)Despite these serious fires, Guelph escaped a general conflagration. However, it was consumed by an unusual scandal that year. It came to light that month that George Scroggie, the City Treasurer, was collecting two rents for one of the residences that he owned in the city. In brief, Scroggie rented out a modest residence on Durham street to a Mrs. Fisher, an elderly black woman who was described as "a well-known character" (Mercury, 20 December). Mrs. Fisher was destitute and relied to a large degree on the generosity of her friends and neighbors. As such, her rent of $4/month was covered by the City's Relief Committee. However, Mrs. Fisher was also staunchly independent and preferred to pay her own way as much as she could manage. As such, she had been paying some rent money to Scroggie, even though the city covered the full amount.

So, it seemed as though Scroggie was collecting rent twice, once from the city and again (in part) from the destitute Mrs. Fisher. Naturally, when this situation came to general notice, it looked bad for Scroggie. The Relief Committee of the city council investigated and learned the particulars. They learned that Mrs. Fisher was perfectly aware that her rent was paid by the committee but was determined to contribute to it as much as possible. They learned from Scroggie that he was saving the money that Mrs. Fisher paid to him in this way with the idea of remitting it to the city at the end of the year.

Was this odd situation even a matter for the city government? After all, rent for the residence was paid by the committee to Scroggie as per their express arrangement. If Mrs. Fisher wanted to pay him further money out of her own pocket, knowing that her rent was fully covered, perhaps that was simply her affair. However, the committee felt it had to do something, as rumors about the situation had been spreading like wildfire.

When the committee offered to pay Mrs. Fisher the money she had given to Scroggie, and which he had remitted to the city, she refused (Mercury, 24 December):

The amount of these payments, about $20, which Mr. Scroggie has stated his willingness to pay, was offered to her, but she refused point blank to accept it. She is a very eccentric old lady, and independently maintains that she will be dependent upon charity no more than she possibly can.So, the committee arranged for the funds to put in the hands of a trustee to be used on Mrs. Fisher's behalf when the need arose. This arrangement met the approval of the editor of the Mercury, who remarked that she would certainly need the support before the winter was out. ("Winter Fair Buildings, Guelph." Published by Henry Garner Living Picture Postcard Co., Leister England; posted in 1909. Now the site of the Market square; note the old city hall at the left.)

Since its founding in 1827, Guelph was a central point in local agriculture, a role that was enlarged with the founding of the OAC in 1874. In 1889, the Royal City became the permanent site of the Ontario Provincial Winter Fair, in which the finest live stock, poultry, produce, and other agricultural items were displayed and judged. The year 1907 was no exception, with the Winter Fair building on Carden Street (now the site of the Market square) hosting a panoply of meetings and events.

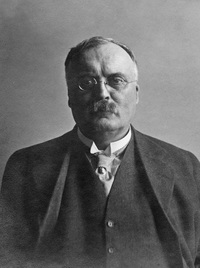

("Sir Adam Beck," Watercolour, gouache, gum arabic, on ivory, by Gerald Sinclair Hayward, 1902. Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum, 993.209.1.)Perhaps the biggest draw was the speech given by the Hon. Adam Beck. Although the meat of his speech was to encourage Ontario agriculturalists to pay more attention to horse breeding (Beck was a enthusiastic amateur breeder), he could not help but mention his support for the plan to connect the region's cities to a single grid, by which electricity generated at Niagara Falls would be distrubted throughout under the auspices of a government corporation. Educated at the nearby Rockwood Academy, Beck had recently been appointed the first chairman of the Hydro-electric Power Commission, dedicated to this purpose. Guelph, like most cities in the region, was about to vote on by-laws that would commit them to the scheme. Government control, Beck argued, would ensure that the resource was developed and made available with the public interest at heart, rather than as a money-making scheme of private providers. The next month, Guelph, along with almost all municipalities in the region, voted resoundingly in favor.

Despite the success of the Winter Fair, the biggest agricultural news that winter in Guelph was the victory of the OAC stocking judging team at the International Livestock Show in Chicago the previous month. A team of students from the OAC won the overall event there for the third year in a row, which entitled them to take permanent possession of the Spoor Trophy, in the form of a bronze bull. The win was considered a national victory, which I have described in a previous post.

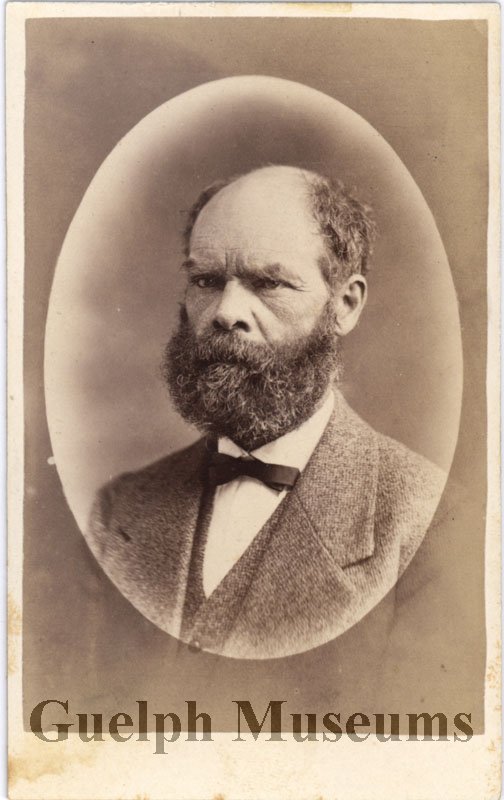

The real photo postcard above shows students from the OAC celebrating their triumph by painting the Blacksmith Fountain in red and white, the OAC colors, during a victory parade. The Blacksmith retained his new livery for the holidays, though it was soon removed by a city crew. ("James Gow," ca. 1880. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, M1991.9.1.149.)Guelph received an item of sad news during Xmas 1907 as well. Mr. James Gow, described by the Mercury (21 December) as "one of the most lovable men who ever lived in Guelph," passed away at his residence in Windsor, Ontario (Mercury, 21 December). Born in 1827 in Glasgow, Scotland, Gow had emigrated to Canada in 1851, settling first in Hamilton but then moving to a farm in Eramosa. In town, he struck up a partnership with Peter Gow (not a relation or, at least, an immediate one), in the form of P. & J. Gow, tanners and leather merchants. In 1866, the partnership was dissolved and Gow had a storehouse built on Huskisson street (now Wyndham street south) to carry on the business in his own name. However, he was then appointed to the office of Collector of the Inland Revenue in Guelph.

Ten years later, he was transferred to the office at Windsor and then made Inspector of the Windsor District and Dominion Inspector of Distilleries, an appointment he held until retirement in 1902. Although he had been away from Guelph for some 30 years, we are told that his inspections brought him regularly to his old haunts and that he kept in close contact with old friends and family members who remained in the Royal City.

On the whole, it seems that Xmas and New Year's in Guelph in 1907 was merry enough, though not remarkably so. It was neither especially memorable but not without notable news and events. Perhaps the season is epitomized by the following item from the Mercury (28 December):

Drank 21 beersNo doubt, speakers with the Women's Institute would not have approved but such were the spirits of Xmas in Guelph in 1907.

This is the story which is going the rounds today. The employees of a certain factory last night decided to test the drinking capacity of one of their number—a colored gent. Accordingly they hied themselves to the nearest dispensary of warming drink, and then this man of mighty thirst got on the outside of 21 beers—not small beers, or short beers, or ordinary beers, but 21 big pint schooners of lager. He walked home afterwards but was not at work today.

Merry Xmas and Happy 2025, Guelph!