Dear Aunt and all—Just a card to let you know I arrived here safely. I haven’t time to write a letter for I am working day and night. This is the old Boys reunion here this week and I am busy all day and at night[.] we have a booth and I have to show the guests over our building. I am so tired I can hardly wiggle but it is only for a week & it means extra dollars for me. Don’t write until you hear from me for the O.A.C. office is closed this week. Bye Bye Love Edith. // I was for a ride in an airplane on Sunday.The card was addressed to Mrs. Melvin Wolfe of Straffordville, Ontario, in care of Frank Wolfe, and was postmarked on 3 August. (Mailed and delivered on the same day!) ("Main Building, O.A.C., Guelph, Ont., Canada," published by Valentine & Sons United Publishing Co., Toronto, ca. 1925. Postmarked 3 August 1927.)

The card was published by the Valentine & Sons United Company of Toronto, one of Canada's biggest postcard producers. The image on the front was a view of the Main Building (replaced by Johnston Hall in 1931). Perhaps Edith selected the card in honour of her association with the Ontario Agricultural College (O.A.C.), which she mentions in her missive.

(Reverse of the card above. Note the special Guelph Old Home Week cancellation logo in the upper right corner.)Another sign of the importance of the Old Home Week (also known as the Old Boys' Reunion) was that the postcard displayed a special logo in the cancellation mark, which says, "Guelph Centennial Old Home Week Aug 1–8." The post office would apply these special marks to celebrate events of particular significance, of which the Week was one.

The idea of an Old Home Week was for a town to put on a big bash and invite former residents to party in their old haunts and reconnect with old friends, while spending freely to support the local economy. Guelph had had its's first Old Home Week in 1908 and its second in 1913. Understandably, plans for a third were postponed in the wake of the Great War. But, with Guelph's Centennial year of 1927 approaching, authorities and citizens decided it was time to stage another.

The accustomed format of Old Home Week in Guelph was daily parades and themed events in Exhibition Park. The 1927 edition repeated this format. Each afternoon, a parade led from the (old) city hall to the park, led by musicians such as the Guelph Musical Society band.

("Guelph Centennial Old Home Week, 1 August 1927." The view overlooks the parade making its way through St. George's Square, with the central arch visible on the right of the picture. The float in the foreground appears to be the Guelph Mercury, float number 87, signed "Weekly Pioneer Printing Office." The Post Office float, float number 91, approaches in the background. Local photographer Lionel O'Keeffe published a series of photographs of the "Mammoth Centennial Historical Street Parade." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2022.42.31.)However, a special "Mammoth Centennial Historical Street Parade" with 112 floats was mounted in the morning of 1 August. The floats formed queues off Gordon Street along Wellington, Surrey, Fountain, Nottingham, and Essex Streets. From there, they paraded along Carden Street past the (old) city hall, up Wyndham Street to Woolwich and thence to London Road, then along London Road, down Dublin Street, along Suffolk to Norfolk Street, and thence to Quebec Street and the finishing point in St. George's Square (Mercury, 28 July 1927).

("Guelph Centennial Old Home Week, Aug. 1, 1927. O'Keeffe Photo Guelph." This photo shows the Colonial Whitewear float, float number 41, probably waiting on a side street to join the parade.)Most of the floats were sponsored by local businesses, ranging from old standbys like the Robert Stewart Lumber Company and the Bell Piano & Organ Company, to more recent arrivals like the Northern Rubber Company and Biltmore Hats. Organizations like the Fire Brigade, the Model Dairy, and the YMCA were also represented. Naturally, entertainment was provided by outfits like the Guelph Musical Society, the Toronto regimental pipe band, and—appropriately for the Jazz Age—a jazz band. Entertainers such as the Toonerville Trolley (inspired by a popular comic strip called The Toonerville Folks), and several comics kept the merriment going.

(Postcard showing "The Centennial Arch in St. George's Square during Centennial Celebrations, 1927." Light bulbs are visible on the arch and its supports, suggesting how it would have appeared at night. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2000.21.7.)The Royal City dressed up for the occasion. Flags and bunting were flown over streets and strewn across facades. Special illumination was provided with electric lighting. Over 25,000 feet of wiring was used to position 10,000 vari-colored light bulbs throughout the main streets and nearby dwellings. The new stone towers of the Church of Our Lady were lit up by the powerful rays of flood lights, to shine like twin beacons in the night sky. St. George's Church, the (old) City Hall, the Post Office, and the recently completed Cenotaph all got similar treatment. It may have become difficult to tell night from day in the old town!

(The centennial arch across St. George's Square can be seen across the streetcar tracks with the old Post Office in the background in this real photo postcard. On the bacck, Ms Vera S. informs Elenor Klepd of Cleveland, Ohio, that "Having a fine time in the old home town. This is a picture of some of the decorations at the Post Office." Postmarked 8 August 1927.)Especially notable among the town's decorations were the centennial arches. Numbering 10 in all, large archways bestrode several routes into town as well as across Wyndham street by the (old) city hall and in the middle of St. George's Square. The latter two were of special magnificence being among the city sights illuminated for the celebration.

("Wyndham St., Guelph, Ont." published by Rumsey & Co. ca. 1930. Courtesy of the Keleher Collection. This is the only regular-production postcard featuring an Old Home Week 1927 image that I am aware of.)The arch spanning lower Wyndham street had the words "The Royal City extends you 1000 welcomes." In addition, one side bore text denoting "Guelph Centennial" while each displayed the auspicious dates, "1827" and "1927."

The arch in St. George's Square spanned the streetcar tracks that yet ran down the middle of the street, while each supporting arm was itself another arch. The main arch was topped with a crown and the "Guelph Centennial" logo, while each supporting arch repeated "Centennial," the dates "1827" and "1927," as well as the reminder that the event was "Old Home Week, Aug. 1–6."

("Castle Centennial Archway, 1927." This arch stood just east of the entryway to the Ontario Reformatory on York Road. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2000.12.4.)A third arch was placed across York Road near the entrace to the Reformatory. This arch was distinguished by a castellated top featuring a maple leaf and the sign "Welcome," as well as the thematic "Guelph Centennial" and "1827" and "1927." Signs on the pillars bore the familiar "Old Home Week, Aug. 1–6." It is notable that this arch was placed at the entrance to the Reformatory even though that institution was outside the city limits of the day, which went only as far east as Victoria road. It seems the Royal City looked upon the Reformatory as being part of Guelph, culturally if not formally.

Photos place other arches at the Ontario Agricultural College (Dundas Road, now Gordon Street), Riverside Park (Elora road, now Woolwich Street), Eramosa Road, Dundas Road bridge (now Gordon Street), and Waterloo Avenue. I would guess the two remaining arches were across Paisley Road and the Kitchener road (now Speevale Avenue west).

("Ontario Agriculture College, Centennial Celebrations Arch." Dundas Road (now Gordon street) looking north. Johnston Green is visible on the right and the Ontario Veterinary College on the left. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.52.30.)All these celebratory arches must have assured visitors that the Royal City was to give them the royal welcome!

("Arch entering city, 1927." This arch spans the Elora road (now Woolwich Street) at the entrance to Riverside Park. The entranceway to the park is visible on the left and streetcar tracks can be seen beside the road on the right. I assume that the arch features greenery and logs tied around its supports to suggest the rustic fittings of the park next door. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2000.12.3.)The headline event held in Exhibition Park was no doubt the Great Historical Pageant. At 8:15pm on 1 August, a cast of 500 performers, along with a chorus of 200 singers, staged a pageant in front of the grandstand that rehearsed the story of Guelph. Although the Guelph Mercury for August 1927 is sadly missing, the script of the pageant is amply described in a program for the Old Home Week. The event kicks off with the arrival of Miss Guelph (Miss Roberta Armstrong) to a fanfare of trumpets. Accompanied by her attendants, Patriotism, Courage, Achievement, Liberty, Pride, Stability, Honor, Beauty, Health, and Peace, she addressed the multitude:

Fellow citizens of the province of Ontario, and the Dominion of Canada, in the name of the goodly inhabitants of this city and in honor of our celebration this evening, I bid you a most cordial welcome. ...Anon, Miss Canada (Miss Claire Little) delivers her reply:

Miss Guelph, in the name of Canada and her Fair Provinces. I acknowledge this your welcome. With pride we recognize in Guelph one of the brightest gems in the crown of our Canadian Achievement. We are happy tonight to receive your welcome to this great assemblage in honor of those sturdy men and courageous women who here began a march of progress, the direction of which has ever been forward.("First Wedding Float Guelph Centennial Parade, 1927." A buggy driven by well-dressed footmen, conveys a small party, perhaps the bridge and groom, shaded by parasols, pulled by a horse and donkey, no doubt signfying the happy state of matriomny. The float is moving past Waterloo Avenue up Wilson Street. A note on the back of the photograph states, "A burlesque of the first wedding, one of many comics." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.52.4.)

With this, Misses Canada and Guelph turn to view the company before them unfold the march of progress that was the history of Guelph. For the sake of brevity, I will simply list the episodes here: (1) The dawn of creation, wherein the land, sky, flowers, and water are shaped and moulded, (2) The Indian, wherein "the primitive life of the Indian" is imaginatively depicted by performers in costume, (3) the founding of Guelph, wherein John Galt and company felled an elm tree and dedicated the site to the royal family, (4) the heroic advancement of Pioneer Manhood and Pioneer Womanhood in the face of Fever, Famine, and Death, (5) the first school, wherein pioneer children were taught by an American named Davis though, regretably, "Davis' intellectual acquirements did not go much beyond the 'three Rs' and he was soon released," (6) the first railroad, wherein the first train steamed in to Guelph and MPPs played a little joke on the locals by presenting the MPP for Lanark as the Governor-General, resulting in "considerable agitation," and (7) the first wedding, wherein Kitty Kelly was pressured into marrying Christopher Keough earlier than she had planned in August 1827. Last came a Masque of Nations.

("Eramosa Road arch." This leafy-looking arch says "WELCOME" in big letters and seems to span the road near Queen street. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.32.40.)Of course, Exhibition Park was the site of many more events. For example, a packed program of track and field events was held. The headline event was probably the men's five-mile run, which was won by Harold Webster of the Hamilton Olympic Club. A number of women's events were included as well, an indication of the increasing regard in which women's sport was held at the time. In particular, there were competitions for women in the 100-yard dash and the quarter-mile relay, not to mention softball.

("Guelph Centennial arch on Gordon Bridge." This bridge was installed in 1892 and was the third span built at this location. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.32.38.)In fact, as the Hamilton Spectator noted with some smugness, Hamiltonians dominated at the events, prevailing over the locals and athletes from Toronto's West End YMCA (5 August 1927):

Combining their efforts, the Hamilton Olympic club and the Canadian Ladies’ club, of this city, accounted for major honors in the big track and field meet that was part of old home week at Guelph, yesterday afternoon. With the Olympic club boys looking after the sterner sex, the Hamilton girls made a clean sweep of the events for the fair sex, and altogether it was a good day for the local contingent.The bright spot for the home team was probably the youth's 1-mile run, which was won by local boy Frank Terry in 5 min., 35 3-5 seconds. ("Guelph Centennial arch: Waterloo Ave. car barns." The view looks towards downtown Guelph from Waterloo Avenue, just west of the street car storage sheds ("barns"). Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.32.37.)

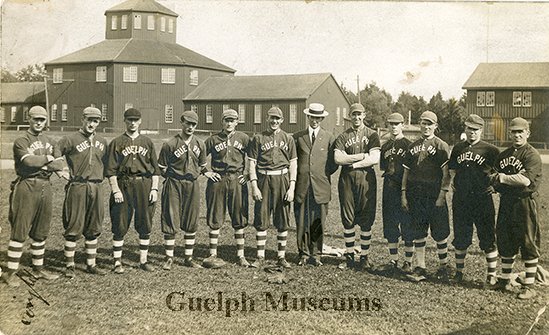

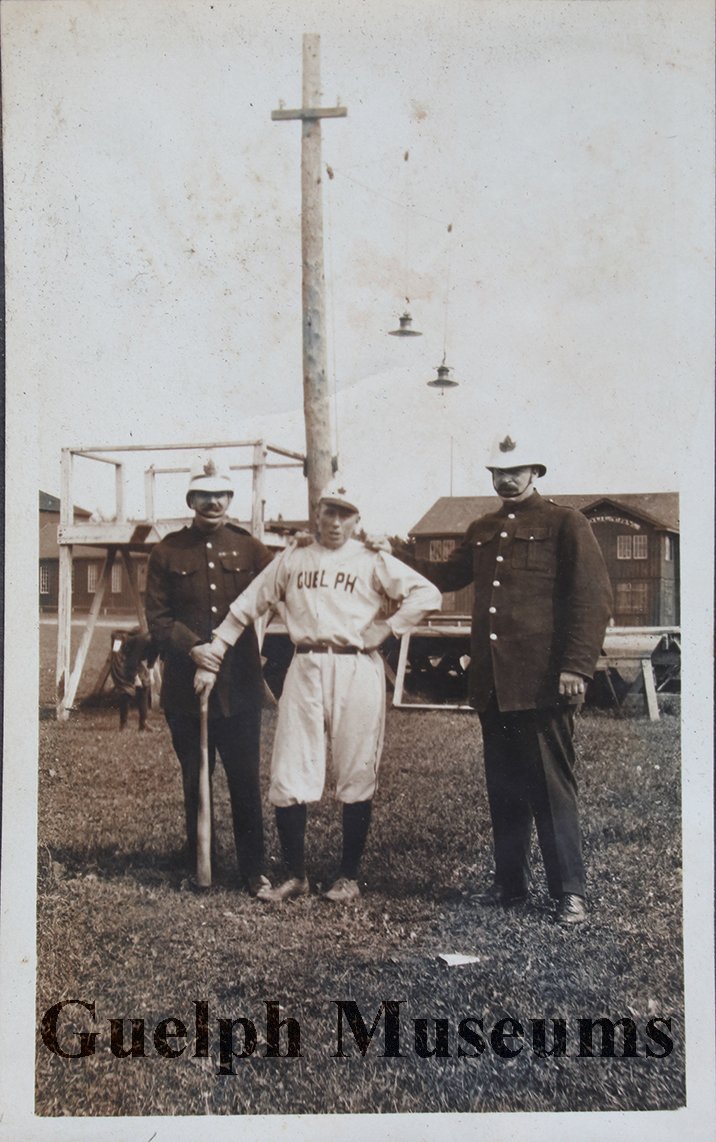

Naturally, baseball was a headline event for the Old Home Week. The junior league Guelph Maple Leaf team came through in style with an 8–5 win over the Tom Cats of St. Thomas on 4 August.

Of course, the big game was the contest in the senior division between the Maple Leaf team and the Terriers of Galt. The two teams had been competing for top honours throughout the 1920s, and they seemed to be headed for the league championship series later on. Unfortunately, the game was a "listless affair" consisting of lacklustre pitching and several fielding errors (Waterloo Record, 2 August). Still, the score provided some drama, with the local side overcoming an early deficit of seven runs to nearly defeat the visitors. However, Galt's reliever, "Friendly" Graham, was able to pitch his squad's team out of a Guelph rally in the ninth inning, leaving two runners on base, for a 13–12 win.

(Guelph and Galt did go on to meet in the Intercounty League champtionship in September but the Terriers came out on top. So, Guelph continued to just miss out on the championship it last won in 1921, against the Terriers.)

("Charles “Sandy” Alexander McHardy, baby contest, 5 August 1927." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2025.22.1.)Another interesting feature of the Old Home Week was the baby contest. For some decades, it had been common to enter babies in contests at agricultural fairs to be judged, presumably, in the manner of prize steers, with top honours going to the "bonniest" baby. We learn that 143 infants were entered into the Guelph contest in 1927. Winners in the six-to-nine-month division were Helen Georgina Green, of Belwood, for the girls and John Duncan, of Alton, for the boys (Windsor Star, 6 August). In the nine-to-twelve-month division, winners were Ann Bell Russell, of Mount Forest for the girls and Charles "Sandy" McHardy of Fergus for the boys. Each winner received a five dollar gold piece, with Charles McHardy receiving a special silver cup, presumably for being the bonniest big boy.

Although baby contests were positioned among the casual amusements available in the celebration, they did have a more serious purpose. They promoted awareness of child heatlh issues in an era when child welfare was threatened by diseases and child labour. Also, contests were used to promote the eugenic idea that some children were innately better than others. It is notable in this respect that the children entered into such contests, like the winners in Guelph, were white. Although Guelph had significant black, Chinese, and Italian communities, their children do not feature among the ranks of the contestants and winners.

("A jazz band playing in an Old Home week parade on Wyndham Street." Besides being in the Mammoth parade, the jazz band roamed the city during the week entertaining the old boys and girls wherever they were found. Courtesy of the Guelph Public Library, F38-0-9-0-0-19.)Not all the celebrations were held at Exhibition Park. Of course, parades, decorations, and special lighting were prominent in the downtown, especially along Wyndham street. Besides this, Wyndham street was host to the big masquerade dance held on August 2nd. After a parade mounted by the Guelph Humane Society, Wyndham street was cleared and an open-air concert held while the "old boys" and girls danced in disguise (Hamilton Spectator, 2 August). It seems that a good time was had and the event continued into the wee hours of the following morning.

("The Priory Model in front of City Hall during Centennial Celebrations, 1927." The Priory was the first house built in Guelph for John Galt. It was allowed to fall into ruin and was demolished the year prior to the centennial. This model may have been made from wood taken from the original structure. I believe this model was later installed in Riverside Park. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2000.21.8.)As crowds sizes grew during the week, the midway, initially sited at Exhibition Park, was relocated to the gap in Wyndham street that was left after the great fire of 1921, in which the Robert Stewart planing mill burned down. In 1935, this gap in the streetscape was largely filled by the Dominion Public Building, now occupied by the Wellington County Government. But, for a few precious days, it was one of he funnest places in the Royal City!

("Old Home Week," 1927. The centennial arch over Wyndham street with the (old) City Hall and Winter Fair building in the background. Courtesy of the Guelph Civic Museums, 2014.84.520.)Things did get a little out of hand. On Wednesday, shortly before midnight, attendees were treated to the performance of a snapped high-voltage overhead wire (Galt Reporter, 5 August):

Like a huge snake, spitting fire, a snapped trolley wire curled and writhed in the midst of a terrified crowd of street celebrants at the corner of Wyndham and Macdonnell streets shortly before midnight on Wednesday night. A Kitchener boy, about 20 years of age, had grabbed the rope which releases the pole of the street car, pulling it down to the roof of the radial and letting it go. The pole struck the wire, breaking it. The wire, striking the tracks and flaming with thousands of volts of current, whipped around the crowd but fortunately struck no one. The boy was captured after a strenuous chase and locked up for a few hours.There were also complaints about drunkenness. The same Galt Reporter quoted the Guelph Mercury as saying that some people were "indulging promiscuously and publicly with the contents of the bottle," resulting in "inconsiderate behavior" and "vile and profane language." ("Guelph Elastic Hosiery Co. Float, Guelph Centennial Parade, 1927." The float is passing Waterloo Avenue on its way up Wilson Street. The company is most noted for its reinvention of the jock strap, which is, sadly, no evident on the float. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.52.6.)

A similar complaint was noted in the Acton Free Press (11 August):

Children, who had never seen drunken men, had the sight cast in front of them continually. Numbers of young lads either secured what they thought was sufficient to make them tipsy, or tried to give that impression in their actions. Was there no bootlegging? We heard a rumor that said that when the Government store closed on Saturday and did not open until Tuesday that the stock of the bootleggers in a certain section was completely exhausted. We don’t want to give the impression that the celebration was nothing but a drunk orgy, but it is hard to be convinced that the Government Control measure is lessening the sale of or improving the control of booze.The Liquor Control Act had been passed only the previous June and the province was still in the process of setting up the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO) and its control of liquor purchasing. So, in the eyes of some commentators, the Old Home Week was an early test of this system and they were not impressed. ("Toronto Regiment, Guelph Centennial Parade." The formation is marching up Huskisson Street (now Wyndham Street) past the drill shed toward the underpass. A note on the back of the photograph states, "Toronto Regiment (3rd Battalion C.E.F.). Bugle band in front, Regimental band & soldiers following." No doubt the formation included many veterans of the Great War. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.52.25.)

The Guelph police also came in for criticism. They had made laid no charges during the entire week, which the Mercury took as evidence that the event passed largely without incident. The columnist for the Acton Free Press averred that it was due to overindulgence.

Another feature of Old Home Week were airplane rides. Recall that, in her postcard to her aunt, Mrs. Melvin Wolfe, Edith mentions taking a ride in an airplane. Airplane rides were not in the official program of the Old Home Week. Instead, they seem to have been the idea of Jack V. Elliott, the owner of the Jack V. Elliott Air Service based in Hamilton. Starting in 1922, Elliott had purchased and refurbished aircraft from the Great War for various commercial purposes, such as exhibitions and stunting.

(Jack V. Elliott depicted alongside what appears to be a Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny". Courtesy of the Hamilton Spectator, 12 November 1926.)Pilots soon took Elliott's planes barnstorming to various events. For example, Captian Smith and Mr. Gilles appeared at the Kitchener Old Home Week in 1925, flying "Nose dives, tail spins, loop the loop, rolls and other thrilling evolutions," not to mention a demonstration of wing walking! (Daily Record, 7 August 1925). Over the event, three Elliott planes took 236 passengers up for flights (Hamilton Spectator, 13 August 1925). At around $5 a flight, that quickly adds up.

("Carlstrom in a [Curtiss JN4] aeroplane at Long Branch [Toronto]," 25 November 1915. Victor Carlstrom was the pilot who flew a Blériot from Exhibition Park during Old Home Week 1913, the first plane to take off in Guelph. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, 3390042.)Of course, aviation was a somewhat risky endeavor in that era. Indeed, because of the absence of the contemporary Guelph Mercury, we only learn of the presence of the Elliott Air Service at Guelph during the Centennial because there was a crash. From the St. Catherines Standard (5 August), we hear that an Elliott plane, piloted by Dick Preston of Hamilton and bearing Bert Shier of Guelph, crashed through a fence on take-off and smashed to the ground. The plane, likely a Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny," was wrecked apart from the motor, which seemed salvageable. Happily neither pilot nor passenger were seriously injured.

From the report, we learn that the plane was using the "Karn farm" on the north outskirts of town as an airfield. I suspect that this is the property of John Karn, a Guelphite listed as a farmer and having a sand & gravel business located on the north side of Speedvale avenue, around the intersection with Delhi street. Interestingly, there was a plane crash at the same location on 8 October 1935, when a deHaviland Moth was attempting to land there (Brantford Expositor). It was in town to provide plane rides over the Royal City. From these reports, it seems that the Karn farm served Guelph as an occasional airstrip in the pre World War II era.

("Float from the Post Office, Guelph Centennial Parade." A sign on the side of float states, "The Post Office Serves the World," thus explaining the globe on the back of the float. Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 2009.52.23.)One hopes that Edith enjoyed her ride. In 1930, she married James Robinson. Her marriage certificate notes that, at that time, she was employed as a waitress at the Vimy Ridge Farm. (The farm was a training facility for British Home Children, boys exported from Britain to provide labour on Canadian farms. The program was discontinued the next year due to the financial strains of the Great Depression.) Mrs. Robinson moved to Toronto and remained there for the rest of her days.

("Guelph Centennial Old Home Week Sticker, 1927." Courtesy of Guelph Civic Museums, 1983.116.4.)The big event in 1927 was the apex of Old Home Weeks in the Royal City. Although the tradition persisted in some other Canadian towns and cities, Guelph never held another. There was "Guelph Days," a grand three-day hoopla held in 1932 of a similar nature but scaled down to fit with the circumstances of the Great Depression. Not quite the same. Of course, Guelph's Bicenntenial will be upon us in a couple of years. It will be interesting to see how it compares and contrasts with Guelph's previous wingdings such as the Old Home Week of 1927.